By Ian Pemberton

By Ian Pemberton

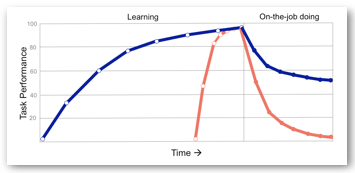

Connect via LinkedIn

Cast your mind back to when you were at school or college. Do you remember what it was like a few days before that important exam? There you are burning the midnight oil revising like mad. You did this by going over the same material – repeating it time and again until you had committed it to memory. After this short intense revision you take the exam and are able to show that you had indeed learnt quite a lot. However, you may also recall that in quite a short space of time you had forgotten a lot too. If you had to retake the exam even a month later you would have been in trouble. This is what psychologists call the ‘cramming effect’. If our learning is bunched-up into a short space of time we learn a lot but quickly forget it. The graph below illustrates this effect which is known as the ‘forgetting curve’ (see Thalheimer 2006 for a review of the literature):

If you think about it, a lot of health and safety training is even worse than high school cramming. Unlike your revision, which at its most extreme may have occurred over several days (i.e. two to three repetitions), a lot of our training consists of single events during which we expect trainees to have learnt all they need and then to go back to their workplace and apply what they have learnt. But, as we have seen, they receive zero feedback in helping them apply what they learnt.

This is not just completely unrealistic, it’s also scary. What the research on the forgetting curve shows is that:

- After 1 hour trainees will have forgotten approximately 50% of the information your course have delivered – yes 1 hour!

- After 24 hours, they will have forgotten around 70% of new information, and

- Within 1 week, they will have forgotten on average 90% of it.

This is an appalling situation and is the dirty secret of health and safety training. The way most of it is delivered means that nearly everything taught to employees will be forgotten. Our approach runs contrary to how adults learn and if we are to have any chance of developing skilled behaviour that is applied in the workplace we need to work with the science, not against it.

So what does the research on learning and forgetting tell us? The first thing is that skilled behaviour can only be developed gradually over time. It does not happen as one event. To be developed, it has to be repeated (i.e. practised) over a period of time.

The spacing of these repetitions is also very important and is what’s called the ‘spacing effect’ (Thalheimer 2006). Take a look that this graph:

The blue line compares what happens if we provide more opportunities to repeat the learning, and, over a longer period of time. The learning becomes far more durable with much better long-term retention. What this shows is that repetition is good, but spaced repetition is even better!

This spacing effect is one of the most studied phenomena in learning research and yet one of the most under-utilised in training. It is like the aspirin of training design – a miracle drug with multiple benefits and few side-effects. Some key findings of the research are:

- Longer spacing intervals tend to be better than shorter ones – spacing should be a minimum of one-day intervals. There seems to be little benefit in repetitions at shorter intervals than this.

- Spacing may not produce an effect unless there are more than two or three repetitions.

- It is important to differentiate between two types of repetitions – 1. Presentations (e.g. classroom theory) and, 2. Practice-feedback (e.g. hands-on doing). What the research shows is that gradually increasing the spacing of practice-feedback is beneficial – whereas there is no benefit in increasing spacing of presentations.

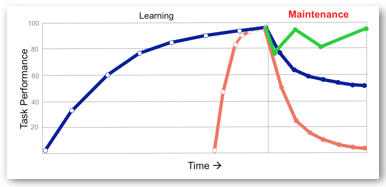

What you will no doubt have also noticed from the above graph is that regardless of the arrangement of the repetitions, whether long or short, the behaviour will deteriorate over time unless it is reinforced by practice-feedback sessions – where trainees receive feedback on their performance so that they can correct/improve their actions. This is why experienced employees with well-developed skills are just as prone to have accidents – their behaviour will naturally deteriorate from the ideal model over time unless they are helped to consciously correct it.

Take as an example the Piper Alpha oil-rig disaster, which was in part caused by a slow deterioration of the rig’s permit to work system. Over time, the parties involved gradually stopped following the system and it became a meaningless paper exercise. This effect has been termed a ‘drift into failure’ (Dekker 2011).

And so, the science tells us that training is not a one-off event – it’s a continuous process. Skills are only developed and maintained by on-going practice-feedback sessions – depicted by the third, green line in the diagram below. The spacing of these maintenance sessions (after a skill has been developed) can be gradually increased and the type of feedback provided will need to change as the skill and experience of the trainee increases.

