Martin Dean, Senior Manager, DuPont Sustainable Solutions explains why risk management coaching can be more effective than training.

Many organisations run training programmes to increase risk awareness among employees, improve safety standards and change engrained habits and behaviours that pose a threat to people, operations and the environment. But if staff follow the example of their leaders and these leaders are not able to carry the workforce with them on a joint safety improvement journey, then the effect of training is likely to be diluted. How can managers develop the skills they need to bring the organisation with them on a journey of continuous positive development?

Company boards, investors, employees and other stakeholders tend to have high expectations of senior managers. That creates a considerable amount of pressure that many managers have to deal with on their own, in private. Perhaps that is why so many of them look to coaching to give them the opportunity to discuss questions, doubts, goals and expectations with an objective, external professional. According to a 2013 Stanford University study “nearly two-thirds of CEOs do not receive outside leadership advice, but nearly all want it”[1]. Coaching is both a sign that the board considers the executive or manager worthy of investment and an opportunity for them to develop the skills they need to deliver the drive, strong guidance and decision making that is expected of them. But in view of shrinking budgets, many organisations wonder if the same result can’t be achieved through group training.

Training and Coaching – what is the difference?

Coaching can be defined as collaborative support for decision makers to enable them to achieve objectives, address issues, develop at a personal level and build the skills to guide their teams towards reaching key targets. Effective coaching should be a dialogue that allows coachees to unlock their potential and so add value to the organisation and the people they manage. Coaching should, in other words, enable them to achieve greater productivity, but with less stress. That sounds like an obvious win-win, but in order to work, coaching has to deliver in the long term. In his book Coaching for Performance, coaching guru John Whitmore writes, “Coaching for Performance is (…) a means of obtaining optimum performance – but one that demands fundamental changes in attitude, in leadership behaviour, and in organizational structure.” [2].

While coaching focuses on enabling people to achieve their full potential, training is concerned with transferring knowledge and skills and with prompting certain behaviours. It also tends to be more structured and fixated on a stated objective than on a personal target an individual wants to achieve.

What the research says

One of the largest executive coaching impact studies is one conducted in 2006 by Professor James W. Smither of La Salle University’s management department[3]. It evaluated 1202 senior managers over two consecutive years. Those senior managers who had worked with a coach all got more positive feedback from supervisors, peers, subordinates and independent researchers than those who hadn’t. They noted improvements particularly in goal setting, encouraging others to make improvement suggestions, and in achievements. Two more recent meta-analyses bear out these results. An analysis of executive coaching by the University of Amsterdam[4] in 2014 concluded that it was effective because of its positive impact on performance and skills of senior managers, as well as on their well-being, their ability to cope, work attitude and goal-directed self-regulation. A paper presented by Rebecca Jones, a senior lecturer in management at the University of Worcester, at a British psychology conference in 2014[5] furthermore reported that executive coaching has a greater impact on performance than other workplace development tools.

Who should have what form of coaching?

As all the research corroborates the effectiveness of coaching, many boards and senior decision-makers are keen to make use of it but face the difficult task of deciding who should have coaching and what form it should take.

While the Stanford University study reported that board directors said their executives needed to work primarily on “mentoring skills/developing internal talent” and “sharing leadership/delegation skills”, many organisations avoid coaching them as such soft, intangible skills are very nuanced and can be difficult to develop. That is why the market is moving away from more generalist coaches to specialists. The results of several international studies have shown that the success of coaching is influenced not only by the willingness of the learner to be coached and the relationship between the coaching partners, but also by the level of specialist knowledge of the coach.

Organisations that want to develop the soft skills for their managers should therefore be looking to coaches that focus on motivational and inspirational skills in order to enable leaders to build a more effective organisational culture of continuous improvement.

Measuring the effect of coaching

DuPont Sustainable Solutions (DSS) is an established operations and safety management consultancy that offers specialist risk management coaching as part of its DuPont Risk Factor programme. DSS helps senior executives and middle management boost soft skills with the coaching that the consulting firm has developed.

DuPont Sustainable Solutions (DSS) is an established operations and safety management consultancy that offers specialist risk management coaching as part of its DuPont Risk Factor programme. DSS helps senior executives and middle management boost soft skills with the coaching that the consulting firm has developed.

This form of coaching has proved itself at all management levels from CEO to shift leader and can be customised to different situations and areas of responsibility. As a result of such coaching, a leading German engineering company, for example, found its safety performance improved by 73%.

The DSS style of coaching not only focuses on soft skills but is designed to be scalable and measurable by carefully gauging capabilities and competencies at the beginning and end of each coaching journey.

It starts with a self-assessment which allows coachees to understand the emotional triggers and motivators that influence their decision-making and risk perception. This connects with other elements of the programme, which is based on the psychology of decision-making. The programme uses a variety of tools to help people own the fact that they take risks, choose safer options and change behaviours. The coaching goes a step further and uses an approach based on authenticity, understanding and storytelling to support business leaders and managers as they learn to inspire and influence transformation in their organisations. Frequently coaching will begin with an exploration of management routines and past experiences of unsafe situations. Coaching will help participants to understand the role of regular praise, new methods and tools, as well as fresh examples to keep employees motivated in identifying, anticipating and managing risk in different situations.

In this context, the coach acts as an external sounding board and sparring partner for managers, reviewing and furthering their insights and ability to act as role models in their organisation. Coaching also allows participants to define personal and business goals, discuss questions and areas where they may have difficulties. In partnership with the coach, they identify the experience, skills and tools they can use to make changes. The benefit of this coaching approach is that participants can apply the skills they learn to other areas far beyond the risk management field.

