The Industrial Injuries Advisory Council provides the Government with authoritative, evidence-based risk assessments for the prescription of occupationally acquired conditions attracting Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit. Paul Faupel explains its work and how health and safety professionals can help.

The ‘father of occupational medicine’, Bernardino Ramazzini, once observed: “When you come to a patient’s house, you should ask him what sort of pains he has, what caused them, how many days he has been ill, whether the bowels are working and what sort of food he eats. So says Hippocrates. I may venture to add one more question — what occupation does he follow?”

Rather more pertinently, Ramazzini also noted: “Many an artisan has looked to his craft as a means to support life and raise a family but all he has got from it is some deadly disease, with the result that he has departed this life cursing the craft to which he has applied himself.”

Even in the context of the modern world of work, with its preventative, risk-based health and safety regulation, these two quotations remain relevant.

Despite improvements made to worker protection, work-related injury and acute or pernicious disabling diseases that are caused by work continue to be a problem. They not only blight the lives of those affected but also impose social and economic burdens.

This is where the Industrial Injuries Advisory Council (IIAC) and its work come in. Established by the National Insurance (Industrial Injuries) Act 1946, the IIAC is a statutory scientific advisory body that is run independently from the Government.

Using scientific evidence, the IIAC advises the Secretary of State for Work & Pensions on the prescription of occupationally related injuries and diseases that are eligible for industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB). IIDB is a type of no-fault compensation that workers affected by the prescribed conditions can claim.

However, the road to modern day state compensation for workplace injury and ill health is a long one and, to fully appreciate the IIAC’s advisory role, it’s necessary to go back to 1897 when the Workmen’s Compensation Act (WCA) came into force. This placed a duty on employers to compensate their employees for any loss of earnings due to accidents arising “out of and in the course of employment”. It was not necessary to show negligence in the causation of an accident.

In 1903, subsequent case law defined an “accident” as an event “which is neither expected nor designed”. Three years later workmen’s compensation was extended to cover both accidents and diseases caused by work. The diseases were prescribed in a scheduled list. The first six were — anthrax, ankylostomiasis and poisoning, or its consequences, by arsenic, lead, mercury and phosphorus.

But lists need updating as circumstances change and new events arise. In 1907, the Samuel Committee handled this by stating that for a disease to be prescribed it had to be a) outside the category of diseases within the ambit of the WCA; b) a cause of incapacity to a worker for more than a week; and c) so specific to the employment that causation could be assumed in the individual case.

The latter is significant. Although a disease may be associated with a particular industry, it could not be prescribed if it occurred in the general population. For example, flax workers suffered from bronchitis but it’s a common disease of society at large.

However, the 1897 act had two fundamental flaws: (a) employers had to insure themselves against liability from potential claims; and (b) workers had to lodge their claims and take civil action if the claims were rebutted.

In 1944 Beveridge’s report on “Social Insurance Part 2 Workmen’s Compensation: Proposals for an Industrial Scheme” identified the disproportionate social costs between administering the system and the cost in benefits to the sick and injured.

Implemented as the National Insurance (Industrial Injuries) Act 1946, the legislation transferred the burden of administration and payment of benefits from the employers and their insurers to the state under a no-fault compensation scheme funded through national insurance — creating the IIDB.

The nature of the compensation also changed; no longer did it cover loss of earnings, rather it was “loss of faculty in proportion to loss of health, strength and the power to enjoy life attributable to industrial accident or prescribed disease”. IIDB is not part of the regime of other employment benefits; a dedicated team in the Department for Work & Pensions (DWP) administers it.

The IIAC is a tripartite body representing employers, employee organisations and specialists (occupational health physicians and hygienists, and lawyers). The Secretary of State for Work and Pensions appoints members of the IIAC to advise the ministerial post on the prescription of occupationally related conditions that attract IIDB. A DWP-sponsored secretariat including advisors and a member of the Health & Safety Executive, support the IIAC. The recommendations that the IIAC makes to the minister are usually published in command papers. If these are accepted, regulations are drafted and made law through the parliamentary process.

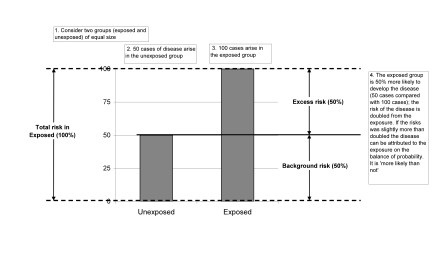

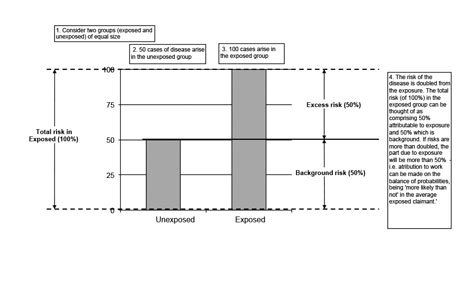

Prescription of a condition depends on crossing the threshold of a doubling of risk exposure in the occupation when compared with the risk to the general population. Sometimes evidence may be persuasive that a condition is occupationally caused but is insufficient to pass this test. In these circumstances, the IIAC publishes a position paper or information note (see table 1).

In addition to the full council’s work, there is a smaller research-working group (RWG) that includes several IIAC members. It is the engine and horizon scanner that drives the work of the IIAC to ensure that it is focused on appropriate issues and reports back to the full council. Any IIAC member may raise an issue for investigation and requests also may come from the Secretary of State or a minister, members of parliament, trades unions, employer organisations, professional institutions, lobbying groups and the general public.

