Each month, SHP asks a professional working in a specialist field to share their expertise. To coincide with IOSH’s No Time to Lose campaign, Professor John Cherrie from the Institute of Occupational Medicine (IoM) provides an outline of the health risks associated with diesel engine exhaust and the steps that can be taken to reduce these.

What is it about diesel engine exhaust that is harmful to health?

Diesel engine exhaust is a complex mixture of particles and gasses. If you work around diesel engines you can see and smell the exhaust and so it is immediately apparent when you are exposed to these high concentrations. However, the exhaust emissions disperse into the surrounding air and are no longer easily detected, but this does not mean that there is no risk; low levels of diesel engine exhaust can still increase your risk for cancer and other serious diseases.

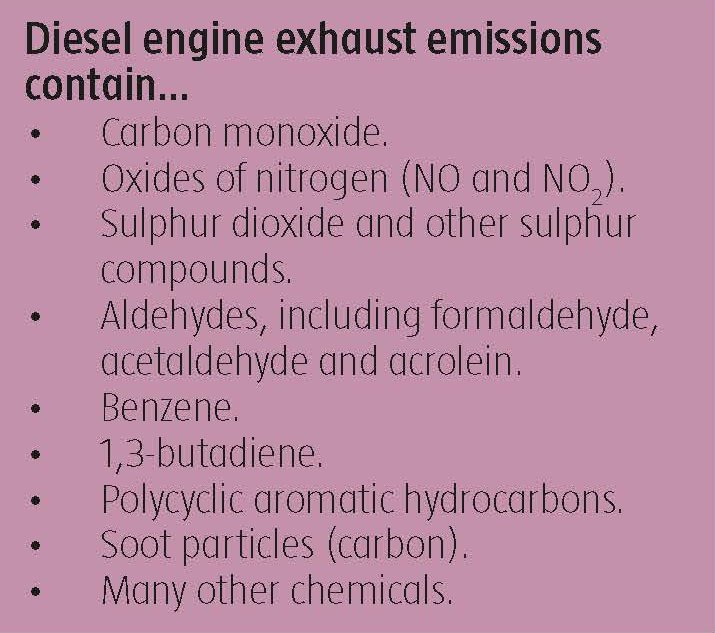

The main constituents of diesel engine exhaust are listed (see box, right). The harmful gasses mainly comprise aldehydes such as formaldehyde, along with benzene and carbon monoxide. In the past some authorities recommended using carbon dioxide, which is also emitted from diesel engines, as a marker of unsuitable conditions but this is not now considered a reliable method.

The main constituents of diesel engine exhaust are listed (see box, right). The harmful gasses mainly comprise aldehydes such as formaldehyde, along with benzene and carbon monoxide. In the past some authorities recommended using carbon dioxide, which is also emitted from diesel engines, as a marker of unsuitable conditions but this is not now considered a reliable method.

Diesel soot particles are very small, typically much less than 1μm in diameter, and when inhaled may deposit deep in the lung. These particles have a carbon core with many different organic chemicals on their surface, including carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). The solid core is generally referred to as elemental carbon (EC) and the adsorbed hydrocarbons as organic carbon (OC). Individual diesel exhaust particles can stick together to form larger chain-like particles in the air, as shown in the diagram.

What are the main risks to worker health?

Exposure to diesel engine exhaust can cause irritation of the eyes, throat and the upper respiratory tract. These effects are mostly due to the irritant gasses or unburnt hydrocarbons in the exhaust. Acute exposure may also cause neurophysiological symptoms such as lightheadedness and nausea, and respiratory symptoms such as cough or phlegm. People who already have asthma may find their symptoms are exacerbated if they are exposed to diesel exhaust.

Long-term exposure to diesel exhaust particulate, usually measured as the air concentration of EC, can cause cancer. In 2012, the Internal Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) identified diesel exhaust particulate as a cause of lung cancer (sufficient evidence) and also noted a positive connection (limited evidence) with an increased risk of bladder cancer. IARC now classifies it along with asbestos, benzene and ionizing radiation as a known carcinogen (group 1).

