SHP speaks to Sarah Waters, Professor of French Studies at the University of Leeds, who has recently published a report, with Hilda Palmer from Hazards Campaign, looking into 12 suicide cases that occurred between 2015 and 2020 to discover whether they could be attributed to the workplace.

Professor Waters is a specialist on French labour and the French workplace. In around 2010, the French media were reporting on waves of suicide that were taking place in different companies, most notably France Telecom. Prof Waters admitted being ‘completely taken aback’ and ‘shocked’ by the news. “My research had always shown that work is the space that brings people into society, gives them stability and gives them a sense of identity, a sense of belonging. I just couldn’t understand why and how work and working conditions would get so bad that someone would want to take their own life.”

Professor Waters is a specialist on French labour and the French workplace. In around 2010, the French media were reporting on waves of suicide that were taking place in different companies, most notably France Telecom. Prof Waters admitted being ‘completely taken aback’ and ‘shocked’ by the news. “My research had always shown that work is the space that brings people into society, gives them stability and gives them a sense of identity, a sense of belonging. I just couldn’t understand why and how work and working conditions would get so bad that someone would want to take their own life.”

This, Prof Waters said, was the driving force behind her research into work-related suicides. She has published a book on French workplace suicides and has been working closely with the Hazards team, which has been leading a campaign in the UK on work-related suicide.

The latest report, Work-related suicide: a qualitative analysis of recent cases with recommendations for reform, which stems from a Research England-funded study into a selection of suicide cases, found that employee suicides are still largely treated as an individual mental health problem that has no direct relevance to work or the workplace. The report calls for work-related suicides to be monitored, regulated and prevented.

Prof Waters says: “The aim of the study was to look very closely at some of the work-related causal factors that might lead to suicide, and to look at some of the causal connections between suicide and work in the UK context. Unlike many other countries, in the UK suicide, even where there are clear links to work, is treated as an individual mental health problem. There tends to be a denial on the part of the HSE and other agencies that there is a link between suicide and work. So, our aim was to bring to light some of the causal factors that drive employees to suicide in the UK context.”

Scroll to the bottom of the page to listen, in full, to the interview with Professor Sarah Waters.

The study

The report builds on the work carried out by Rory O’Neil, from Hazards Magazine, Prof Waters and Hilda Palmer, from FACK and Hazards Campaign. The study looked at 12 individual suicide cases that had occurred between 2015 and 2020. “We basically looked at every single document, every single text, that had been written or produced in relation to each of those 12 suicide cases. We wanted to open them up to scrutiny, to look at the factors in detail. We carried out extensive interviews for each of the suicide cases, speaking to family members, colleagues, trade union reps, in an effort to push the research forward in the UK context and to give concrete evidence of the connections between suicide and work and show what some of those causal connections were in the small sample that we looked at,” Prof Waters continued.

What were the findings?

In all the cases that were selected, there was already work-related evidence and work-related factors had already been established by an official source, a coroner, an employer or a police investigation. “We knew there were work-related factors there, we wanted to look at what they were,” Prof Waters said.

“One prominent causal factor was workload, people burdened with so many different tasks, so many different roles, that they simply couldn’t cope and, as a result, were pushed into a situation of chronic overwork. They destabilised their lives and their mental health.”

This is a very well-known phenomenon in Japan, Prof Waters continued. “Japan has a very particular corporate culture and there’s a phenomenon called Karoshi, or suicide by overwork, where people literally work themselves to death. They end up working continuously and intensively and have a breakdown and take their own lives.”

The study found this to be an issue not just in Japan. “One of the factors we found is that this is prevalent more widely, particularly in the health sector, with people working very long and unpredictable hours. It means they struggle to construct a stable, personal life or a stable family life.”

The study also discovered several other factors. “We found documented evidence of workplace bullying in two of the cases we looked at, both of which involved young trainees, very tragically. We also found exposure to violence and trauma to be a factor. Within the emergency services, we looked at two cases of firefighters and a case of a police officer, all of whom had been exposed to trauma in the course of their work. The trauma had a catastrophic effect on their mental health and resulted in suicide in those three cases.”

Is overworking more of a factor now, than it was in the past?

“What really interested me about this is that, in historical terms, it appears to be a new social phenomenon. There’s something about changing conditions of work over the past 20 to 30 years which is causing people trauma, and which has resulted in a sharp rise in work-related suicides. There is evidence of this across the world, not just the UK, it’s an international phenomenon.

“If you go back to 19th century Britain where there were horrendous working conditions. Marx and Engels went into exhaustive detail about cushions in the factories and how they affected the health and the lives of workers. There’s hardly ever any mention of suicide in Marx’s three volumes of Capital. Suicide isn’t mentioned in Engels’ study, The Condition of the Working Class in England, published in 1845. In written material discussing conditions in the factories in working class England, suicide is barely mentioned.

