security

Facial recognition: ‘Contrary to popular belief, it hasn’t been developed to ‘spy’ on the public, but to make them safer.’

Facial recognition systems have been around for longer than many might think, as Adam Bannister, Editor of our sister site IFSEC Global, explains.

However, they’ve long been too expensive and inaccurate for most applications – until recently.

Fuelled by advances in processing power and artificial intelligence, algorithms have grown vastly more sophisticated and prices have fallen to commercially viable levels.

Now a tipping point has been reached and investors are jostling for a piece of a burgeoning market, which is projected to quadruple in size to £11.7bn by 2026 from $4bn in 2017.

Countless start-ups are finding substantial funding easy to come by. Horizon Robotics, a Chinese developer of AI-powered facial recognition software, recently raised up to $1bn from bluechip investors, for instance.

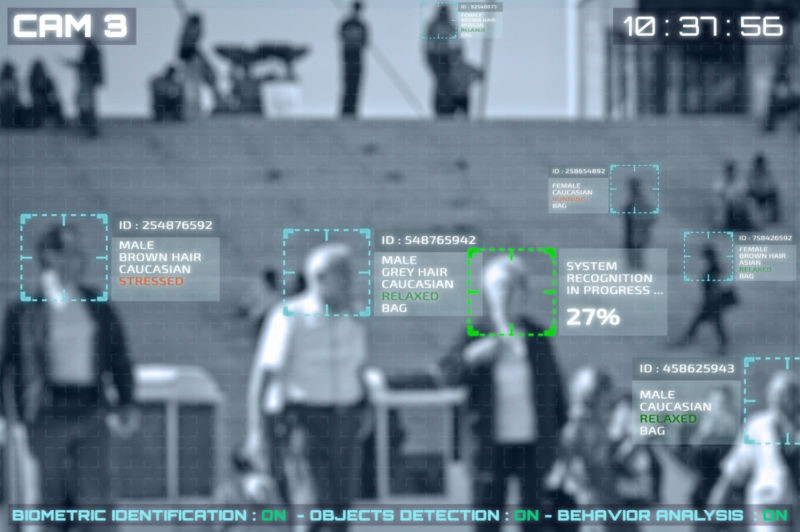

Unencumbered by democratic checks, China is by far the most enthusiastic adopter, deploying the technology at a rapid rate – raising concerns about the growth of an Orwellian surveillance state.

But privacy campaigners are also concerned about the technology’s potential for misuse in countries with more democratic oversight. Liberty and Big Brother Watch are both launching legal claims based on privacy objections against police forces.

A powerful way of identifying citizens was always going to provoke a backlash from some politicians, privacy campaigners and concerned members of the public.

But the CEO of a pioneer in the field believes development is driven by a desire to protect the public and – providing organisations procure systems with appropriate privacy protection – the technology can focus on suspected criminals and “ignore everyone else”.

“Contrary to popular belief, facial recognition hasn’t been developed to ‘spy’ on the public, but to make them safer,” said Zak Doffman, CEO of Digital Barriers. “It enables a more proactive form of policing, and can help clean both weapons and criminals off the streets in an effort to prevent crimes from happening in the first place.”

Doffman says its technology “can match faces in crowded public places against criminal watch lists, and register faces that match with those on watch lists – whilst ignoring everyone else.”

Relatively uninformed

Regulation is now playing catch-up with the acceleration in deployments and its widening array of capabilities. Those capabilities go beyond facial analysis, with people potentially identified by their gait and way they walk.

And the public remain relatively uninformed about the true risks, capabilities and potential.

There will also be concerns that in the gold rush many cheaper solutions that neglect the privacy of citizens and have substandard cybersecurity protections will gain a foothold in public spaces.

The technology undoubtedly makes it easier to identify wrongdoers and can strengthens security checks, either as a supplement to passports and other ID or on its own. And in the UK in particular, it arrives in a market with powerful infrastructure already in place: the roughly 5.9 million CCTV cameras operating across the country.

Major banks are supplementing passwords with facial recognition on their online banking services. It goes beyond security: retailers are beginning to use the technology to evaluate their customers’ in-store behaviour and verify the age of customers. Facial recognition is even being touted as a way to pay for goods and services.

The technology doesn’t just enhance security but speeds up security checks and reduces the hassle and time involved for citizens. A machine installed at five e-passport gates at Heathrow Terminal is scanning both passports and faces to reduce queuing times.

The technology could ease the bureaucratic nightmare in the offing because of Brexit. The Home Office has awarded a contract to UK-based facial verification company iProov to ease passport queue congestion at the border.

Airport unions were concerned about lost jobs but Nick Whitehead, head of strategic partnerships at Aurora, the firm that provides the software to Heathrow, told the Telegraph that “if they are deployed as an aide to officers that takes away the mundane tasks.”

Facial recognition’s maturation into a commercially viable product couldn’t be more timely given budgetary constraints on law enforcement, Zak Doffman believes. “In policing, facial recognition can enable our strained resources to do more. If a police officer could memorise the faces of every person of interest or vulnerable member of society before going on shift they would. It would enable them to be more effective and proportionate with all of their day-to-day interactions.

Digital Barriers’ facial recognition technology can identify people in a crowd, live, from CCTV, body worn cameras, police dash cams and mobile phones.

“Digital Barriers’ facial recognition engine is in use every day of the week by defence and counter-terrorism agencies around the world to keep the public safe from harm,” said Doffman. “We have expanded the capability to work with mainstream policing on body worn cameras, and to focus on recognising vulnerable members of society, such as those with dementia or runaways or self-excluding gamblers to help to safeguard them.”

Facial recognition: ‘Contrary to popular belief, it hasn’t been developed to ‘spy’ on the public, but to make them safer.’

Facial recognition systems have been around for longer than many might think, as Adam Bannister, Editor of our sister site IFSEC Global, explains.

Adam Bannister

SHP - Health and Safety News, Legislation, PPE, CPD and Resources Related Topics

UK energy sector unites for AI and digitalisation

Higher demand but not able to meet it – survey finds health and safety provision lacking for staff

How will AI transform health and safety?

yet the met police are rolling it out, in an attempt to identify people wanted for arrest, if that isnt spying what is?