Construction on the Thames Tideway Tunnel begins in 2016. Leading up to his presentation at the IOSH conference in June, Steve Howells outlines the project and its ‘safety vision’. Interview by Nick Warburton

London’s Victorian sewerage network has been under severe pressure from population growth in recent decades and is struggling to cope.

Built by Sir Joseph Bazalgette in the 1860s and designed for a population of 4 million people, the sewers are now under demand from a population that is predicted to surge to 8.5 million people by 2030 (not counting the millions of commuters that make their living in London).

A civil engineering milestone in its day, the extensive, subterranean network has simply run out of capacity. In 2013, 55 million tonnes of raw sewage spilled directly into the tidal Thames, and the pollution is only expected to increase unless something is done about it.

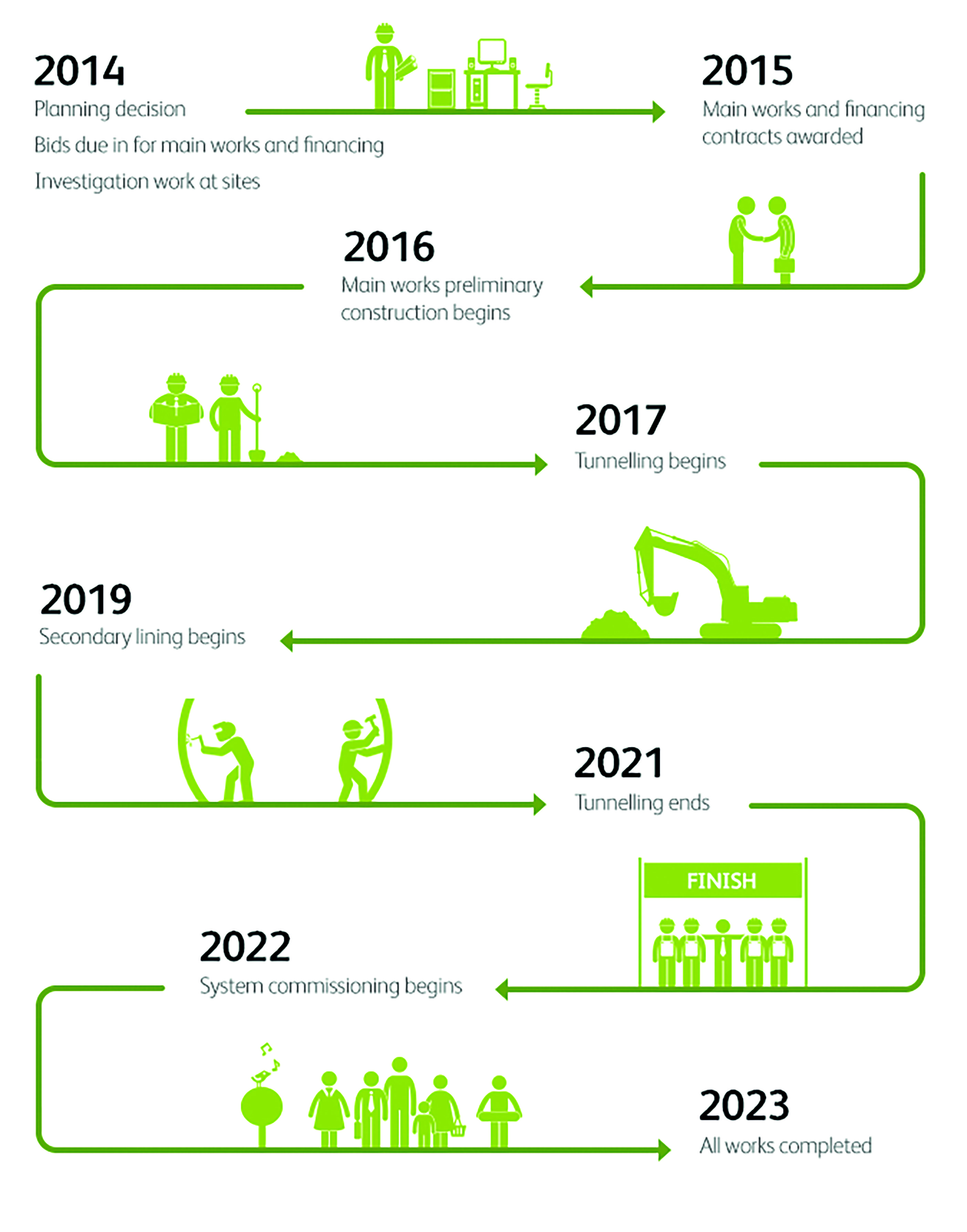

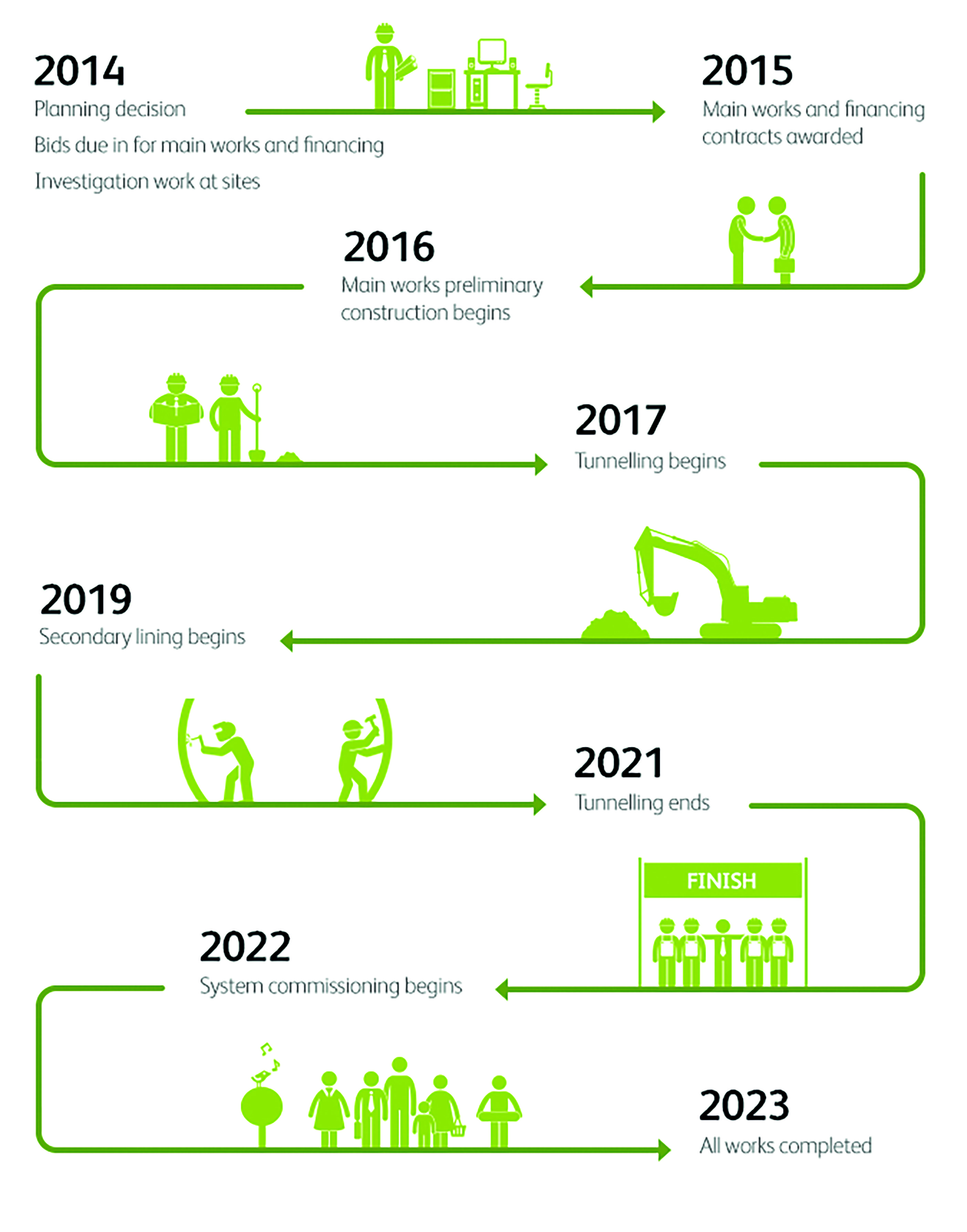

The Thames Tideway Tunnel is the latest landmark project being sketched on to London’s elaborate construction map. Needed for the requirements of the European Waste Water Directive to clean up the Thames, preliminary construction on the super sewer is due to commence in 2016. Earmarked for completion by 2023, the gargantuan project, once fully operational, should provide a solution to London’s overflowing sewers for at least another 100 years.

“We will be intercepting all of the combined sewage overflows and in effect the Thames Tideway Tunnel will be a receptacle for all the waste that is currently discharging in to the river to take it to London’s sewerage works for treatment,” explains Steve Howells, director of HSSE at Thames Tideway Tunnel, who joined the project in May 2014 after working as head of HSE at Heathrow Airport.

