The tragic drowning of two brothers highlights the need to raise awareness of the precautions for safe working on inland waters. Alan Plom reports on notable prosecutions and suggests guidance that can help reduce the likelihood of similar accidents.

Last year, HSE brought a prosecution following the tragic death of two brothers on a wildlife lake. Both drowned in the incident. [1] The case re-emphasises the need for industry guidance and training that covers safe working on inland water in or from a boat.

Last year, HSE brought a prosecution following the tragic death of two brothers on a wildlife lake. Both drowned in the incident. [1] The case re-emphasises the need for industry guidance and training that covers safe working on inland water in or from a boat.

When we look at the latest figures from the National Water Safety Forum [2], it appears that in the UK in 2013, 381 people drowned in water from accidents or natural causes. Interestingly, HSE’s statistics reveal work-related incidents are very rare. However, the number and locations of ‘near-misses’ are not known and it is also difficult to find relevant advice on training and other precautions.

In the tragic incident of the two brothers, 17-year-old student Luke Yardy fell from a small boat while retrieving dead geese shot the previous evening as part of a cull on a wildlife lake at Wicken in Cambridgeshire.

His 22-year-old brother, Ashley, (who was not employed) was watching from the lake side and saw his brother get into difficulty. He swam out to rescue his brother but despite reaching him, they both drowned. The emergency services recovered their bodies a significant time later.

In the ensuing investigation, HSE found that the boat did not have a lifejacket on-board and the 17-year-old had not been trained in the use of the boat. The site was owned and managed on behalf of a trust by a local farming partnership, AC, PC, & RC Green.

The partners had engaged the student (as a ‘self-employed contractor’) and consequently were fined £60,000 and ordered to pay £31,252 in costs, after pleading guilty to breaching section 4(2) of the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974.

After the hearing, HSE inspector Peter Burns, said: “This was a tragic and wholly avoidable incident that has taken the lives of two loving brothers and devastated their family and friends. Had Luke been wearing a simple flotation aid, like a life jacket, then he would not have drowned, and Ashley would not have needed to attempt a rescue.”

It wasn’t the only incident in recent years to involve a tragedy involving water. In November 2011, a salmon farming company was fined £70,000 after a worker fell from a boat and drowned in 2008. [3]

The employee was one of five workers inspecting fish cages in a loch on the Isle of Lewis, when their boat filled with water and capsized.

HSE found that the risk assessments for workers travelling to and from the cages were not suitable or sufficient and that their employers had also failed to provide operating instructions for the safe use of the boat. The investigation also revealed that the boat had been overloaded; the manufacturer’s recommended maximum of three people was regularly exceeded. What’s more, although the company had provided a range of buoyancy equipment, it had failed to issue clear advice and instructions on how to use it, “causing confusion among staff”.

While the advice that follows applies to specific work activities, it can also be used to improve safety in other sectors, i.e. wherever work is carried out from boats, e.g, maintaining lakes or waterways, as well as occasional emergency work such as following flooding.

HSE’s agriculture information sheet AIS1, Personal buoyancy equipment on inland and inshore waters [4] highlights that accidental drowning can usually be linked to one or more of the following factors:

- failure to provide (suitable) personal buoyancy equipment;

- failure of buoyancy equipment to operate correctly;

- disregard or misjudgement of a hazard;

- lack of supervision, especially of the young;

- inability to cope once a problem arises;

- the absence of rescuers and rescue equipment;

- failure to take account of weather forecasts;

- falling unexpectedly, fully clothed into cold water,

- trying to swim or co-operate with rescuers is often extremely difficult and even strong swimmers may experience problems.

Sources of guidance

AIS1 is aimed specifically at fish farms. However, the guidance contained in it is also relevant to other water-borne work activities. In addition to outlining the legal requirements, the information sheet advises that where there is a foreseeable risk of drowning (not controlled by other means), then suitable personal buoyancy equipment needs to be provided, and worn. The document also gives detailed advice on selecting, using and maintaining these.

The Association of Inland Navigation Authorities (AINA) Good practice guide [5] gives comprehensive guidance on ‘managing inland waterway safety risks’ for visitors and workers but no detail (in its 43) pages on actual precautions and the nature of training required.

The Maritime and Coastguard Agency’s code of practice, The safety of small workboats and pilot boats, [6] is another useful resource and provides more guidance on the provision, correct fitting, maintenance and use of lifejackets. This code of practice also advises that training should be given on the procedures for rescuing people from water (including rescue into a boat).

