Support: Good manual handling techniques should be under constant review, with the option of refresher courses and additional training if needed. Pristine Condition offer continuous support for their clients, and this support should be maintained within the workplace.References:Note: over 40 references are stated below, some are linked together.

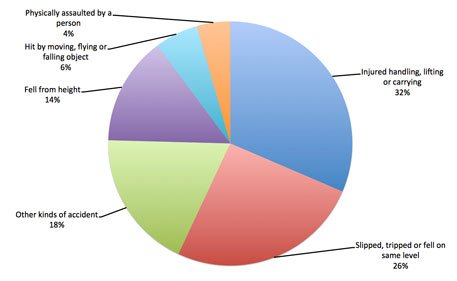

1. HSE (2013). Handling injuries in Great Britain, 2013. [online]. Available from http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causinj/handling-injuries.pdf p.3

2. HSE (2013). Table INJKIND2 – 2012/13. [online]. Available from www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/lfs/injkind2.xls

3. HSE (2013). Handling injuries in Great Britain, 2013. [online]. Available from http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causinj/handling-injuries.pdf p.3

4. Great Britain (1992). Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992 ; Statutory Instruments 1992 no. 2793. Available from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1992/2793/made

5. HSE (2004). Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992 Guidance on Regulations L23, 3rd Edition [online]. Available from http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/books/l23.htm p44-46.

6. HSE (2006). INDG143: Getting to grips with manual handling. [online]. Available from http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg143.pdf p6.

7. Graveling R, Melrose AS, Hanson, MA (2003). The principles of good manual handling: Achieving a consensus. Edinburgh, Institute of Occupational Medicine. [online]. Available from http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr097.pdf p1.

8. Graveling R, Melrose AS, Hanson MA (2003). The principles of good manual handling: Achieving a consensus. Edinburgh, Institute of Occupational Medicine. [online]. Available from http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr097.pdf p46.

9. Adams N, Dolan P (2002). Biomechanics of back pain, in Polak, F. (2011) Mechanics of human Injury, in Smith, Jacqui, (ed) (2011) The Guide to Handling of People (6th edn), BackCare, p60.

10. Astutis (2011) NEBOSH National General Certificate in Occupational Health and Safety: Unit NGC2: Volume 1, Cardiff, Astutis.

Hughes P, Ferret E (2011). Introduction to Health and Safety at Work, 5th edn, Oxford, Taylor and Francis.

Hughes P, Ferret E (2011). Introduction to Health in Construction, 4th edn, Oxford, Taylor and Francis.

Hughes P, Ferret E (2013). International Health and Safety at Work, 2nd edn, Oxford, Taylor and Francis.

11. Corner (2008). Health and Safety, Surry, Wolters Kluwer.

Duncan et al (2003). Health and Safety at Work Essentials, London, UK, Law Pack Publishing Limited.

Lexis Nexis (2010) Tolley’s Health and Safety at Work Handbook, London, Lexis Nexis.

McGuinness et al (2004). The Health and Safety Handbook, London, Spiro Press.

NEBOSH (2010) The NEBOSH Award in Health and Safety at Work, Leicester: NEBOSH.

Nesham et al (2012). NEBOSH Award in Health and Safety at Work, Unit HSW1, London, Rapid Results College.

Ridley, Channing (2008). Safety at Work, Oxford, Elsevier.

12. IOSH (date unknown). Managing Safely: your Workbook, version 3, Leicester, IOSH.

IOSH (date unknown). Working Safely: your Workbook, version 3, Leicester, IOSH.

13. CIEH (2008) Principles of Manual Handling. Principles of Manual Handling, London, CIEH.

14. Stranks (2009). Health and Safety at Work: An Essential Guide for Managers, 8th edn, London, Kogan Page Limited.

McKeown, C, Twiss M (2004). Workplace ergonomics a practical guide, Leicester, IOSH.

15. Coombes, I. (2010) A Study Book for the NEBOSH National Diploma: Hazardous Agents in the Work Place. 6th edn, Stourbridge, RMS Publishing Ltd.

Coombes I (2011). A Study Book for the NEBOSH General Certificate: Essential Health and Safety Guide. 6th edn, Stourbridge, RMS Publishing Ltd.

Deveux (2008). Health and Safety for Managers Supervisors and Safety Representatives, CIEH, London.

ECITB (no date). Work Safety Handbook, Hertfordshire, CCSNG.

Fellows et al (2011). Level 2 Health & Safety Made Easy, Qualsafe.

Ferret E (2012). Health and Safety Revision Guide, 2nd edn, Oxon, Taylor and Francis.

Hartley (2003). Heath and Safety: Hazardous Agents, Leicester, IOSH.

Phelstead J (2012a). NEBOSH Certificate, NGC2, London, Rapid Results College.

Phelstead J (2012b). NEBOSH National Diploma, Unit B Vol. 2, London, Rapid Results College.

Springer (2011). Health and Safety Handbook (Level 2), Doncaster, Highfield Ltd.

16. Leeson (2004). Health and Safety Handbook, Chadwick House Group.

Leeson, revised by Bryant (2006). Health and Safety First Principles, 2nd edn (revised by: Bryant, D.), London, CIEH.

17. Wordsworth (2010). Safe Manual Handling Handbook (Level 2), Highfield, Doncaster.

18. Graveling R, Melrose AS, Hanson MA (2003). The principles of good manual handling: Achieving a consensus. Edinburgh, Institute of Occupational Medicine. [online]. Available from http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr097.pdf

19. HSE (2004). Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992 Guidance on Regulations L23, 3rd Edition [online]. Available from http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/books/l23.htm p40.

20. Anderson CK, Chaffin DB (1986). ‘A biomechanical evaluation of five lifting techniques’, Applied Ergonomics Vol. 17, Issue 1, p2-8.

21. HSE (2013). Handling injuries in Great Britain, 2013. [online]. Available from http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causinj/handling-injuries.pdf p.4

Jonathan Backhouse is a chartered safety and health practitioner. The author can be contacted at [email protected]

This piece raises some interesting questions that as Wayne says needs addressing.

There is much conflict in methodology between such bodies as the HSE, CIEH and ROSPA. Many who focus solely on the back and not the whole body.

I think this is another piece of legisaltion that needs serious review. I note that the references in general relate to UK authors and publishers, I wonder how much conflicting information is based within the EU?

The more I read about changing advice about MH, the angrier and frustrated I get. How many people in real life, whether at work or doing gardening, household maintenance etc. have the time to take every facet of the advice and guidance given? Workplaces are locations where getting the job done is what is required and taking an inordinate amount of time to do everything written in MH guidance is impractical. I know of no-one who regularly lifts boxes of A4 paper from ground level, yet it is always dragged up when people talk about MH activities. Try getting into… Read more »

[…] mistake (i.e. bending with your back straight) with regards to correct lifting techniques for manual handling, is often […]