Thames Water will manage the asset once it’s finished but first there is the small issue of building the 25-kilometre tunnel. As Steve explains, the project received its development consent order approval last September and is working closely with Thames Water to ensure all enabling work is complete before preliminary building work commences next spring.

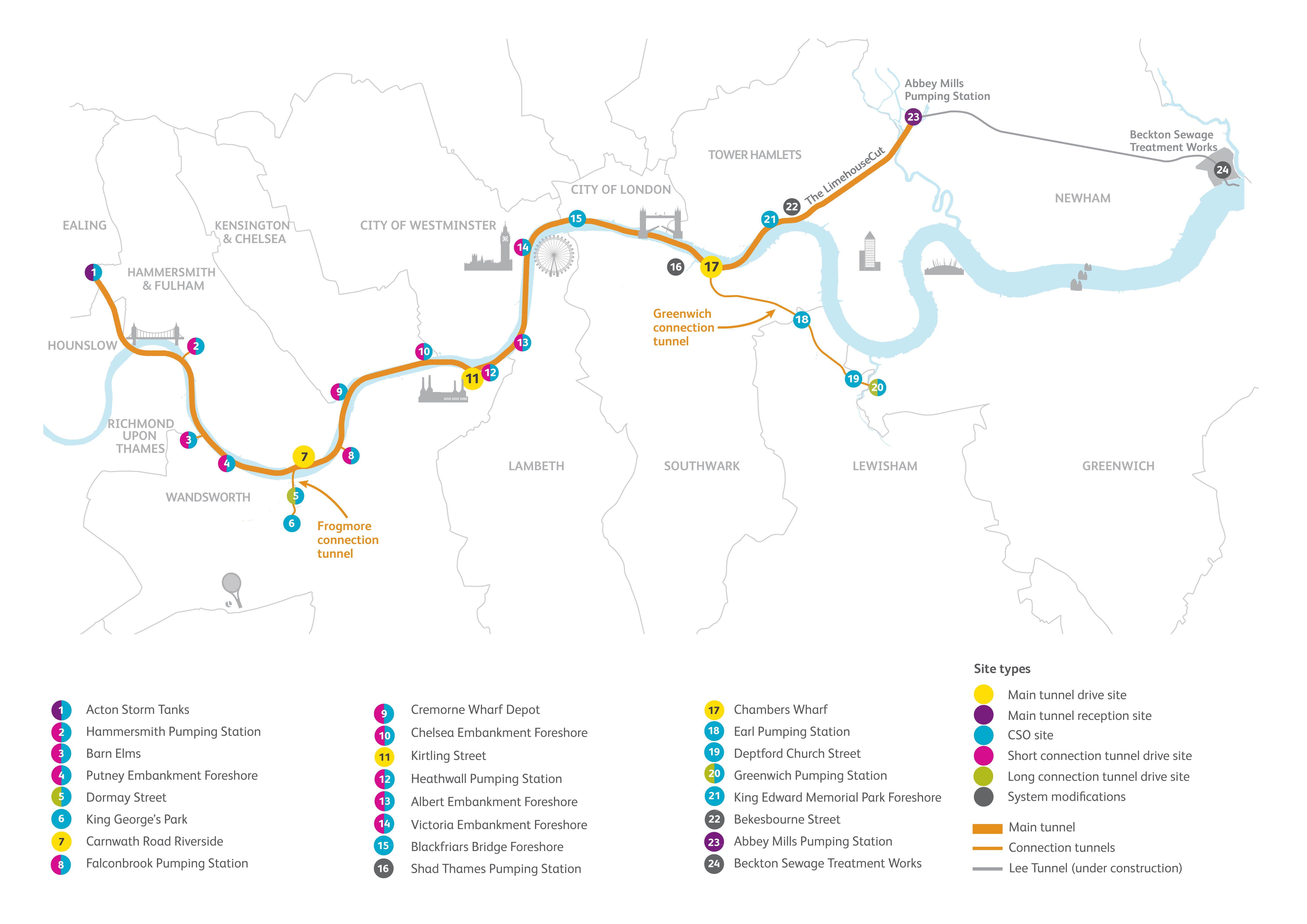

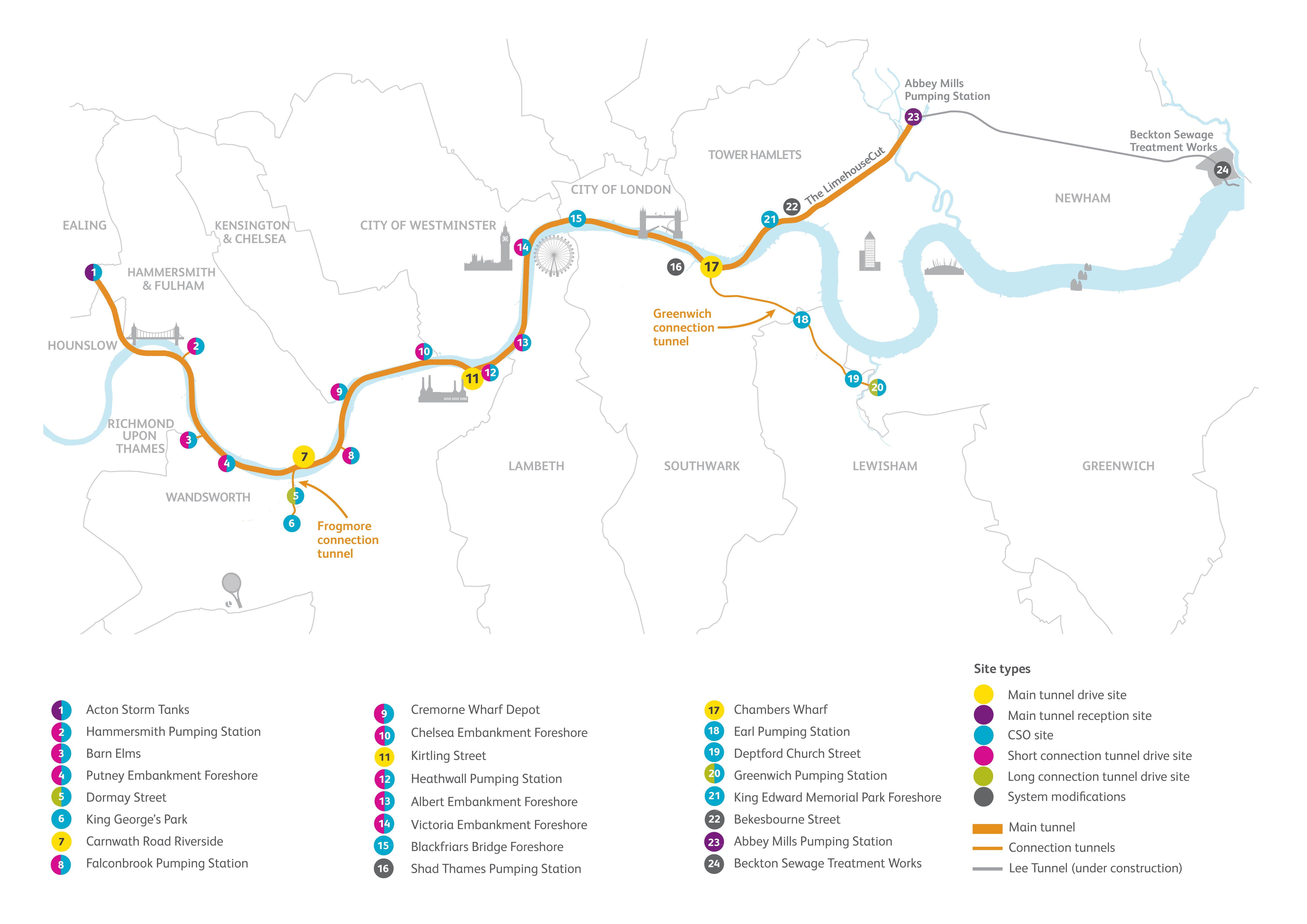

Once completed, the tunnel, which predominantly follows the contours of the Thames, will link Acton Pumping Station in West London to Abbey Mills Pumping Station in London’s east end, not far from the Olympic Park (see map). It is one part of three independent, yet interdependent projects.

Once completed, the tunnel, which predominantly follows the contours of the Thames, will link Acton Pumping Station in West London to Abbey Mills Pumping Station in London’s east end, not far from the Olympic Park (see map). It is one part of three independent, yet interdependent projects.

The first has been Thames Water’s upgrade of existing pumping stations and sewage treatment works. The second is the Lee Tunnel, which eventually will connect with the Thames Tideway Tunnel at Abbey Mills and join on to Beckton Sewage Treatment Works, and the third, and final, link in the chain is the actual Thames Tideway Tunnel from Acton to Abbey Mills.

