Approximately one-third of the UK workforce is over the age of 50, pushing the average retirement age beyond 65. Former HSE Employment Medical Adviser and Consultant Physician, Dr Chris Ide, lays out some of the key physiological issues for employers to be aware of in an aging workforce.

Benjamin Franklin once famously opined that the only two certainties in life were death and taxes. For most of us, death will be preceded by a variable period of senescence, during which our physical and mental faculties decline, although the rate at which this happens can vary strikingly, both within and between individuals. For example, Stanley Matthews was still playing first-class football aged 50 plus.

Aspects of physical prowess that can be easily measured, such as lung function, handgrip strength, and stamina (as measured by oxygen uptake) tend to peal in the third decade, but the Grim Reaper taps us on the shoulder at an even earlier age – the lowest death rates occur in children of school age but start to rise remorselessly from the mid-teen years onwards.[1]

For most of human history, the concept of a retirement age – when people formally cease working – has been non-existent. In societies that revolve around subsistence agriculture children joined the workforce, and over the years grew into various jobs and continued working until they were physically unable to continue. This practice continued into the early years of the industrial revolution, to the even greater detriment of child health. In fact, much of the earliest health and safety legislation, such as the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act (1801), and the Factories Act (1833) was passed in order to protect the health of young people by limiting the hours and places where they could work.

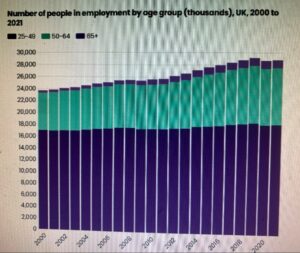

Figure 1: UK employment numbers taken from: Work – The State of Aging 2022. Centre for Aging Better [email protected]. Data compiled from ONS Labour Force Survey

UK workforce

The UK workforce is aging – roughly one-third are now over 50 years old, and the number of workers who are continuing to work beyond what used to be considered the traditional male retirement age of 65 has been increasing over the past couple of decades – see Figure 1 opposite.

There are a number of drivers behind this longer-term trend. Firstly, the replacement labour force simply isn’t there in the numbers required. The 16 – 24-year-old age group comprised 10.9% of the UK population in 1998, and by 2028, will have shrunk very slighty to 10.7% [2]The post-war baby boom (of which your author was a product) had petered out by the late 1960s and since 1974, the fertility rate for British women (the number of children born during a woman’s reproductive life span) has remained resolutely below 2, and for some years has been around 1.75 [3]. Furthermore, the arrival of many in the active labour market will be delayed by their being in full-time education, the numbers practically doubling to 1.87 million between 1992 and 2016[4].

The demise of Final Salary pension schemes, and their replacement by generally less generous Defined Contribution schemes introduces another factor from the employee’s point of view – the need to maintain what they perceive to be an adequate income. Finally, work is often enjoyable, providing a routine, a purpose in life and collegial support.

As mentioned earlier, the aging process carries an undisputed decline in physical and mental prowess. However, from a pragmatic point of view, they are probably less alarming than might be initially thought, since older workers can often draw on experience, knowledge, and enthusiasm to compensate for and maintain performance. However, recovery from illness and injury may be more protracted in older workers, so there is a challenge to occupational health and safety staff in order to ensure that the older worker is not disproportionately exposed to hazard from, and ultimately risk in, the working environment.

Loss of strength

Both men and women will lose about one third of their muscle bulk over the fifty years between age 30 and 80. Since women generally have less muscle mass at the outset, then the effect is more marked for them. When the effects of this are compounded by increased stiffness in joints, this can increase the liability to fail to speedily recover the upright position when tripping or stumbling, and a more damaging fall may result. Other contributing factors include changes in those nerve fibres which originate in the joints and inner ear and feed their impulses into those parts of the brain which help maintain our desired posture.

Another very important contributor to stamina is heart and lung function. The age-related fall-off in function means that older workers may struggle to maintain sustained high rates of effort, and may need occasional breaks to recover. To some extent, this decline can be mitigated by maintaining a good level of general fitness throughout life, and particularly from middle age onwards. Pre-work ‘Warming-up’ exercises may also be beneficial. Where joint stiffness is the result of severe arthritis, then replacement, particularly of major joints like the knee and hip, can be transformative.

To some extent, the decline in fitness may be mitigated by making sure that manual handling training is up-to-date, and that appropriate aids and ergonomic adjustments are in place, and regularly reviewed.

Statue of Stanley Matthews outside the Britannia stadium in Stoke. Matthews would continue playing football into his fifties. CREDIT: Martin Beddall / Alamy Stock Photo

Sensory Impairment

There are a number of changes that take place in the eye as part of the normal aging process. The phenomenon of presbyopia occurs because, from the mid-40s onwards, the lens of the eye becomes stiffer, which makes it more difficult to focus on near objects. So we get reading glasses (or develop longer arms), The lens also becomes more crystalline, and this increases the tendency for light to be scattered around the inside of the eye. This can be an even greater problem if cataracts (opacities in the lens) develop, reducing the sharpness of vision. This scattering of light leads to problems with glare, particularly at night.

These changes may also have a subtle effect on colour perception, and the peripheral visual fields may also contract slightly. Thus it is important to counteract these problems by the provision of more intense light, and greater contrast. Come to think of it, diabetes can accelerate the appearance of cataracts, and damage the retina (the light-sensitive membrane at the back of the eye),. The chances of developing type 2 diabetes can be reduced by adopting a healthier lifestyle, and avoiding becoming overweight.