There is good evidence that long-term exposure to diesel engine exhaust particulate can also lead to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), particularly in nonsmokers. COPD is the name given to lung diseases, including chronic bronchitis, emphysema and chronic obstructive airways disease. People with these diseases may suffer from breathlessness during activity, persistent cough with phlegm and frequent chest infections.

It seems as though the scientific evidence points fairly clearly at the particulate fraction of diesel engine exhaust as the most hazardous component.

How many people in Britain are exposed

to the risks and what industries and professions are most at risk?

There are probably about 500,000 people exposed to diesel engine exhaust particulate during work in Britain. About half of the most highly exposed are employed in land transport jobs, but about a third are employed in the construction sector, often exposed from off-road vehicles.

Exposed workers may be driving diesel powered vehicles such as fork-lift trucks, railway locomotives, buses and lorries, or may work in environments where diesel engines are operating, such warehouses, locomotive depots, ferries, garages, vehicle testing sites, fire stations and so on. Outdoor workers in cities such as traffic wardens, postal workers, police officers and others are also exposed. There is a diverse range of occupations where workers are exposed to diesel engine exhaust.

Aren’t workers protected under the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations?

Yes, it’s true that the COSHH Regulations apply to diesel engine exhaust particulate because of the hazardous nature of the particles and the gaseous emissions.

Employers have a duty to carry out an assessment of the risk to health for workers who use or are in the vicinity of diesel engines used at work. General advice when carrying out these types of assessment is to make an evaluation of the magnitude and duration of the exposure, and to compare this with the relevant workplace exposure limit.

However, there is no limit value for diesel engine exhaust particulate that allows us to judge the acceptability of the risks for cancer or non-malignant respiratory disease. HSE has recommended using the level of carbon dioxide (above 1,000ppm), but this is not specific to diesel engine emissions and such measurements are only likely to identify the very worst situations. The other signs of very poor control are:

- permanent white, blue or black smoke;

- heavy soot deposits especially near emission points; and

- exposed workers complain of irritancy.

However, lower exposures present an unacceptable risk and need to be controlled.

It is possible that the European Commission will set a limit value based on measuring elemental carbon when they revise the Carcinogens and Mutagens Directive, which is currently under discussion. In the meantime we need to adopt a different strategy, one of progressive improvement in the degree of control based around the principles of good control practice set out in COSHH.

What steps should a responsible employer take to protect their workers?

As a consequence of improved technology modern diesel engines emit much lower levels of particles than older engines. This is primarily due to the introduction of sophisticated platinum-based diesel particulate filters on the exhaust system. As time goes on, the levels on our workplaces will decrease as we replace older technology, but we cannot wait for this to happen. We really need to act now.

The key principles of good control practice require employers to:

- Minimise emission, release and spread of diesel engine exhaust particulate.

Clearly, switching to new diesel technology when it is economically feasible is a good strategy or using electric powered vehicles or other suitable technologies.

Use of cleaner fuels, such as low sulphur diesel fuels, can help. There is consistent evidence that switching from conventional diesel to biodiesel can reduce particulate emissions, although there are other issues around engine performance and there is a slight increase in the emission of nitrogen oxides.

Regular maintenance of diesel engines should help reduce soot emissions.

Consider installing filtered air into the cab of off-road vehicles. Such systems should incorporate a HEPA filter to remove the very fine diesel soot. Check the cabin (or AC system) air filter is functioning, and consider upgrading the filter system to incorporate a HEPA filter. Cabin air filters can reduce in-cab levels by more than 50 per cent.

In enclosed workplaces such as garages, use an exhaust tailpipe hose system connected to an extraction system.

Adopt stop-start technologies when possible, or just switch off the engine when it’s not needed.

Improve the general ventilation in indoor workplaces.

- Choose to control exposure by measures that are proportionate to the health risk.

We are dealing with a carcinogenic agent and so we need to apply a high degree of control, higher than we have traditionally been used to for many of the workers involved. It is not sufficient to assume that working outdoors around diesel vehicles or just driving a truck will result in acceptable exposure. We need to set up systems where we are continually striving to reduce worker exposure to diesel engine exhaust particulate.

- Choose the most effective and reliable control options.