Developing leadership competencies

Coaching is one way of building and developing leadership competencies. Which leadership competencies are critical to move the organisation forward will depend on the cultural maturity of each company. In his book The Inner Game, Tim Gallwey developed an equation that takes into account internal hindrances such as fear, self-doubt, lapses in focus and limiting concepts of assumption that prevent individuals from achieving their best. The Inner Game equation – Performance = Potential minus Interference – provides a solution to overcoming these stumbling blocks. This equation also applies to organisations.

A company culture reliant on strict rules and regulations can act as a form of interference, in other words as a performance inhibitor. If employees instead have the chance to develop and act on their intrinsic motivation, they are more likely to take accountability for their actions and decisions and so develop their full potential.

To cite John Whitmore’s Coaching for Performance once more, “by enabling an interdependent culture, organizations can tap into the potential of every employee and change the very relationship between employees and organizations. This is the very cutting edge of coaching and organizational development.”

Conclusion

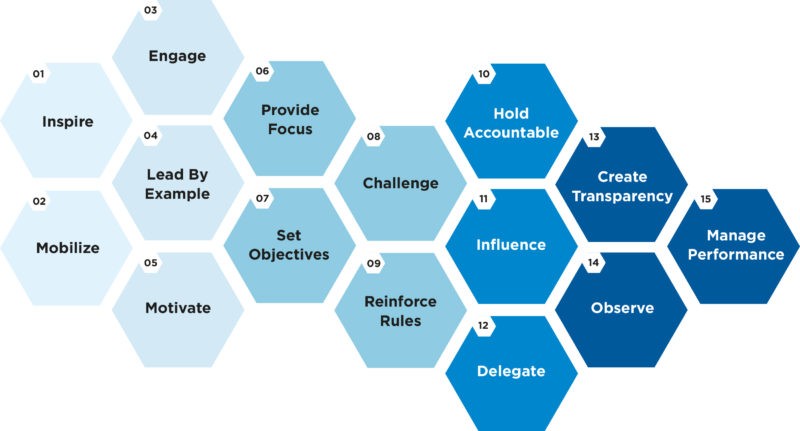

DSS has developed a DuPont Safety Management Competencies Model that aligns critical leadership capabilities with different stages of organisational cultural maturity. Depending on the cultural maturity of a company, coaching can help to develop the competencies required to take the organisation to the next level.

For companies that want to go beyond providing individuals with a skill set that allows them to understand and execute corporate goals, but also want to enable them to develop additional competencies, coaching is the answer. The DSS coaching approach provides business leaders with a sounding board and an advisor who can help to develop and strengthen the capabilities that are vital for effective leadership when transforming the culture in an organisation. “Coaching helps people to help themselves,” is how one of the DSS customers once summed it up. “There is no instructor, just someone who supports you in finding your own solutions.” That is what makes coaching not only effective, but sustainable in the long term.

For companies that want to go beyond providing individuals with a skill set that allows them to understand and execute corporate goals, but also want to enable them to develop additional competencies, coaching is the answer. The DSS coaching approach provides business leaders with a sounding board and an advisor who can help to develop and strengthen the capabilities that are vital for effective leadership when transforming the culture in an organisation. “Coaching helps people to help themselves,” is how one of the DSS customers once summed it up. “There is no instructor, just someone who supports you in finding your own solutions.” That is what makes coaching not only effective, but sustainable in the long term.

[2] John Whitmore, Coaching for Performance, 5th edition, p. 23

[3] Smither, J.W., London, M., Flautt, R. et al. (2006). Can working with an executive coach improve multisource feedback ratings over time? A quasi-experimental field study. Personnel Psychology, 56, 23–44.

[4] Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., van Vianen, A.E.M. (2013). Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9, 1-18

[5] Jones, R.J., Woods, S.A. & Guillaume, Y. (2014, January). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of executive coaching at improving work-based performance and moderators of coaching effectiveness. Paper presented at the British Psychological Society Division of Occupational Psychology Annual Conference, Brighton.

Advance your career in health and safety

Browse hundreds of jobs in health and safety, brought to you by SHP4Jobs, and take your next steps as a consultant, health and safety officer, environmental advisor, health and wellbeing manager and more.

Or, if you’re a recruiter, post jobs and use our database to discover the most qualified candidates.

DuPont Sustainable Solutions (DSS) is an established operations and safety management consultancy that offers specialist risk management coaching as part of its DuPont Risk Factor programme. DSS helps senior executives and middle management boost soft skills with the coaching that the consulting firm has developed.

DuPont Sustainable Solutions (DSS) is an established operations and safety management consultancy that offers specialist risk management coaching as part of its DuPont Risk Factor programme. DSS helps senior executives and middle management boost soft skills with the coaching that the consulting firm has developed. For companies that want to go beyond providing individuals with a skill set that allows them to understand and execute corporate goals, but also want to enable them to develop additional competencies, coaching is the answer. The DSS coaching approach provides business leaders with a sounding board and an advisor who can help to develop and strengthen the capabilities that are vital for effective leadership when transforming the culture in an organisation. “Coaching helps people to help themselves,” is how one of the DSS customers once summed it up. “There is no instructor, just someone who supports you in finding your own solutions.” That is what makes coaching not only effective, but sustainable in the long term.

For companies that want to go beyond providing individuals with a skill set that allows them to understand and execute corporate goals, but also want to enable them to develop additional competencies, coaching is the answer. The DSS coaching approach provides business leaders with a sounding board and an advisor who can help to develop and strengthen the capabilities that are vital for effective leadership when transforming the culture in an organisation. “Coaching helps people to help themselves,” is how one of the DSS customers once summed it up. “There is no instructor, just someone who supports you in finding your own solutions.” That is what makes coaching not only effective, but sustainable in the long term.