A number of common eye disorders are amenable to treatment. For example, cartaracts can be extracted and replaced with a plastic lens. This can often be done as a day case. Provided there are no other impediments to vision, sharpness of vision is greatly improved and return to work follows shortly afterward, although a longer convalescence may be required for those in hazardous or safety-critical work.

The deterioration of hearing as we age (presbyacusis) is well-established and can be more pronounced in those who have been exposed to excessive volumes of noise, both as a result of work and leisure activities. Typically, this affects the higher frequencies and is not hugely important in understanding speech, but if the loss starts to encroach on the middle frequencies, then problems may arise with appreciating consonants such as ‘d’, ‘p’ ‘f’ and ‘s’.

Other difficulties may occur in hearing conversation against background noise, and the phenomenon of recruitment, in which the cochlea – found in the inner ear, and is responsible for converting the sound pressure waves into electrical activity for the brain to analyse and interpret responses disproportionately – and sometimes painfully -to increases in volume. (Just think of the elderly relative who says, “Speak up, young man!”, and when the speaker does just that, says tetchily,“Now, there’s no need to shout!”). While hearing aids are of some use and are becoming increasingly sophisticated, they still have a tendency to non-selectively amplify all sound in the vicinity. An increased emphasis on visual warnings of hazards offers the best protection.

Shiftwork

Shiftworkers at an apple processing plant. Credit: Arno Senoner/Unsplash

Although thought of as a modern phenomenon, shiftwork has always been part of working life – the provision of morning rolls, newspapers, civil, military and maritime safety and security has required some people to work during the hours of darkness, and this became more common as the industrial revolution progressed, probably with the need to ensure maximum returns on investment, coupled with the inability to be able to start and stop processes. In 2017 slightly less than 20% of the UK working population was involved in some sort of shiftwork [5]. This is unnatural, since it involves the disruption of circadian rhythms, especially if it involves night shifts.

Most people can adapt to shiftwork – perhaps for economic reasons – but some manage it more easily than others, and the proportion who cannot, grows in size as the population ages, especially if they are starting shift work for the first time. This may have to do with the changes in sleep patterns that often affect older people. Another group who need special consideration are those who take medicines where the dosage is time-critical – for example, I’m thinking of those with diabetes who are using insulin, and need to inject around meal times, or anti-epileptic medication, or those using tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitryptiline, as part of a pain relief regime, where taking them just before bedtime helps to minimise the sedative side effects.

Another group of workers (of any age, for that matter) who might be best advised to stick to daylight-hours-only work, are those who suffer from epilepsy since sleep deprivation is a significant trigger factor for seizures. If daylight hours only working is not possible, then the best shift pattern is probably a rapidly rotating forward-progressing system.

Cognitive Impairment

This is probably the most dreaded consequence of aging. The most extreme form of impairment (dementia) is rare in the under 65s – less than on per cent, but from then on, it rises, and affects about one in five of those in their 80s (but note – the flip side of that statistic is that four out of five will not be affected!) There is a degree of cognitive decline which is inevitable. In part, this is due to older workers relying more on ‘Crystalline intelligence’ – drawing on past experience to solve problems, whereas they may be less able to use ‘Fluid intelligence’ which uses innovation and analysis to deal with problems from first principles.

Different learnng strategies may well be required for training and upskilling older workers, in particular, more time may be needed, but once the skill has been successfully imparted, then older workers will usually function just as well. Problems with memory – and in particular, short-term recollection can best be combatted by the use of writing lists, availability of notice boards abd electronic prompting devices.

In the late 1980s, the DIY chain B&Q decided to staff its Macclesfield branch solely with those over 50. A few years later, its performance was benchmarked against four comparable superstores. The Macclesfield branch had profits 39% higher, staff turnover was one-sixth, absenteeism was almost 40% less, and customer satisfaction was higher. Although some aspects of their 1980s recruiting policy would now be against the law, B&Q continues to encourage older people to enter, and remain in, its workforce.[6]

While Shakespeare had lots pf gloomy things to say about senescence, he also wrote ‘With love and laughter, let old wrinkles come.’[7] If we add to this “Provision of a safe and healthy working environment” then organisations may yet find a solution to their staffing problems, whilst providing a service that strikes a chord with their older customers, who may be comprising a sizable section of their client base.

By applying their established skills, workplace safety advisers can help to transform these visions into reality.

REFERENCES:-

- Death rate in the UK 2020 by age | Statista

- https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/ukpopulationpyramidinteractive/2020-01-08

- U.K. Fertility Rate 1950-2023 | MacroTrends

- How has the student population changed? – Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk)

- https://www.ons.gov.uk/search?q=shiftwork

- B&Q and Ageing Workers | The Society of Occupational Medicine (som.org.uk)

- William Shakespeare , Merchant of Venice Act 1 Scene 1.

What makes us susceptible to burnout?

In this episode of the Safety & Health Podcast, ‘Burnout, stress and being human’, Heather Beach is joined by Stacy Thomson to discuss burnout, perfectionism and how to deal with burnout as an individual, as management and as an organisation.

We provide an insight on how to tackle burnout and why mental health is such a taboo subject, particularly in the workplace.