(Xhead) Occupational diseases

The Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act 1992 states that the Secretary of State may prescribe a disease where he is satisfied that the disease:

a) ought to be treated, having regard to its causes and incidence and any other relevant considerations, as a risk of the occupation and not as a risk common to all persons; and

b) is such that, in the absence of special circumstances, the attribution of particular cases to the nature of the employment can be established or presumed with reasonable certainty.

In other words, a disease may be prescribed if there is a recognised risk to workers in an occupation, and the link between disease and occupation can be established or reasonably presumed in individual cases.

For some diseases attribution to occupation can flow from specific clinical features of the individual case. For example, the proof that an individual’s asthma is caused by their occupation may lie in its improvement when on holiday and regression after returning to work, and in the demonstration that they are allergic to a specific substance, encountered only at work.

It can be that a particular disease only occurs as a result of an occupational hazard (e.g. coal workers’ pneumoconiosis); or that cases of it rarely occur outside the occupational context (e.g. mesothelioma); or that the link between exposure and illness is fairly abrupt and clear-cut (e.g. several of the chemical poisonings and infections covered by the scheme). In these circumstances, attribution to work is relatively straightforward.

Such diseases commonly share a particular time course, having their onset within a job or within a fairly short time of leaving it. The current list which defines the qualifying prescribed diseases and their associated occupational circumstances [Social Security (Industrial Injuries) (Prescribed Diseases) Regulations 1985, Schedule] has continued to evolve from the original 1906 list as further prescribable conditions have been identified over the past 100 years.

In that context, prescription has proved increasingly possible for diseases that have potential non-occupational and occupational causes which, when caused by occupation, are indistinguishable clinically from the same disease occurring in someone who has not been exposed to a hazard at work. Examples include lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and osteoarthritis of the knee. Other factors at play in the general population (e.g. smoking, recreational knee injury) account for a proportion of such cases and no clinical features in the individual claimant allow reliable attribution to employment.

In such cases occupational attribution rests on a probabilistic assessment, based on robust research evidence ideally drawn from several independent studies, that work in a prescribed job or with a prescribed occupational exposure increases the risk of developing the disease by a factor of more than two (figure 1).

This in turn makes it more likely than not, on the balance of probabilities, that an individual claimant fulfilling the terms of prescription can be presumed to have the disease because of the exposure, all as defined in the schedule.

The council seeks such research evidence, recommending prescription only where evidence is sufficiently compelling of a causal link to a given occupational exposure.

Recommendations for prescription published in command papers cite the evidence base underpinning the IIAC proposal and they are authoritative, evidence-based risk assessments of particular agent-disease combinations, judged by experts against the civil standard. Since research evidence of this nature and quality can be cited in claims in civil actions and employment tribunals they are potentially an important source of information and reference for health and safety professionals generally and in certain employment sectors in particular.

But what happens when there is insufficient evidence to justify prescription? The evidence base is crucial to the council’s work. The IIAC must make its recommendations based on sound research findings otherwise its credibility as an independent scientific and advisory committee would be undermined.

The doubling of risk threshold test is a critical factor in IIAC deliberations and decisions. What happens if there is insufficient evidence to pass the test in relation to an alleged occupationally caused ill health condition? Table 1 lists some conditions recently considered by IIAC that have not been recommended for prescription. Instead, it published either a position paper or an information note.

Position papers are IIAC reports that detail reviews of specific topics that did not result in recommendations requiring changes to the relevant legislation. Information notes are short summaries of IIAC reviews that did not result in recommendations for changes to legislation and where the evidence base is still emerging, and likely to change, or there was insufficient quantity or quality of evidence to warrant a position paper.

Although the scientific advisor, among other things, supports the IIAC in monitoring the scientific literature, the council is proactive in calling for evidence when it is investigating particular topics. In August 2012 it called for additional research evidence about noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) and use of percussive tools such as road-breakers and jackhammers used on concrete or roads.

This is where the health and safety profession could help. The remit of IIAC is focused on the compensatory IIDB. Conversely, the health and safety profession’s primary focus is prevention. These are complementary endeavours with different emphases.

Health and safety professionals are more numerous in the work environment than the members of any of the partner professions with which they work, such as occupational health, occupational hygiene, ergonomics and risk management.

They are able to observe directly how the work environment can adversely affect workers’ health. They may have encountered issues covered in the reviews in table 1 and may have access to evidence or information that was not captured by the IIAC reviews. Breast cancer and shift working is a particularly important issue; it is a very active area of current research interest and the council continues to monitor new evidence on the topic as it is published.

Health and safety professionals are strong and effective networkers and constantly share information and experience, particularly when seeking solutions to problems. This is potentially a powerful resource for the collection and collation of evidence that could be passed on to IIAC.

(Author details) Paul Faupel is an employer representative appointee to the IIAC — see page 4 for more details.

The IIAC is holding a public meeting in Edinburgh on 19 June. For more details about this and how you can help, visit: www.iiac.independent.gov.uk

Figure 1:

Table 1:

What makes us susceptible to burnout?

In this episode of the Safety & Health Podcast, ‘Burnout, stress and being human’, Heather Beach is joined by Stacy Thomson to discuss burnout, perfectionism and how to deal with burnout as an individual, as management and as an organisation.

We provide an insight on how to tackle burnout and why mental health is such a taboo subject, particularly in the workplace.