“So, there is something about the present time, which is placing unprecedented pressure on people’s mental health. I do think it’s historically linked to the fact that far more pressure is placed on our mental health nowadays, it’s not just about our physical bodies or physical attributes. There’s a rise in precarious work, workers become more unstable, workers become more intense, digital work means we’re constantly switched on, we’re expected to work all the time. So, there’s a whole complex series of factors, which have placed huge pressures on mental health, which explain why work-related suicides are on the rise and why they’re on the rise now, at this particular moment in time.”

Suicide figures in UK working age men

Data suggests that males aged 45 to 49 years have the highest age-specific suicide rate (25.5 deaths per 100,000 males) in the UK. Prof Waters added her thoughts on why that was: “General suicide rates are rising in the UK at the moment anyway, and the highest rates are among the working age men. There was a very important study, produced by researchers at the University of Manchester earlier this year, called Suicide by middle-aged men, that look precisely at why middle-aged men have such high rates of suicide.”

The study collected data from a range of investigations into the deaths of men aged 40-54 by suicide (including probable suicide) in England, Scotland and Wales by official bodies, primarily coroner inquests (police death reports in Scotland). The subsequent report is based on deaths that occurred in a 12-month period between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2017 and describes the antecedents of suicide and barriers to accessing services, and includes recommendations for suicide prevention for men in mid-life.

“It found that a lot of the factors are socio-economic, things like the effects of unemployment, the effects of poor housing. Also, issues around mental health, substance abuse. Our criticism of that report is that it doesn’t look at work. We know the highest rates are amongst working age men, so why aren’t we looking at work? Why aren’t we looking at changing conditions at work? Why aren’t we looking at why work today is resulting in higher rates of suicide amongst working age men? That report studied a vast number of cases and 30% of their sample were unemployed at the time of death. But what about the other 70%?

“Most research on suicide is conducted by people, epidemiologists people working in public health people working in the medical sector, who are often reluctant to look at the socio-economic or the workplace factors that are relevant.”

Under-reporting of work-related suicide figures

The team behind the work-related suicide report have raised the issue with the HSE, and other public agencies, and say they have found considerable resistance in the UK to treat suicide as something that is work-related.

“There’s a persistent misconception that suicide isn’t something that’s work-related. In the HSE regulations, where they set out the range of work-related deaths that must be reported to them for further investigation, it specifically excludes suicide. Suicide is presumed to be a personal, individual, voluntary act. It’s presumed to stem from individual mental health, and not from work.

“What we’re trying to say is that this is dangerous, because it means that the conditions, practices or policies that have pushed one person to take their own life, remain unchanged. And there’s no obligation for an employer to do anything about them, to make any changes in the aftermath of a suicide. So, those conditions continue to persist for everyone else.

“Frustratingly, we’re finding that bringing about any change is extremely slow, and it’s cultural, because I think it’s not just a question of changing one piece of legislation, it’s about changing a whole cultural mindset that tends to relegate suicide, to the individual mental health sphere.

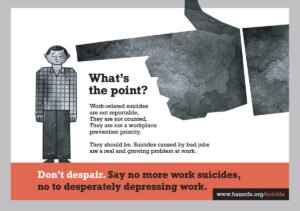

Click on the image to enlarge.

“If actions, such as including suicides in the list of work-related deaths, was implemented, it could prevent avoidable deaths from taking place. Our report showed precisely that avoidable suicide deaths are taking place because of a lack of reporting, a lack of regulation, and a lack of prevention.”

Hazards produced a campaign, which resulted in thousands of postcards being sent to HSE calling for it to change its approach to work-related suicides. It estimates that 10% of suicides may be work-related, so reports that the latest figure for the UK is 650. “One of the problems of course, is because the data isn’t collected, you’re in a negative cycle and people can assert that the problem doesn’t exist.

“In the United States, for example, every single suicide that takes place in the workplace is counted, and is part of an annual database, and that is standard practice in most countries. Because if you don’t collect data, you can’t see a problem.”

Recommendations

A key recommendation of the report is to include suicide in the list of work-related deaths that must be reported to the Health & Safety Executive for investigation. The report also calls for explicit and enforceable legal requirements that oblige employers to take responsibility for suicide prevention. It says that there is an urgent need to modernise health and safety regulations in order to prevent avoidable deaths and bring the UK in line with other industrialised countries where suicides are systematically monitored and treated as a serious public health concern.

“Our main recommendation,” Prof Waters concluded, “is for the HSE to include suicide in the list of work-related deaths that are recorded and monitored by RIDDOR and subject to further investigation. That really is the starting point for everything else. Until that is done, employers will continue to see suicide as something that concerns the individual and his or her family and not, not the workplace.

