SHP hears from Dominic Cooper on psychological safety, its relation to OSH and lessons to learn from the term…

Like many on LinkedIn, I often see waves of posts on a particular topic from those seeking to sell a concept, service or product. Psychological safety (PS) is one of those topics: It is often promoted as some type of magic wand that brings about higher levels of performance, happiness, creativity, resilience, inclusion, equity, fairness, transparency and learning, as well as lower levels of conflict.

Apparently, without PS, organisations are inviting ‘poor-being’ (as opposed to well-being), stressed and burnt-out employees, high staff turnover and diminishing overall performance. Naysayers and sceptics are usually castigated or emotionally blackmailed into accepting and embracing it, with the irony being lost on those who engage in such practices.

What is psychological safety?

With its roots in 1960s research on organisational change, the PS construct currently refers to ‘a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking’. The term is meant to convey a sense of confidence that a work team won’t embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up (e.g., about safety).

In essence, PS is simply about trust during interpersonal communications. Dr. Amy Edmundson, who popularised the construct, states that trust and PS are closely related, but differ due to their object targets; PS is about us trusting others to give us the benefit of the doubt, as opposed to trust being about us giving others the benefit of doubt[i].

This perspective speaks to an external versus internal locus of control (outside-in vs. inside-out view), in that PS is always in the hands of others and is something being directed at, or done to, us.

Precursors to psychological safety

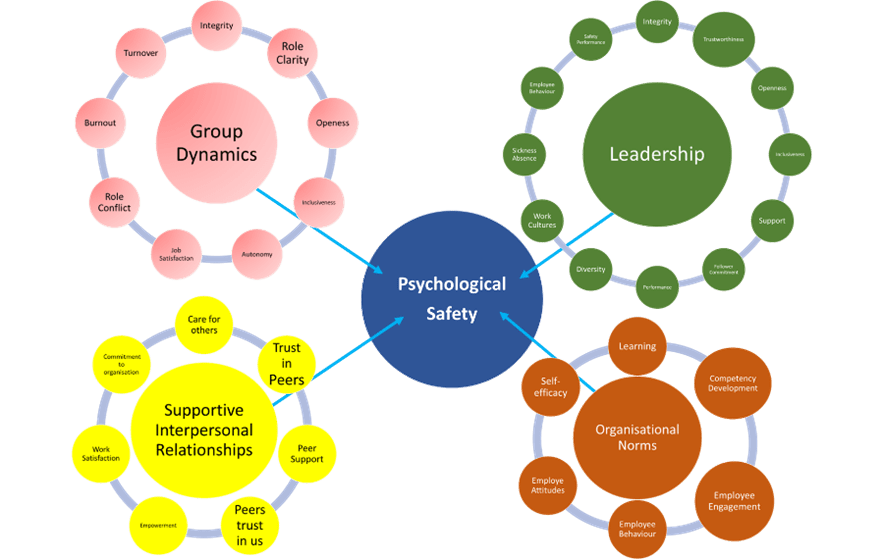

Figure 1: Precursors for psychological safety (and a host of other constructs)

The precursors for creating a ‘psychologically safe’ environment include supportive interpersonal relationships, group dynamics, leadership and organisational norms (culture).

However, a literature search reveals that these exact precursors are also precursors for a host of other work-related issues, as illustrated by the small ‘balls’ on the outer rings in figure 1. This begs the question: How do we know that any purported PS impact is due to PS rather than some other variable such as leadership, job satisfaction or organisational commitment?[ii] The answer is, we don’t.

Relationship of psychological safety to OSH

In the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) world, PS tends to be associated with the presence (or lack) of a blame culture which leads to reduced incident reporting, which then hinders learning, which subsequently holds back efforts to improve safety. Given the extent to which PS is being promoted in the OSH field as a panacea, what are its known relationships to OSH error reporting and injury reduction?

In terms of error reporting, evidence of impact is ambiguous: One US hospital study showed no difference in error reporting between high and low PS units[iii], while another showed that, despite PS levels staying the same over a one-year period[iv], error reporting significantly decreased over the second 6-month period. A further healthcare study showed the severity of a potential incident (near-miss) dictated the likelihood of it being reported: the more severe, the higher the likelihood[v].

Trust was found to be positively related to error reporting, while higher PS led to less reporting, which the authors speculated was because trust encourages the formal reporting of medical errors whereas PS encourages learning from mistakes[vi]. In OSH, when employees ‘trust’ their leadership it leads to desired behaviour; where there is low or no trust the influence of leadership on employee behaviour is marginal[vii].

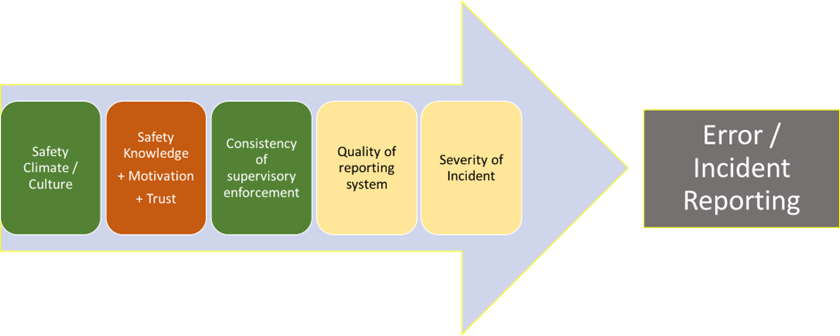

Figure 2: Factors known to influence error/incident reporting

The healthcare evidence shows that high PS does not have a uniform impact on incident or error reporting, as postulated by many, even in similar settings or with the same teams. Thus, trust seems more pertinent to incident reporting.