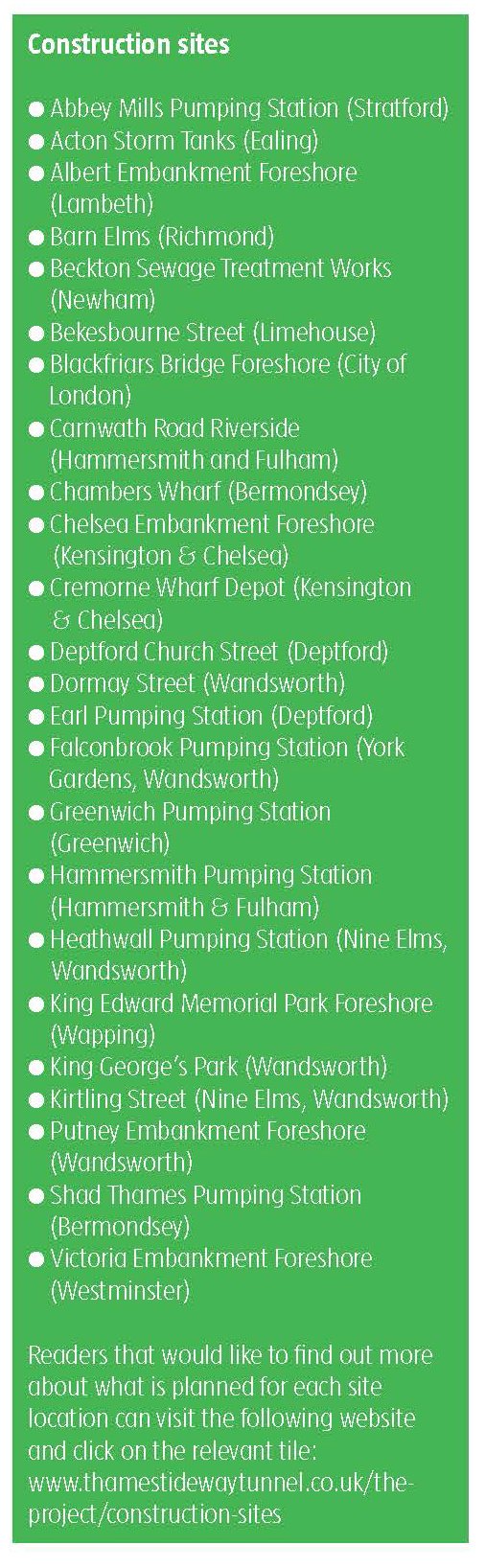

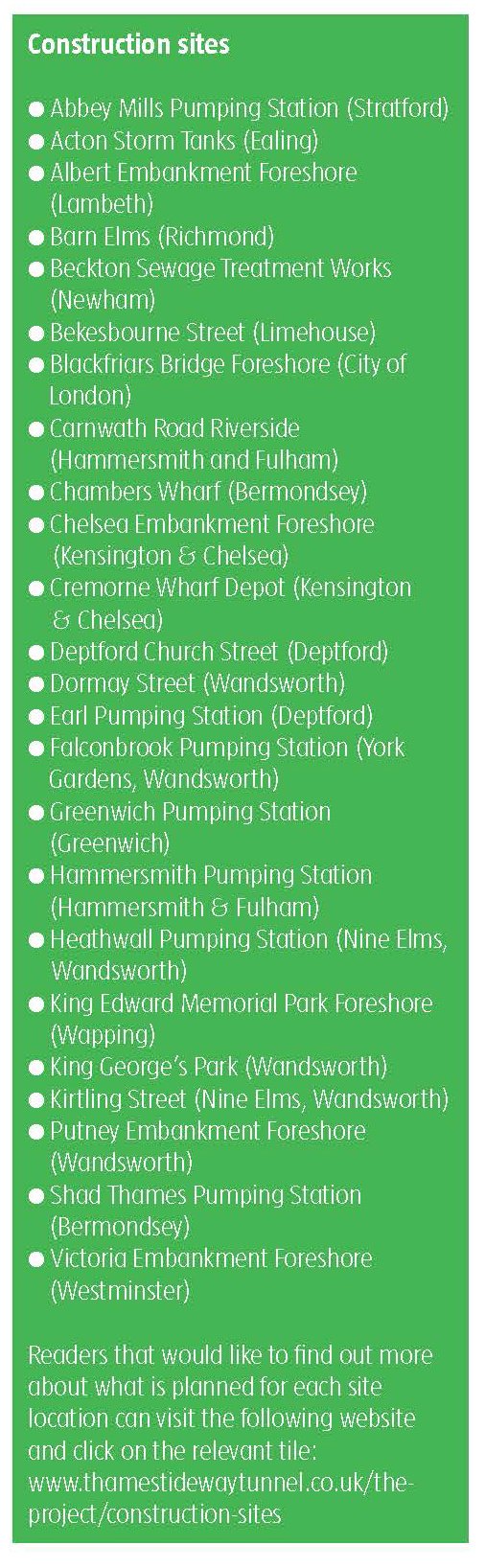

Overall, the Thames Tideway Tunnel project team will oversee the construction of 21 sites along the route, while a further three construction sites will be managed by Thames Water (see box).