In general it will be most effective to control at the source, i.e. before the soot is emitted into the work area. This can be best done by tackling engine emissions and, where appropriate, using local exhaust systems.

- Use respiratory protection when necessary

There are many situations where it is impractical to control exposure to diesel exhaust particulate, for example, mobile workers such as postal delivery workers. In these situations if you want to control exposure then the only practical way may be to use respiratory protection. While this is not commonly done it is something that we must seriously consider. Note that nuisance dust masks that are often worn by cyclists are ineffective against diesel exhaust particulate and should not be used. Best to select a suitable filtering face-piece respirator.

Are there any tools to help employers measure their workforce’s exposure levels?

You can measure the concentration of respirable elemental carbon in the workers’ breathing zone.

The US National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has published a method for collecting and analysing samples to determine the respirable elemental carbon concentrations. [1]

As well as the chemical analysis it is possible to use a method that determined the “blackness” of the filter from the soot deposit. While this type of analysis does not directly measure elemental carbon it is possible to estimate it with reasonable accuracy. This analysis is quicker and costs less than the chemical analysis.

Samples can be analysed in the UK by the Health and Safety Laboratory (HSL) and by Scientific Analysis laboratories (SAL) Ltd. Cost per sample is around £50.

There are also a number of direct reading instruments that can be used to measure the so-called “black carbon” in the air, which are known as Aethalometers. The microAeth is one of these devices that is small enough to be worn by a worker. Like the filter determination of blackness, measurements of black carbon can be a good agreement with the elemental carbon concentration, although it is important to remember that because these instruments don’t directly measure elemental carbon they can sometimes give erroneous readings. The microAeth costs around £6,000.

Has HSE produced any guidance for employers on diesel engine exhaust?

Yes, the two key HSE publications of interest are:

Control of diesel engine exhaust emissions in the workplace (HSG187, Third edition): http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/books/hsg187.htm

And diesel engine exhaust emissions (INDG286, published 2012): http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg286.htm

HSE also publishes advice about ventilated vehicle cabs in the COSHH Essentials series (it refers to silica exposure but is equally pertinent to diesel emissions): http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/guidance/bk7.pdf

Details of the principles of good control practice can be found on HSE’s website at: http://www.hse.gov.uk/coshh/detail/goodpractice.htm

Where can I get more information?

IOSH have just launched the No Time to Lose campaign, which aims to get the causes of occupational cancer better understood and help businesses take action. There will be a free factsheet on diesel engine exhaust fumes available to download form the website. Find out more about the campaign at: http://www.notimetolose.org.uk

Download a recent webinar hosted by IOSH’s Retail and Distribution Group on the risks from diesel fumes in the logistics sector here.

There is a scientific article about the use of biodiesel that was recently published it is: Song, H., Tompkins, B. T., Bittle, J. A., & Jacobs, T. J. (2012). Comparisons of NO emissions and soot concentrations from biodiesel-fuelled diesel engine. Fuel, 96(C), 446–453.

And another paper about the effectiveness of vehicle cabin air filters: Muala, A., Sehlstedt, M., Bion, A., Sterlund, C., Bosson, J. A., Behndig, A. F., et al. (2014). Assessment of the capacity of vehicle cabin air inlet filters to reduce diesel exhaust-induced symptoms in human volunteers. Environmental Health: a Global Access Science Source, 13(1), 1–14.

The microAeth is made by Aethlabs: https://aethlabs.com

IOSH has just launched its No Time to Lose campaign, which includes a free factsheet on diesel engine exhaust fumes. Visit: www.notimetolose.org.uk

John Cherrie is a principal scientist at the IoM and an honorary professor at the University of Aberdeen. He has a particular interest in occupational cancer and is currently leading a project to benchmark the number of cases of cancer caused by work in the construction sector in Singapore.

Reference

1. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2003-154/pdfs/5040.pdf

The Safety Conversation Podcast: Listen now!

The Safety Conversation with SHP (previously the Safety and Health Podcast) aims to bring you the latest news, insights and legislation updates in the form of interviews, discussions and panel debates from leading figures within the profession.

Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts, subscribe and join the conversation today!