How probabilities combine to determine the outcome of an event

By Phil Chambers BSc, CMIOSH

Safety professionals should be aware of the Bird Triangle, which shows that if you have enough incidents, then eventually you will have a serious injury. Some people have proposed a model of slices of Swiss cheese where the holes line up, and an excellent article by Neil Budworth in SHP in March 2013 talked about near miss data. However, nobody, to my knowledge has properly explained why the Bird Triangle should be so.

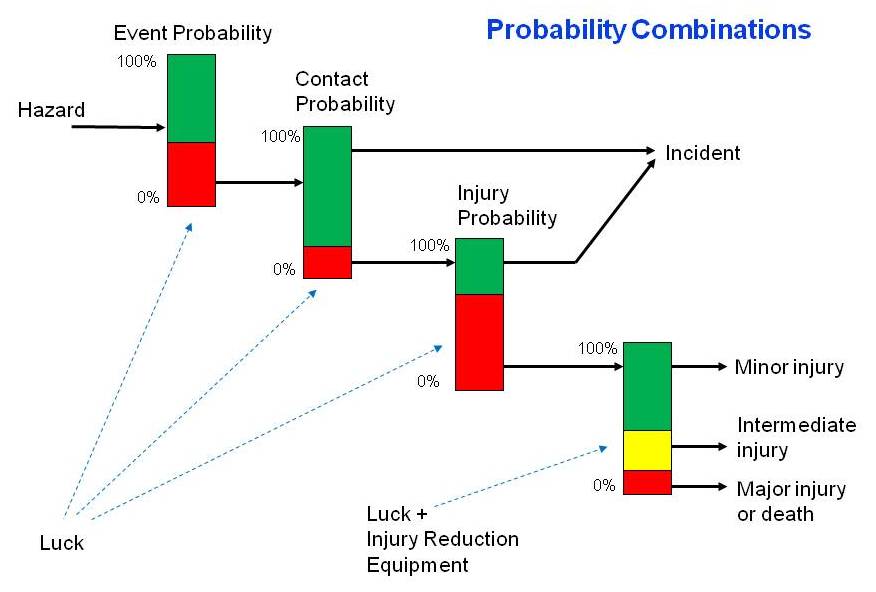

The model I show below is based on probabilities, ranging from 0 (will never happen) to 100% (will happen every time) and shows what determines the different outcomes.

You could use 0 to 1 which makes it easier to multiply the different probabilities.

If we have a hazard, then there is some probability that is will lead to an event. I have shown this as either red or green. If there is an event (the red part), then there is the probability that someone or something will be in the way and contact occurs. If contact occurs, then there is a probability of it being a glancing blow or one which causes injury. If an injury occurs, then there are probabilities of the severity of the injury. With the weightings of this diagram, we have something like a probability of 40% x 20% x 60% x 15% (ie 6%) of death.

With the majority of these, we have no control over the probability; it is pure luck. The only probability we can affect is that of injury, where the use of PPE, seat belts, etc., reduces the outcome. They do not affect the likelihood of injury, just its severity.

An example to which we can all relate is a hazard caused by defective tyres on a car. There is the probability of, say a skid or blowout, followed by the probability of another vehicle or fixed object being hit. The probabilities of any injury and its severity are determined by the speed, plus the injury reduction devices such as crumple zones, seat belts and airbags. Of course, if the object hit is a pedestrian or cyclist, then their injury reduction equipment is non-existent.

What this model should lead us to do is:

1. To reduce hazards so far as is reasonably practical using risk assessment and employee hazard reporting

2. To regard incidents or near misses as being the same as an accident.

3. To regard minor injuries as seriously as major injuries in circumstances where luck determines the outcome.

All action management systems (I’ll talk about these in a later article) should have the ability to record whether something was 1], 2] or 3] and to provide counts of these for management information. Good safety control is where you have a high count of 1], a lower count of 2] and a very low count of 3].

How probabilities combine to determine the outcome of an event

Safety professionals should be aware of the Bird Triangle, which shows that if you have enough incidents, then eventually you will have a serious injury. However, nobody, to my knowledge has properly explained why the Bird Triangle should be so.

Safety & Health Practitioner

SHP - Health and Safety News, Legislation, PPE, CPD and Resources Related Topics

Workers facing uncertain future coupled with health and safety risks, new IOSH report says

Legionella Management: Who can be appointed as RP, DRP, AP or CP?

James Macpherson on risk: ‘More of the same won’t work’