Overall, the Thames Tideway Tunnel project team will oversee the construction of 21 sites along the route, while a further three construction sites will be managed by Thames Water (see box).

The project’s main joint ventures are currently at preferred bidder status but Steve anticipates that contracts will be awarded by the summer, which is also when the infrastructure provider, who will cover the finance and debt, will be awarded its licence. After that, the main contractors will sit down to plan the development before undertaking preliminary construction.

“When we first go to mobilisation of the sites, which is probably end of quarter one in 2016, we will have a very clear project execution plan at which point the main works contractors will start to mobilise, certainly at the three main drive sites,” explains Steve.

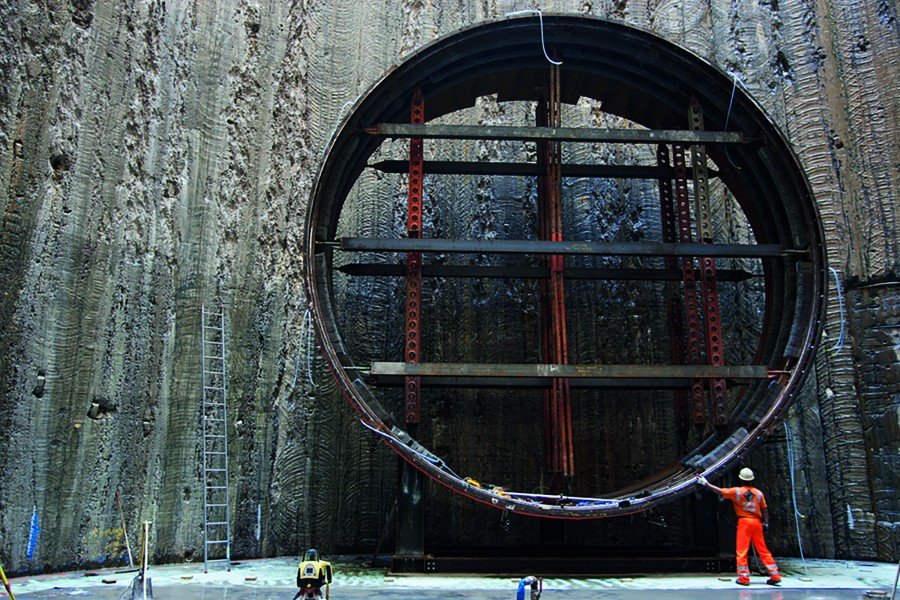

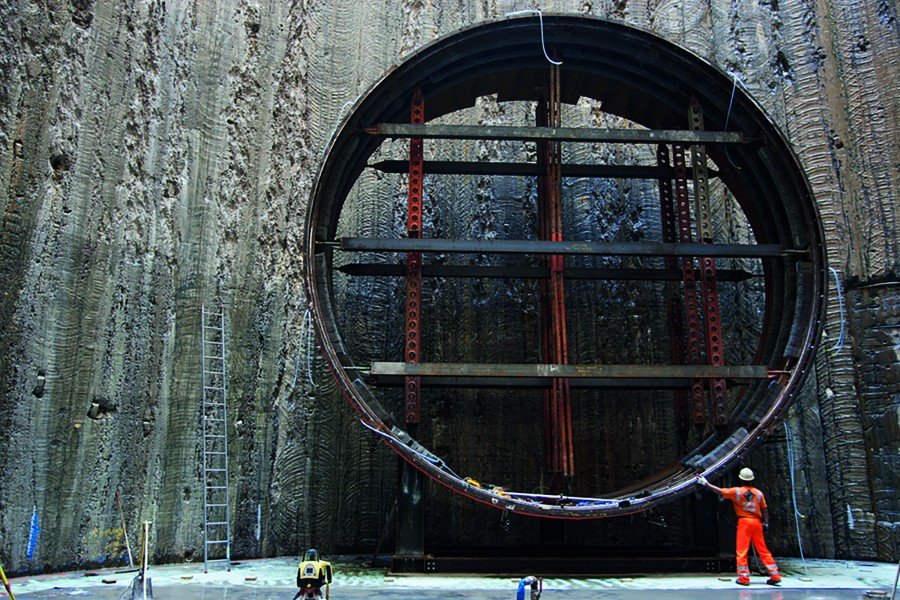

The three main drive sites are Carnwath Road Riverside in Hammersmith and Fulham, Kirtling Street (next to the Battersea Power Station development) and Chambers Wharf in Bermondsey; it is from these three locations that the tunnel bores will clear away earth for the main tunnel to be laid. A smaller tunnel bore will be used to build an additional 7 kilometre, 5.2-diametre tunnel from Chambers Wharf up to Greenwich for the link up with Abbey Mills Pumping Station.