What all this means is that we have to break free from the traditional model of a ‘training event’ where the belief is that learning has clear starting and stopping points. To get effective behavioural change, which is maintained over time, we need to provide an on-going programme of carefully scheduled practice-feedback sessions. If these are to be a practical exercises that have any chance of happening they have to be short and easy to administer and delivered in the workplace. They have to become part of routine workplace monitoring/checks that are already being undertaken. It’s another reason why the focus of our training needs to move from the classroom to the workplace and be firmly placed in the hands of those at the sharp end.

It also means that we cannot rely on cramming trainees’ heads with information – they will just forget most of it in a short space of time, particularly if the behaviour is not performed regularly, i.e. daily. We have to find ways of delivering the supporting information they need (i.e. reminders of what they need to do), when they need it, and where they need it (i.e. in the workplace as they are doing it). This is so called ‘learning at the moment of need’, where information is delivered by smart work aids, on-the-job.

One good example of this how this works is the Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) in Glasgow (IRISS 2012). As early as 2008, they implemented a ‘learning at the moment of need system’ using Sony PSP game consoles – these are powerful mobile computers with in-built cameras. As Keith Quinn, Senior Education and Workforce Development Adviser explains:

“So for example you put a [QR] code on a locked drugs cabinet in a residential unit for older people – then when you point the camera at it [on the mobile] – you can have a video of somebody talking to you, a member of staff saying ‘remember, when you take drugs out of this cabinet you have got to fill in certain bit of paperwork – here is what that looks like. So what you are doing is actually delivering the learning as they are applying it. The idea is to get the distance between the learning and the application as short as possible.

And outcome of this process?

“…learners, said that they found it much easier to apply the learning with the PSP because they were actually doing the work in the place where they were going to apply the learning”

“Managers loved the flexibility that the system offered. One manager even said that what they liked about it was there was no place to hide. The fact that somebody was learning was much more visible in the workplace, because they were learning in the workplace.” (Keith Quinn)

More recently, SSSC have extended this system for training care workers who visit disabled clients who are based at home and who are bed bound (IRISS 2014). Here is their report of this application:

“Jim is 22 years of age and has significant moving and assisting requirements. KEY support staff operate a ceiling mounted tracking hoist to transfer Jim from his bed to wheelchair, to shower chair, and to and from the bath. Fitting the sling requires a particular technique, which could be difficult for support staff who hadn’t used it for a while.

While all support staff are trained in moving and assisting, the PSP offers a refresher video on how to operate Jim’s hoist. Pointing the PSP at the marker code affixed to [Jim’s] hoist triggers the video.

An additional benefit is that the video shows not just a hoist, it shows Jim’s hoist, which fits well with KEY’s policy of delivering training as close as possible to individuals in the their own home, using its own small team.”

Sandy Marshall, the health and safety training officer involved in this project says:

“Being aware of how Jim reacts to certain moves and being able to actually hear how he reacts can take some of the anxiety out of workers, especially people new to supporting Jim.”

(View an example SSSC video)

This is an excellent example of the need for context specific training delivered at the moment of need. Please note the staff involved in the project also receive general lifting and moving training (i.e. a formalised classroom course) but this system recognises this is only the first step in an on-going process that needs to be extended into the workplace. It demonstrates how we can overcome the compartmentalisation of operational knowledge – every SSSC care worker who now visits Jim has the benefit of the learning from the entire team at their finger tips.

A short video presentation of this article can be viewed here.

References

Dekker S., (2011) Drift into Failure – From Hunting Broken Components to Understanding Complex Systems, Ashgate Publishing, London, England,

IRISS (2012) Mobile learning in the workplace – a cost effective approach to improving learning retention

Thalheimer W. (2006) Spacing Learning Over Time, Work-Learning Research Inc. (a review of the literature)

Ian Pemberton is a chartered ergonomist who has a specific interest in the psychology of adult learning. He helps implements solutions for job-skills development and employee competency from a health and safety perspective. Ian is Managing Director of Human Focus. Contact via LinkedIn here.

Advance your career in health and safety

Browse hundreds of jobs in health and safety, brought to you by SHP4Jobs, and take your next steps as a consultant, health and safety officer, environmental advisor, health and wellbeing manager and more.

Or, if you’re a recruiter, post jobs and use our database to discover the most qualified candidates.