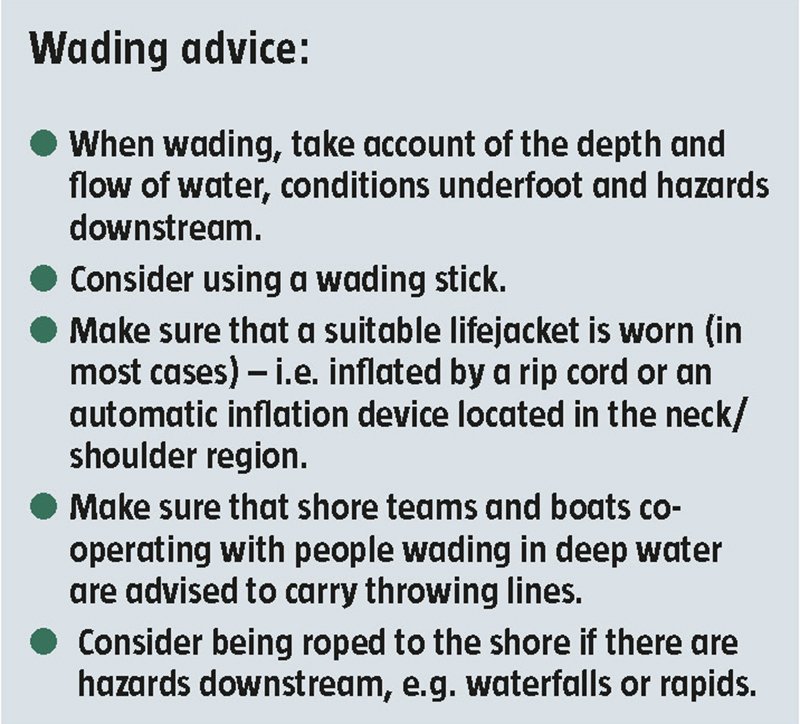

Another HSE guidance document that specifically refers to working on water is INDG 177: Gamekeeping and deer farming – a guide to safe working [7]. Also relevant to anyone that works in a ‘water-based’ environment, INDG 177 includes sound practical advice on ‘personal fitness’ and general ‘suitability for the work’, as well as guidance on working in boats and the selection of lifejackets. It also describes precautions when wading in water, which would also be relevant to many activities, e.g. research and conservation projects, as well as local authorities and others maintaining ponds and lakes, etc. (see wading box).

Another HSE guidance document that specifically refers to working on water is INDG 177: Gamekeeping and deer farming – a guide to safe working [7]. Also relevant to anyone that works in a ‘water-based’ environment, INDG 177 includes sound practical advice on ‘personal fitness’ and general ‘suitability for the work’, as well as guidance on working in boats and the selection of lifejackets. It also describes precautions when wading in water, which would also be relevant to many activities, e.g. research and conservation projects, as well as local authorities and others maintaining ponds and lakes, etc. (see wading box).

Michael Cusack’s online SHP article, “Inland water hazards are often overlooked” [8] outlines the key determiners that will affect a person’s chance of survival should they fall into water, be it a fast flowing river or a deep reservoir. It is important to stress here that selection of suitable personal protective equipment (PPE), the impact of water temperature, the ability to swim and an understanding of defensive swimming, as well as level of fitness, are all critical.

The original British Waterways’ Code of practice for Third Party Works’ Procedures (Section 2, 2012) [9] points out that the risk of drowning is less than that of the shock of falling into the water, particularly in cold conditions, which can cause heart spasm. It also advises that dragging oneself out of even shallow water when cold and wet can be energy sapping, particularly if you are some distance away from welfare facilities. Michael Cusack’s article also highlighted that 55 per cent of all deaths from drowning take place within only three metres of safe refuge.

‘Grab and throw lines’ for rescue

HSE’s Health and Safety in Construction (HSG 150) [10] features a section that explains how people working beside or above water, or passing near or across it on their way to or from their workplace, can avoid falling into the water and potentially drowning (see pp 102-3).

The document provides useful guidance on ‘safety’ lines and rescue procedures. It advises that a grab line can be hung across a river downstream of the work site to act as a safety feature. This should be tensioned across the river so that it runs at 45 degrees to the flow, with the most downstream end to the bank from which easiest access can be made. Not being hung at 90 degrees allows the swimmer to be washed to the downstream end as they hit the line.

Conversely, a throw line should not be tied to anything. For use in moving water, the rope needs to be 8-12 mm diameter for ease of handling, brightly coloured and able to float (to avoid entanglement on the river bed). If the force is too much to hold, the rescuer holding the rope should walk down the bank, recovering or releasing the line so as to prevent the rescuer from being pulled into the river. A tied or snagged line may have the effect of submerging the person in the water if the current is fast.