Steve explains that he will oversee a 22-strong team, split across the three project areas (based at the main drive sites), which will each consist of a lead health and safety manager, a health and safety adviser, an environmental adviser and a CDM-integrator, who will support the principal designers. In addition, the main works contractors will bring their own HSSE teams.

Not surprisingly, the project team has drawn on the lessons from London 2012 and the Heathrow Terminal 2 infrastructure project. Due to the similarity in work being undertaken at Crossrail, Steve has also forged close links with his counterpart there, Steve Hails.

Both are members of the innovative Health and Safety Directors, which brings together key players from across the major contractors and companies in the Greater London area in a drive to share best practice.

“The idea is where in the past perhaps we might have been very silo in our thinking in developing a health and safety programme, we now recognise that there is a whole heap of great work that is being done that could and should be replicated elsewhere,” he explains.

Central to the Thames Tideway Tunnel is its Triple Zero vision, an innovative programme that began life about two years ago when the team held several ‘shaping’ workshops to identify exemplary health and safety practice in other sectors like manufacturing, nuclear and the rail industry.

As Steve will explain at this month’s IOSH conference, the project’s ambitious vision is about zero harm, zero incidents and zero compromise in delivering a transformational health and safety performance.

“If we don’t do something fundamentally different to what is currently happening in our industry, we will have fatalities, we will have RIDDORs, we will have high impacts of health incidents, and we will have lots of minor accidents and near misses and that can’t be allowed to happen,” he argues.

“Even if we measure ourselves as being a little bit better than what’s gone before us that will still happen, so clearly it’s not acceptable.”

As Steve points out, one of the first challenges facing his team is how it can avoid the historic ‘incident’ spike that often happens at the start of construction projects when teams are being mobilised and start work.

“The only safety performance that we can absolutely put our heart on saying we are happy with is zero incidents, zero harm and we won’t compromise on that,” he stresses.

Another challenge will be how the project team can maintain everyone’s focus so that a ‘sustainable active safety (SAS)’ programme can be built to reflect the 10-year lifetime of the project. Like the historic spike that often happens at a development’s outset, he is also conscious that the team needs to prevent a similar spike at the end, when teams are demobilising and handing over to the systems integration teams.

“We need to make our programme sustainable so we don’t suffer any of the safety curves. What we are looking to mandate is that every 12 weeks we will stand every work site down regardless of the job they do to reflect on where we are but more importantly to do a 24-week look ahead,” he says.

“We will have a team of safety coaches, safety leaders, and management looking 24 weeks ahead to say, ‘This is where we are going to be in the programme, these are some of the likely hazards we are going to be coming across, so our stand down for 24 weeks’ time will be focused on that’. We will then have a group who will be developing what that day will look like.”

Steve explains that the stand downs could be for an entire shift, or just for an hour but will be appropriate to the stage at which the team is at on the project. He also envisages that it will tie into national campaigns and health and safety weeks that will roll throughout the programme. The current thinking is that there will be at least four main stand downs every year project-wide in addition to individual site initiatives.

As an additional safety measure, the project team has decided to enforce a maximum shift length at any time of 10 hours. For those at the coalface, no one will be working more than eight hours at any one go, which means each site has “an hour pre-shift and an hour post-shift to completely prepare people to come to work healthy and safely and to go home equally as healthy and safe”.

One of the headline innovations on the Thames Tideway Tunnel is its immersive induction programme, part of which will be held at its purpose built employee project induction centre (EPIC). Much of what employees learn here will be reflected upon when the project is up and running and undertakes the regular stand downs.

“I have a very strong belief that if we truly want people to be part of a project or company, they have got to feel part of that,” Steve explains, on the thinking behind EPIC.

“The programme involves very early safety engagement (EaSE), so understanding exactly what our aspirations are, the things we are looking to achieve as part of the project, but more importantly it is to gain feedback from our teams very early on to help us shape and develop our programme based on their previous experiences.”

As Steve continues, part of the induction process includes a pre-employment screening to ensure that anyone subsequently employed is authorised to live and work in the UK. There is also a health screen to make sure that employees are fit for task, especially for safety critical roles.

“What we can’t do and are not prepared to do is put someone to work who is suffering from a pre-existing condition that we are likely to exacerbate,” he emphasises. “If that compromises his or her health and/or safety and health and/or safety of one of their colleagues, then we can’t let that happen.”

