Behavioural safety – intervening in a useful way

Make sure you have identified the behavioural drivers…

Having understood something of the drivers of behaviour using the COM-B model, designing interventions to support changes in behaviour is the next step. Having a sound grasp of the drivers is pivotal, however, because it helps us avoid wasting time and energy intervening in a fruitless way.

For example, Michie et al (2014) describe a re-training initiative that gave advanced driving skills to young drivers, to try and reduce the high numbers of accidents they were having. In spite of focused efforts on skills improvement, accidents remained high because the intervention was dealing with the wrong issue. The training targeted capability – the ability of the youngsters to drive. They had mastered these skills, however, and their accidents stemmed from a motivation not a capability issue. They were motivated to take risks and drive faster than their older counterparts. This lay at the heart of the higher than average accident stats. It was these motivation issues that needed to be addressed in order to achieve behaviour change, rather than the capability issues that the original programme wrongly targeted. Youngsters needed to understand the consequences of driving fast and taking risks, in terms of injuries, higher insurance premiums, loss of the opportunity to drive, etc.

Choosing an intervention strategy

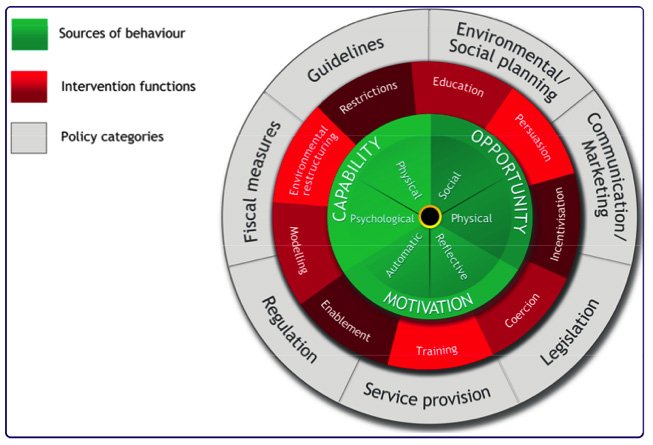

The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) (Figure 1 below) has the COM-B components as its hub, and then nine intervention types in the next layer. The outer layer deals with policy categories that might be useful mechanisms for delivering the intervention types (for example, we might educate (layer 2) through guidelines (layer 3)).

Figure 1: The Behaviour Change Wheel (Michie et al, 2011)

In reality, the outer layer uses language and approaches beyond those of most workplace practitioners. We might intervene in the workplace to restrict certain behaviours (Restriction, layer 2), but this restriction will likely be in the form of rules or procedures, not ‘legislation’ or ‘fiscal measures’ as outlined in layer 3. For that reason, we tend to limit our focus to layers one and two and are working on different terminology for the outer layer so that it better reflects the reality of workplace health and safety practice.

That notwithstanding, the nine intervention types help us consider how to intervene to support change. Table 1 outlines which intervention functions support change in which behavioural elements and gives some health and safety examples.

Table 1: Matching interventions with COM-B elements

| COM-B component | Possible intervention types for this component | Example interventions |

| Capability | Training – imparting skills;Enablement – increasing means/reducing barriers to increase capability (beyond education and training) and/or increase opportunity (beyond environmental restructuring);Education – increasing knowledge or understanding | Training – Dynamic risk assessment skills;Enablement – behavioural support for smoking cessation; medication for cognitive deficits; surgery to reduce obesity; prostheses to promote physical activity;Education – providing information about risk |

| Opportunity | Restriction – Using rules to reduce the opportunity to engage in the target behaviour or to increase the target behaviour by reducing the opportunity to engage in competing behaviours;Environmental Restructuring – Changing the physical or social context;Enablement – see above | Restriction – prohibiting entry to certain areas of the plant;Environmental restructuring – changing work teams to provide different social influences; changing floor plans to separate pedestrians and vehicles |

| Motivation | Persuasion – Using communication to induce positive or negative feelings or stimulate action;Incentivisation – creating expectation of reward;Coercion – creating expectation of punishment or costModelling – providing an example for people to aspire to or imitate; Education – see above; Environmental Restructuring, | Persuasion – using family imagery on posters to motivate speed reduction in road worksIncentivisation – using prize draws to induce attempts to stop smokingCoercion – raising the financial cost to reduce excessive alcohol consumptionModelling – using shopfloor, peer coaches for manual handling (e.g. super handlers) |

An example of an accidentally successful intervention

We worked with a manufacturing company who had tried for many years to reduce road traffic incidents amongst its haulage drivers, with typically cyclical results – at the start of each campaign, incidents dropped a little; reporting dropped a lot. No specific work was undertaken to understand behavioural drivers and then intervene in a targeted way.