A handful of universities have also issued and posted comprehensive internal guidance for their students on the use of small workboats. For example, the University of St Andrews [11] and others (such as the Institute of Aquaculture at Stirling University and Nottingham University’s school of geography) have provided similar guidance on hazard and risk assessment for students carrying out fieldwork.

Most are based on the Natural Environment Research Council’s 1997 guidance, Safety in Fieldwork, [12] and the Department of Transport’s A Guide for Small Boat Users. The Transport Department’s document provides a long check-list that covers the essential precautions for the safe use of small craft.

These include making sure that:

- The craft is suitable for the job, is in a good state of repair/‘seaworthy’ and its capabilities are known, e.g. carrying capacity.

- The crew has up-to-date information on tidal races, rocks, obstacles or other local hazards that are likely to be encountered.

- Everyone wears a personal flotation suit, lifejacket or approved buoyancy aid. [Note: no single type of lifejacket is ideal for every task.]

- The requisite safety equipment and emergency kit is on-board, including an anchor; bailer; bellows or inflator and repair kit for inflatables; boathook, paddle (for motorised craft) or oars; crew know where it is stowed and how to use it in an emergency.

- Clothing must never be worn outside a self-inflating lifejacket.

- Boats should only be handled by authorised persons. [Note: some appoint a ‘boat maintenance officer’ ‘to take responsibility for the routine maintenance of the boat and associated equipment’.]

- The crew keep a record of use, including hours, fuel used and any incidents affecting the boat or its engine.

Training

Basic skills training in how to operate small craft on inland waterways is available through local sailing clubs, usually affiliated to the Royal Yacht Association (RYA). [13] In Ireland, training and certification is controlled by the Irish Sailing Association (ISA). [14]

Both of their websites contain summaries of training, and readers would be advised to approach their local club or training provider to develop a bespoke course. Remember that an integral part of the training should consider the typical locations, practical applications and work activities being carried out from a boat, as well as awareness of the appropriate precautions, including selection and use of PPE, and rescue procedures. Supervisors should also be familiar with safe practices and monitor compliance during operations.

Ireland’s HSA recently published Managing Health and Safety in Fishing (HSA0428) [15], which contains useful guidance on ‘competence’ and the provision of ‘adequate information, instruction, training and supervision’.

The Emergency Services and other organisations regularly ‘working on water’ from boats will obviously be providing training for their own staff.

Alan Plom would be interested to hear from readers that are aware of any other relevant guidance or sources of suitable training that could improve safety more widely. Email Alan at: [email protected]

Alan Plom would be interested to hear from readers that are aware of any other relevant guidance or sources of suitable training that could improve safety more widely. Email Alan at: [email protected]

Alan Plom is an independent self-employed consultant/trainer working in the land-based and local authority sector and is Vice Chair of IOSH Rural Industries Group

References

- http://press.hse.gov.uk/2014/cambridgeshire-farming-firm-in-court-following-wetland-deaths/?ebul=hsegen&cr=3/17-feb-14

- nationalwatersafety.wordpress.com/

- hse.gov.uk/press/2011/coi-sco-10311.htm

- hse.gov.uk/pubns/ais1.pdf

- http://www.aina.org.uk/docs/good%20practice%20guides/Navigationsafety2013%20final.pdf

- gov.uk/government/publications/small-craft-codes

- hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg177.htm

- shponline.co.uk/inland-waters-overlooked-hazards/

- britishwaterways.co.uk/media/documents/foi/technical/Code-of-practice-Section-2-Code-of-Practice-03-2012.pdf

- hse.gov.uk/pUbns/priced/hsg150.pdf

- st-andrews.ac.uk/staff/policy/healthandsafety/publications/boats-useofsmallworkboats/

- www.nerc.ac.uk/about/policy/safety/procedures/guidance_fieldwork.pdf

- rya.org.uk/startboating/Pages/InlandWaterways.aspx

- sailing.ie/Training/SeabasedTrainingCourses/InlandWaterways.aspx

- hsa.ie/eng/Publications_and_Forms/Publications/Fishing/Managing_Health_and_Safety_in_Fishing.html

The Safety Conversation Podcast: Listen now!

The Safety Conversation with SHP (previously the Safety and Health Podcast) aims to bring you the latest news, insights and legislation updates in the form of interviews, discussions and panel debates from leading figures within the profession.

Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts, subscribe and join the conversation today!