Another novel strand in the pre-induction process is the project’s mandatory health and safety communications assessment. The idea behind it is to prevent accidents that could be caused by workers that have a poor understanding of health and safety language.

“This is not a test of health and safety knowledge, and it is not a bar on being a non-English speaker,” stresses Steve. “It is in line with the common European framework for language. We have worked with colleagues at Loughborough and Glasgow universities to develop a common lexicon, language and visuals of standard health and safety communication.”

The prerequisite for attending EPIC is to undertake this mandatory test and successfully pass it. There are three levels – one for operative, one for supervisor and one for managers.

Successful candidates that pass the assessment and the pre-induction screening will then need to complete an online form before being invited, via EaSE 2, to attend EPIC to undertake this phase of the immersive induction programme. Steve describes it as being a very experiential and interactive health and safety, security and environmental induction; and to ensure that training is fully interactive, the project team has placed a cap on 36 inductees per session.

“[The day’s training] focuses on what happens when things go wrong, why they go wrong and what part we may or may not have had to play in what went wrong,” he explains.

The morning consists of a 90-minute session during which attendees will gain a clear understanding of what is expected of them at Thames Tideway Tunnel. Sessions include hazard spotting, and reporting and identification before moving on to cover leadership training.

“What we’ve found is that leadership training tends to be the preserve of senior and middle managers but in fact the true safety leaders are those individuals that make those tactical decisions day in, day out at the coalface,” he argues. “We never give them the softer skills to go and pinpoint and address unsafe acts and behaviours.”

At the end of the day, each employee will be issued with a project ID card, which matches their biometric hand comparison against their features and face. To ensure upmost security, the ID card will only enable the employee to access sites that they are authorised to visit.

A second full-day is currently being planned to take employees out on the river, so that they can gain a broader perspective of the project and the environmental benefits that it aims to deliver.

Taking the learning from EPIC and the full-day on the river, workers will then be assigned to the main works contractors to undertake their own site inductions to further enhance their training before starting work.

As Steve is keen to emphasise, occupational health and wellbeing is a core strand in the Thames Tideway Tunnel development. The project has adopted a four-pronged approach to health that broadly covers the workplace, the worker’s health, the worker’s wellbeing and the communities in which they will be working. In terms of the workplace, the emphasis is on prevention.

As Steve is keen to emphasise, occupational health and wellbeing is a core strand in the Thames Tideway Tunnel development. The project has adopted a four-pronged approach to health that broadly covers the workplace, the worker’s health, the worker’s wellbeing and the communities in which they will be working. In terms of the workplace, the emphasis is on prevention.

“Ergonomists and industrial hygienists, occupational health nurses and physiotherapists will sit with the design teams to design out those risks,” he argues.

“Where we can’t physically design out that risk, we will get them to design in suitable control measures, so that we can reduce to an absolute minimum the chance of people suffering either ill health or a safety-related injury at work.”

The focus on healthy workers goes back to the pre-employment screening, which is designed not only to ensure that workers are fit and healthy enough to work at Thames Tideway Tunnel but hopefully for the next project that they move on to afterwards.

Linked to this is worker wellbeing and Steve is adamant that the project will provide an extensive package of wellbeing activities to support workers when they are not working.

The final ‘health’ strand is where Thames Tideway Tunnel differs from other projects, he argues. Working in a congested construction environment, Steve points out that the project team is aware that workers may be exposed to health risks that are not directly related to the tunnel construction. The Vauxhall Nine Elms corridor is a case in point.

“It’s an understanding of what happens in the community around us and we’ve already started to undertake health risk assessments,” he explains.

“Health is not part of a generic risk assessment; we are doing specifically bespoke health assessments based on the work sites and more importantly the environment in which those work sites sit. Our pre-construction information already tells us and our main works contractors what we’re going to be coming up against, so we have a fairly good idea of how health is going to be impacted.”

While preliminary construction work is not scheduled to begin for another year, Steve has been kept busy finalising details on the project to ensure that when D-Day comes, it matches expectations.

“There is an unprecedented amount of construction activity in London as it is and we are going to add to this,” he concludes. “[But] we have a very clear aspiration of delivering a very transformational healthy and safe performance first time.”

Steve Howells is director of HSSE at Thames Tideway Tunnel and will present ‘Delivering the triple zero vision’ at 12.10pm in track A: Leadership in action, on Wednesday, 17 June.

The Safety Conversation Podcast: Listen now!

The Safety Conversation with SHP (previously the Safety and Health Podcast) aims to bring you the latest news, insights and legislation updates in the form of interviews, discussions and panel debates from leading figures within the profession.

Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts, subscribe and join the conversation today!

The Article has Definitely captured Steve’s passion and drive.