However, regardless of PS, trust or leadership[viii], error or incident reporting is likely moderated by the quality of the available reporting system[ix].

A recent Oil & Gas study supports this supposition, with the development of a generative voluntary safety reporting culture (GVSRC) fostering proactive reporting of hazards, near-misses, potential violations and operational errors that are precursors of accidents.[x] In terms of injury reduction, we know that ‘PS climate’ has a weaker and negligible relationship to OSHA-reported incidents compared to group ‘safety climate’ per se[xi].

Lessons learned

PS has the same precursors as many other common psychological factors, such as job satisfaction and organisational commitment. This muddies the waters when it comes to attributing outcomes to PS. The results of a representative sample of PS studies in healthcare show there is no consistent impact on increased error reporting, even in similar settings.

It seems that the prevailing safety climate, safety knowledge, safety motivation, trust, consistency of supervisory safety enforcement, quality of the error/incident reporting systems and severity of the potential impact of an error are far more relevant than PS per se. Such evidence indicates that the de facto PS construct is redundant, but time will tell.

Perhaps that’s why even Dr. Amy Edmundson admits PS is more magic than science[xii].

References

[i] Edmondson, A. C. (2004). Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. In RM Kramer & KS Cook (Eds.), Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches (239–272). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

[ii] Singh, B., & Winkel, D. E. (2012). Racial differences in helping behaviors: The role of respect, safety, and identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 106, 467-477.

[iii] Gilmartin, H. M., Langner, P., Gokhale, M., Osatuke, K., Hasselbeck, R., Maddox, T. M., & Battaglia, C. (2018). Relationship between psychological safety and reporting nonadherence to a safety checklist. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 33(1), 53-60.

[iv] Ridley, C. H., Al-Hammadi, N., Maniar, et al., (2021). Building a collaborative culture: focus on psychological safety and error reporting. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 111(2), 683-689.

[v][v] Jung, O. S., Kundu, P., Edmondson, A. C., Hegde, J., Agazaryan, N., Steinberg, M., & Raldow, A. (2021). Resilience vs. vulnerability: Psychological safety and reporting of near misses with varying proximity to harm in radiation oncology. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 47(1), 15-22.

[vi] Brimhall, K. C., Tsai, C. Y., Eckardt, R., Dionne, S., Yang, B., & Sharp, A. (2023). The effects of leadership for self-worth, inclusion, trust, and psychological safety on medical error reporting. Health Care Management Review, 48(2), 120-129.

[vii] Conchie, S. M., & Donald, I. J. (2009). The moderating role of safety-specific trust on the relation between safety-specific leadership and safety citizenship behaviors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(2), 137.

[viii] Probst, T. M., & Estrada, A. X. (2010). Accident under-reporting among employees: Testing the moderating influence of psychological safety climate and supervisor enforcement of safety practices. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 42(5), 1438-1444.

[ix] Macrae, C. (2016). The problem with incident reporting. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(2), 71-75.

[x] Adjekum, D. K., Afari, S. A., Owusu-Amponsah, N. Y., et al., (2023). Development of a generative voluntary safety reporting culture (GVSRC) model for the Gulf of Mexico (GOM) oil and gas (O & G) sector using attributes of the aviation safety action program (ASAP). Safety Science, 161, 106073.

[xi] Christian, M. S., Bradley, J. C., Wallace, J. C., & Burke, M. J. (2009). Workplace safety: a meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1103.

[xii] Gallo, A. (2023). What Is Psychological Safety? Harvard Business Review.

The Safety Conversation Podcast: Listen now!

The Safety Conversation with SHP (previously the Safety and Health Podcast) aims to bring you the latest news, insights and legislation updates in the form of interviews, discussions and panel debates from leading figures within the profession.

Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts, subscribe and join the conversation today!

An insightful read. I am always interested in reading about psychological and behavioural safety and leadership and how that relates to the workplace and beyond. The more you read and learn about these areas the more you start to realise how influential behaviours, deliberate or otherwise, can impact those around you and then you can start to use that to your advantage to get the behaviours you need from others. Currently reading Predictably Irrational which is in the realms of behavioural economics but highly interesting if anyone likes that sort of thing!

For me Dom it’s just a label for a sub set of general excellence. But if it helps management listen to the workforce knowledge and help those workers ask for help when they need it … can’t be a bad thing. (As usual nothing new here – like the elite forces conversation: ‘I need someone to tell me why this is a bad idea’ … ‘but we all think it’s a good idea’ … ‘that’s what’s i’m worried about’).

Maybe that’s why DSE operators, unlike those in the USA, are so frightened of disclosing ongoing Product Safety issues highlighted in the HSE Better Display Screen RR 561 2007? https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr561.pdf Perhaps the american operators felt safer making their ADA claims working from home after COVID struck as claims jumped from ‘5’ a week in 2017 to 2,500 a week in 2020! With DSE operators carrying-on regardless of self-harming presenteeism over the last couple of decades resulting in an average 20% loss in performance / productivity, increased error rates, mishaps even accidents, it’s about time work-stress-fatigue was addressed as, 2018 saw… Read more »