Dom Cooper speaks on trust, mistrust and distrust and what the three terms can tell us about an employee’s frame of mind and in turn, an organisation’s safety culture…

Trust appears to be a key factor in Occupational Safety & Health (OSH). Trust is the underpinning construct for both psychological safety and a just culture, and forms part of the British HSE’s ubiquitous 1993 definition of a ‘culture of safety’: communications founded on mutual trust, a definition which also very much applies to OSH information in the public domain.

To have trust implies a ‘leap of faith’ that people and/or entities are good, sincere and honest, or that something is true, correct and can be relied upon.

The opposite, distrust, refers to being proactively suspicious or doubtful of the honesty of entities and people, or the reliability of things.

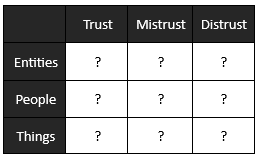

Somewhere in the middle, there is mistrust: a nagging suspicion or gut feeling that not everything in the garden is rosy, but you can’t quite put your finger on why. All three can usefully co-exist. For example, quality control processes and management system auditing are easily recognisable and acceptable displays of organisational mistrust or distrust that ultimately inspire greater trust in an entity’s products, services or systems. As the Trust Matrix tries to make plain, the targets of our trust can be entities (our organisations), people (our colleagues) or things (systems, equipment, etc.).

Figure 1: Trust Matrix

Formation of trust, mistrust and distrust

Trust is a mechanism we use to help us reduce the uncertainty associated with decision consequences. Trust in something or someone is constructed through a series of small ‘testing’ steps that we use to assess whether or not expectations are met.

The more they are met, the more our trust and confidence are built and maintained. Trust, therefore, anticipates a certainty of outcome (a reliance on people, entities or things performing as expected). Mistrust reflects doubt or scepticism which anticipates some unexpected, unknown dangers or discomfort. Distrust reflects a proactive anticipation of uncertain outcomes, which in turn, leads to a greater reliance on self[i].

Thus, the trust-mistrust-distrust continuum represents a personal risk control scale in which we increasingly rely on ourselves as we move from trust to mistrust to distrust. Moving from distrust to mistrust to trust means we are more open to relying on other people or things to meet our expectations.

Effects on workplace safety

The extant academic literature shows that ‘trust’ is associated with how we react to our co-workers and leadership[ii]. High trust in our co-workers buffers against incident involvement and helps ensure safety compliance via group norms[iii]. Similarly, high trust in management increases employees’ engagement in safety behaviours[iv] and reduces rates of accidents[v]; low trust in leadership leads to a marginal influence on employee behaviour. Equally, excessive trust in safety can reduce people’s personal responsibility for safety, which simultaneously increases their vulnerability to accidents[vi].

The extant academic literature shows that ‘trust’ is associated with how we react to our co-workers and leadership[ii]. High trust in our co-workers buffers against incident involvement and helps ensure safety compliance via group norms[iii]. Similarly, high trust in management increases employees’ engagement in safety behaviours[iv] and reduces rates of accidents[v]; low trust in leadership leads to a marginal influence on employee behaviour. Equally, excessive trust in safety can reduce people’s personal responsibility for safety, which simultaneously increases their vulnerability to accidents[vi].

Mistrust is associated with low safety performance[vii], low-incident reporting[viii] and increased litigation[ix]. A deep-seated mistrust of management by workers[x] detrimentally influences their safety behaviour[xi].

Conversely, creative mistrust (a healthy scepticism) of an entity’s risk control system can fulfil a beneficial role as people try to anticipate new problems, or old problems in new guises, arising from a heightened preoccupation with potential failure[xii].

Distrust can arise from an entity’s history of numerous workplace injuries, which in turn, is associated with additional distrust in management[xiii]. This can be further exacerbated by a blame game resulting from poor incident investigations that deny the organisation and/or its leadership may be at fault. On the other hand, initial distrust of new employees in high-risk industries (e.g., forestry) until they have proven they work safely is a risk control in and of itself[xiv], with distrust shown to be a better predictor of safety performance compared to trust[xv].

Lessons learned

Trust, mistrust and distrust are distinctly different, but related, constructs, that serve as personal risk controls. Each appears to have both beneficial and detrimental effects. How people react to leadership appears to depend on the trust their followers have in them: high trust equates to high employee engagement and performance, accompanied by lower levels of adverse events. Low trust is associated with the opposite, although too much trust can also lead to adverse effects. While mistrust and distrust may possess negative connotations, they both serve a useful function of helping people maintain a healthy scepticism of the status of safety in their sphere of operations.