“We sent the report to the HSE, and we also sent it to the Chief Coroner. We had a series of recommendations for those different organisations. For the Chief Coroner one of our key requests was for more consistent use of preventing future death reports. They are rarely used and can be quite a powerful lever for changes in the workplace. We think that, as the regulator for health and safety standards in the UK workplace, it starts with them.”

HSE has ‘no plans to revise or amend the reporting requirements’

SHP asked HSE to comment on the report and some of the recommendations made by it. HSE gave the following statement…

‘The Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 2013 (RIDDOR) only requires fatalities to be reported if they are a result of a work-related accident (Reg 6(1)). Our policy position remains that for an occurrence to be considered as ‘work-related’ it must arise out of, or in connection with, work and that an ‘accident’ is an unforeseen and unintentional consequence of that work. As such, incidents of suicide and/or self-harm do not meet the reporting requirement under RIDDOR. HSE’S Incident Selection Criteria is based upon the definitions used within RIDDOR.

‘The Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 2013 (RIDDOR) only requires fatalities to be reported if they are a result of a work-related accident (Reg 6(1)). Our policy position remains that for an occurrence to be considered as ‘work-related’ it must arise out of, or in connection with, work and that an ‘accident’ is an unforeseen and unintentional consequence of that work. As such, incidents of suicide and/or self-harm do not meet the reporting requirement under RIDDOR. HSE’S Incident Selection Criteria is based upon the definitions used within RIDDOR.

‘A coroner can choose to draw HSE’s attention to a case of suicide that they consider the enforcing authority should be aware of. Additionally, where a person has committed suicide and there are concerns that this was as a result of their work then this can be raised directly with HSE as a concern, for example by the family or partner of the deceased. There are no plans at present to revise or amend the reporting requirements under the RIDDOR reporting regime.

‘HSE has developed lots of resources to help employers, irrespective of size or sector, to assess the risks of work-related stress and mental health to their staff and, where risks are identified, the employer must take steps to remove or manage them, as far as reasonably practicable. The independent Workplace Health Expert Committee (WHEC), who provide independent expert opinion to the HSE on workplace health, recently considered the occupational factors that may contribute to the risk of suicide HSE Workplace Health Expert Committee (WHEC) Report – Work-related suicide – WHEC 18 (2021). It identified there is evidence of variation in suicide risk between occupations. However, it went on to say that the determinants of this were complex, encompassing societal, cultural, and individual factors. The WHEC also found the evidence for a direct role of psychosocial work stressors on the risk of suicide was limited and somewhat inconsistent.

‘Suicide is a societal issue wider than the workplace, but there can be links to workplace factors. HSE promotes preventing work-related psychosocial risks to protect workers from potential injury. In addition, HSE continues to support broader cross-Government initiatives to prevent suicide and is reviewing the information currently contained on the Stress at work pages of the HSE website in relation to suicide, to provide additional text and links to resources and organisations that can provide specific guidance, help and support to employers and bereaved families. Those experiencing stress or a mental health problem should not be stigmatised.’

See Sarah talk about this subject as part of a Women in Health & Safety webinar.

Listen, in full, to the interview with Professor Sarah Waters…

The Safety Conversation Podcast: Listen now!

The Safety Conversation with SHP (previously the Safety and Health Podcast) aims to bring you the latest news, insights and legislation updates in the form of interviews, discussions and panel debates from leading figures within the profession.

Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts, subscribe and join the conversation today!

Professor Waters is a specialist on French labour and the French workplace. In around 2010, the

Professor Waters is a specialist on French labour and the French workplace. In around 2010, the

‘

‘

A really good article I fully support. We do need to change attitudes, as poor attitudes continue to contribute to the stigamtisation issue surrounding mental health. Additionally we need to remember that health is intrinsic, and ensure that good physical health remains as important as encouraging a healthy approach to poor mental health issues. You cannot have one without it affecting the other. As I learned The Health and Social Care Act of 2012 enshrined in law the parity of esteem for physical and psychological health to be treated equally.

This is an excellent article; kudos to the authors on a sensible and important perspective

From close personal involvement in two suicides, which included workplace causal factors, this is a valuable contribution to an important area, which we should all give serious consideration to, as employers, ‘health & safety professionals, colleagues and perhaps most importantly – friends. Learning from incidents is vital, effective learning from serious accidents difficult, learning from suicides is incredibly difficult. Moving health and safety into this vital new area (like our traditional ‘iceberg’) will improve many many peoples health and lives, as well as prevent suicides. To learn, as soon as possible, whilst avoiding causing increased harm to people closely associated… Read more »

With HSE reporting (2007) induced visual repetitive stress injuries accounting for 58% of DSE Operators vision loss with half of those suffering other MSD’s and the UK ONS not recording work-related deaths sure is time to monitor predictable occupational health risks.