SAFETY CULTURE

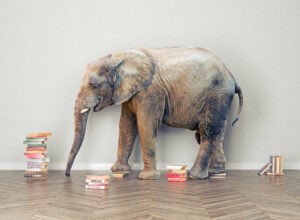

Elephant in the room? Reframing accountability

How can we view accountability as a positive experience rather than one of blame? Zoe Nation outlines a new approach.

CREDIT: Victor Zastolskiy/Alamy Stock Photo

Accountability is misunderstood and is often the elephant in the room when discussing innovative safety or proposing ideas for progressive investigation approaches. The initial responses I receive when suggesting people make mistakes and therefore blame fixes nothing, are along the lines of: “So we don’t have to take any responsibility for our actions then.”; “Now no one is accountable.”; “It’s a get out of jail free card.”; or cries of, ‘There will be anarchy!”.

Rather than getting into definitions and origins, it is more helpful to focus on the way accountability is used; the desire for it, and also some of the fear created in an operational context. This is how I try to help people think differently about it; maybe it will help when you have similar discussions.

Try starting with the understanding of the term by combining personal experience, ask: “Tell me what accountability looks like and feels like to you, in practical terms?” For example: I see someone not hooked on at the job site, or I interview someone following an incident where they consciously bypassed a safety device. How do I know if they feel accountable or not?

The answer is that we can tell from body language, we see them owning their actions with comments like: “I’m sorry, I feel terrible.”; “I let my team down.”; “I don’t know what I was thinking.”; “I should wear the punishment.”; “I’ve impacted my whole team.” The majority of the time this is what I hear when I speak to someone about following an event, mistake or rule breach.

Culpability and blame

Somewhere along the line, we have confused accountability with culpability and blame. If you replace accountability with responsibility or ownership it becomes a more positive experience. How do I allow someone to own their actions? I ask them to tell me what happened, I listen and I give them respect and time to share. I support them so they can share their account in a safe space. I must not judge and I aim to build trust. In doing this, I’m also learning about the reality of work, and what made sense at the time.

Yes, there will always be a small proportion of people who do not take immediate responsibility for their actions and even fewer who never do. However, I’m still curious about this group. I want to understand why they are unwilling to own their actions and be part of the solution. This could still tell me something about the system design. How are they being performance-managed during everyday work, long before the event? Have they received feedback about their behaviours and been given the chance to take accountability before? Are they fearful of owning up to this because they think they will be punished?

Remind them of the research: performance change is more significant following positive reinforcement than negative

Back to the room with the elephant. Once we have discussed the group’s experiences, with people feeling remorseful and we’ve established what accountability looks like, we can ask for a list of pros and cons of discipline. We’ll hear why they have used it previously and why they need it now. We can then discuss the concept that punishment tends to lead to avoidance of getting caught rather than stopping the behaviour itself. Think about how we flash each other to warn other drivers there is a speed camera ahead on the public roads, or perhaps when we use code to radio around when a leader or safety advisor arrives on site for a random inspection. Remind them of the research: performance change is more significant following positive reinforcement than negative. I ask if punishing is getting them closer or further away from being a learning organisation that can reduce repeat incidents.

Forward-looking accountability

Here is the major difference and how I believe you create a shared forward-looking accountability rather than backwardly looking to blame. After the person has told their story (their account), ask: “Okay, so how do we stop this from happening again?” They misht respond with, “Well I should be more careful.” Stop them and say, “So what do you want to do differently, but also, what do you need from us as an organisation? What would you need from your supervisor/client/manager/CEO to guarantee this doesn’t happen again.” This is how they truly become part of the solution, by being allowed to be accountable for their part in the event, with the recognition that they are not solely responsible because they are part of the system. Considering systems thinking, we know that the organisation had a role to play in the choices the person made at that time.

I have never heard, “There is nothing I would do differently’ when I ask this. The focus shifts to, “We will learn from this, and we can improve.” (we, not I).

Finally, discipline is still a valid leadership tool. This approach is not no discipline at all but you will require it less since the emphasis is on learning rather than blame. If you are concerned about consistency in application, then you can implement a Just Culture matrix. But typically, once implemented with the above philosophy, it is used less and less as we become more aligned and practiced in the approach. Involving Legal and HR early in this discussion is vital to understand how to integrate with existing processes and commitments.

Tips

In summary, here are some tips to help when having conversations around accountability, and how it is still achievable with a modern safety or systems thinking lens:

- Ask what accountability looks like in practice.

- Explain some ideas around what it is (ownership, accounting for one’s actions) and is not (blame, culpability).

- Ask about the pros and cons of punishment and if it enables a learning organisation.

- Satisfy the human need for accountability by getting the person to tell the story of what happened and then try to move forward by helping to solve it and stop it happening again.

- Propose that you don’t need punishment to get accountability.

- Discipline is still a tool, but you’ll find it is not usually needed with this approach. Just Culture models can help build structure and consistency, although in a mature organisation I tend to see it being phased out eventually.

Elephant in the room? Reframing accountability

How can we view accountability as a positive experience rather than one of blame? Zoe Nation outlines a new approach.

Zoe Nation

SHP - Health and Safety News, Legislation, PPE, CPD and Resources Related Topics

Safety Leadership: From virtual safety to real safety

Navigating turbulence: Boeing’s lessons in risk management

Verdantix Green Quadrant: EHS Software 2023

Excellent information, Zoë! I like how you illustrated that holding someone accountable for their actions does not necessarily mean they must be punished. Well done!