With a complex pattern of positive and negative outcomes, it appears important for OSH professionals to understand how their entity is fostering trust, mistrust and distrust in relation to [1] the organisation’s overall prioritisation and approach to safety; [2] the interpersonal relationships of the people who work within it; and [3] the safety of ‘things’ (systems, equipment, processes and procedures).

In the words of Jon Osborne, Health, Safety and Environment Department at PD Ports, “there has to be a balance between respectful distrust, respectful mistrust, and open trust. A happy medium. Anything else suggests dysfunction”.

References

[i] McKnight, D. H., & Chervany, N. (2001). While trust is cool and collected, distrust is fiery and frenzied: A model of distrust concepts.

[ii] Luria, G. (2010). The social aspects of safety management: Trust and safety climate. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 42(4), 1288-1295.

[iii] Tharaldsen, J. E., Mearns, K. J., & Knudsen, K. (2010). Perspectives on safety: The impact of group membership, work factors and trust on safety performance in UK and Norwegian drilling company employees. Safety Science, 48(8), 1062-1072.

[iv] Conchie, S. M., & Donald, I. J. (2009). The moderating role of safety-specific trust in the relation between safety-specific leadership and safety citizenship behaviors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14, 137–147

[v] Zacharatos, A., Barling, J., & Iverson, R. D. (2005). High-performance work systems and occupational safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 77.

[vi] Jeffcott, S., Pidgeon, N., Weyman, A., & Walls, J. (2006). Risk, trust, and safety culture in UK train operating companies. Risk Analysis, 26(5), 1105-1121.

[vii] Gunningham, N., & Sinclair, D. (2011). A cluster of mistrust: safety in the mining industry. Journal of Industrial Relations, 53(4), 450-466.

[viii] Cox, S., Jones, B., & Collinson, D. (2006). Trust relations in high‐reliability organizations. Risk Analysis, 26(5), 1123-1138.

[ix] Furedi, F. (1999). Courting mistrust. The hidden growth of a culture of litigation in Britain.

[x] Levenstein, C., & Rosenberg, B. (2012). Creative mistrust. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy, 22(3), 283-296.

[xi] Conchie, S. M., Taylor, P. J., & Charlton, A. (2011). Trust and distrust in safety leadership: mirror reflections? Safety Science, 49(8-9), 1208-1214.

[xii] Hale, A. (2000). Editorial: Cultures confusions. Safety Science, 34, 1–14.

[xiii] Barling, J., Kelloway, E. K., & Iverson, R. D. (2003). Accidental outcomes: Attitudinal consequences of workplace injuries. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8(1), 74.

[xiv] Burt, C. D., Chmiel, N., & Hayes, P. (2009). Implications of turnover and trust for safety attitudes and behaviour in work teams. Safety Science, 47(7), 1002-1006.

[xv] Conchie, S. M., & Donald, I. J. (2006). The role of distrust in offshore safety performance. Risk Analysis, 26(5), 1151-1159.

The Safety Conversation Podcast: Listen now!

The Safety Conversation with SHP (previously the Safety and Health Podcast) aims to bring you the latest news, insights and legislation updates in the form of interviews, discussions and panel debates from leading figures within the profession.

Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts, subscribe and join the conversation today!

The extant academic literature shows that ‘trust’ is associated with how we react to our co-workers and leadership[ii]. High trust in our co-workers buffers against incident involvement and helps ensure safety compliance via group norms[iii]. Similarly, high trust in management increases employees’ engagement in safety behaviours[iv] and reduces rates of accidents[v]; low trust in leadership leads to a marginal influence on employee behaviour. Equally, excessive trust in safety can reduce people’s personal responsibility for safety, which simultaneously increases their vulnerability to accidents[vi].

The extant academic literature shows that ‘trust’ is associated with how we react to our co-workers and leadership[ii]. High trust in our co-workers buffers against incident involvement and helps ensure safety compliance via group norms[iii]. Similarly, high trust in management increases employees’ engagement in safety behaviours[iv] and reduces rates of accidents[v]; low trust in leadership leads to a marginal influence on employee behaviour. Equally, excessive trust in safety can reduce people’s personal responsibility for safety, which simultaneously increases their vulnerability to accidents[vi].