However, once the organisation fitted vehicles with a driver-performance tracker (for entirely non-safety reasons) they noticed a dramatic drop in incidents. Interviews with drivers at the time exposed the reason.

Driver data was presented live on screens in the transport office. Returning drivers could see how they ranked against their peers on measures such as “fuel efficiency” and “sympathetic braking/accelerating”. This environmental restructure impacted on social opportunity by changing the norms by which the drivers judged their driving. It also increased capability – in the form of knowledge about driving performance. Instead of the intangible “drive safely” (which had little impact since the drivers all felt that they were “good” drivers and accidents happened to other people), here was a tangible measure and set of behaviours that the driver could directly affect (See article 2 on separating behaviours from outcomes).

The “league tables” provided the motivation to be objectively “the best driver”. The behaviours required to hit those measures (good awareness and anticipation, controlled driving) are of course also those that road safety specialists advocate for reducing road risk. Ultimately, the behaviour was changed by an intervention that concurrently provided increased motivation, capability and opportunity.

Bringing this all together for good…safety behaviour change done well

We believe that supporting safety is all about making it easy to do the right thing. Behavioural safety change simply draws on all that we know about human behaviour and uses this knowledge in combination with our systems thinking approach, to make the right thing the done thing. So good behavioural safety programmes should:

- Take a systems-focused approach – models like the COM-B support this

- Deal with the groundwork first – the constant round of workplace, equipment and system optimisation before the focus moves to individual behaviour

- Be participatory – involve field based experts at every step, with opportunities for two way dialogue and learning

- Be evidence based – deal with work as done, not work as imagined and be sure the real behavioural drivers have been identified

- Intervene appropriately and in an ongoing way – interventions linked with behavioural drivers will be fairer and more successful…and one-off interventions are unlikely to be sufficient.

Our experience has shown that appropriately designed and supported behavioural changes will really yield improvements in health and safety. Organisations stop using behavioural safety as a magic bullet, and instead they take a considered, structured approach; allowing them to put the right resource into the right issues at the right time.

Dr Claire Williams is a senior consultant at Human Applications and a Visiting Fellow in Human Factors and Behaviour Change at the University of Derby. She was the Principal Investigator on the IOSH funded project ‘Measuring the impact of behaviour change techniques on break taking behaviour at work’.

Dr Claire Williams is a senior consultant at Human Applications and a Visiting Fellow in Human Factors and Behaviour Change at the University of Derby. She was the Principal Investigator on the IOSH funded project ‘Measuring the impact of behaviour change techniques on break taking behaviour at work’.

In her role at Human Applications she provides consultancy and training to industry and government organisations in behavior change, human factors and risk management.

This blog is the final in a series of four to be published on SHP online.

The first three articles can be found below:

Safety Behaviour Change

Understanding and identifying safe performance

Understanding behavioural drivers

References

Michie et al (2014). The Behaviour Change wheel – A guide to designing interventions

Michie, S et al (2011): ‘The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions’, in Implementation Science 2011, 6:42 –

Behavioural safety – intervening in a useful way

Make sure you have identified the behavioural drivers… Having understood something of the drivers of behaviour using the COM-B model,

Safety & Health Practitioner

SHP - Health and Safety News, Legislation, PPE, CPD and Resources Related Topics

Workers facing uncertain future coupled with health and safety risks, new IOSH report says

The London Health & Safety Group – over 80 years old and still going strong

New IOSH study centre aims to support Level 6 Diploma

Strange that the young drivers training aimed to improve their practical driving skills? Any defensive / advanced driver training I’ve ever seen has concentrated on hazard perception, forward observation, driving plans etc. all things that can change behaviour and reduce risks and accidents.

Interesting use of LGV telemetrics to reduce harsh driving, which may reduce RTC’s, but it wont stop them jumping down from their vehicle or failing to use a grab handle to gain access etc.

[…] The fourth article of Dr Claire Williams series on Safety Behaviour Change for SHP online titled “Behavioural safety – intervening in a useful way” focuses on choosing the correct behavioural safety intervention strategy, identifies nine intervention types, matches these intervention types to the COM-B Model elements and indicates what good behavioural safety programmes should include. The full article can be viewed on https://www.shponline.co.uk/behavioural-safety-intervening-in-a-useful-way/ […]