Credit: Flickr via Eric Schmuttenmaer

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders are on the rise despite a wealth of training and information being readily accessible, argues Liz Burton, High Speed Training.

Despite the fact that information and training on preventing chronic injuries is readily accessible nowadays, year after year we are still seeing a disconcerting rise in cases of work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

Although not life threatening, both episodic and chronic cases significantly reduce a person’s quality of life, and currently affect a sizeable portion of the population. According to the HSE, the total number of work-related musculoskeletal disorder cases in 2014/15 was 553,000 and the number of new cases was 169,000.

Transportation and storage, health and social care, agriculture, and construction industries have the highest rates of work-related musculoskeletal disorders, but less obvious industries such as cleaning and office work are also at risk. When organisations in these industries establish their health and safety policy, musculoskeletal disorder risks must be taken into account.

What puts those working in cleaning at risk of MSDs?

As the HSE highlights, cleaning work is demanding and labour-intensive. Tasks involving cleaning machinery and heavy manual work – e.g. mopping, wiping, hoovering, carrying bags of waste, and moving furniture – can lead to MSDs if not carried out ergonomically.

A document published by the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work states that in a survey of interiors cleaners, 74% reported experiencing muscular aches, pains, and discomfort in the past year. The main areas affected were the lower back (46%), neck (33%), knees (24%), right shoulder (23%), and right wrist/hand (22%).

There are six particular ergonomic risk factors relating to cleaning:

- Working in awkward postures – e.g. twisting and leaning over a kitchen counter to wipe the surface or having to bend forward when mopping or hoovering.

- Excessive force – cleaning roles require a great deal of ‘elbow grease’ to thoroughly scrub and wipe surfaces, which places strain on joints and muscles.

- Contact stress – areas of the body may undergo stress when placed against another surface, e.g. wrists, hands, and arms against a countertop.

- Manual handling – part of a cleaner’s role may involve handling furniture, work equipment, rubbish bags, or boxes. If not carried out correctly, undue strain may be placed on limbs, joints, shoulders, and the back.

- Vibration – cleaning machinery may emit high levels of vibration, which when used often and for prolonged periods can lead to numbness in limbs and neurological disorders in hands and arms (e.g. carpal tunnel or white fingers).

- Repetitive movements – scrubbing, mopping, and hoovering requires strenuous, repetitive back-and-forth motions that are harmful to the body in excess and if not carried out ergonomically.

Another risk factor includes cleaners having to work in buildings not designed to be ergonomically-friendly for their job role. Spaces that need cleaning may even be confined, e.g. a small bathroom cubicle or public transport, which restricts ergonomic cleaning.

Furthermore, cleaning equipment may not be ergonomically designed. Qualities that help reduce strain include:

- Adjustable handles – the user can set the equipment to a suitable height.

- Comfortable grip handles – reduces vibration and encourages the correct positioning of hands.

- Bent handles – minimises the force and leverage required to move the equipment.

- Swivel handles – enables equipment to be used with minimal wrist strain.

- Low drag design – reduces the amount of force required to push and pull.

- Low centre of gravity – makes equipment such as Hoovers feel less weighty and therefore less strenuous to manoeuvre.

- Lightweight extension poles – users can reach further with it, which reduces strain.

Taking these factors into consideration will help cleaners reduce the growing issue of musculoskeletal disorders. The document published by the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work provides more useful information on cleaners and musculoskeletal disorders.

There is also an opposite extreme to the strenuous job role of cleaning: PC users who have to sit statically for the majority of the day. This role carries an equal degree of risk.

What puts those working with display screen equipment (DSE) at risk of MSDs?

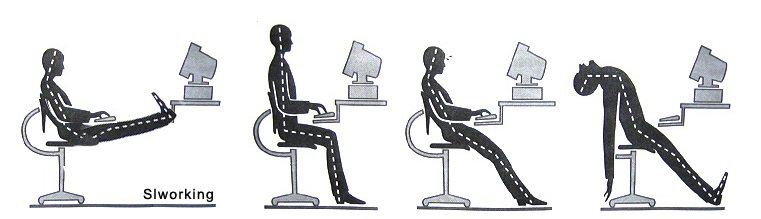

The human body is not designed to sit for excessive periods of time. In occupations that require using computers, this is difficult to avoid. The layout of equipment and the user’s posture are factors that should be taken into account so to minimise the risk of developing MSDs when using DSE.

There are six particular ergonomic risk factors:

- Position of monitor – if the height and orientation of the monitor are not ergonomic, strain will be placed on the neck.

- The work surface – those that lack space will cause people to adopt awkward positions that lead to stiffness and fatigue in joints.

- Keyboard position – strain on wrists and forearms will occur if keyboards aren’t positioned correctly, leading to repetitive strain disorders such as carpal tunnel.

- Mouse position – having to overreach for a mouse or holding it too close to the body places undue strain on the wrists and forearms.

- Chair design – without a chair that has sufficient back and rear support, users may not be seated with good posture and strain will be placed on the upper and lower back.

- User posture – ultimately users need to be responsible and adopt a good posture, i.e. sitting up properly, not twisting the neck or shoulders, and not crossing legs.

DSE users should be trained in the proper usage of their equipment and good posture. Organisations might consider displaying a desk ergonomics diagram somewhere that’s visible to everyone in the workplace or incorporating it in the health and safety policy.

The rise of musculoskeletal disorders is unlikely to dissipate overnight, but spreading awareness of how to minimise risk will make a difference in the long-term.

Given that MSDs develop overtime, we are likely to continue seeing new cases even when the majority of workplaces have systems in place for preventing them; many people will have already been irreversibly affected by previous experiences.

But if organisations take action right now to reduce the strain placed on people’s bodies whilst working, they will yield long-term improvements that see people are MSD-free, even after several years of working in high-risk roles.

Liz Burton is a Content Author at High Speed Training: a UK-based online learning provider that offer training courses, including Manual Handling training and Display Screen Equipment training. Liz has authored many courses, including the DSE Assessor training course, and numerous articles on topics relating to musculoskeletal disorders for HST’s blog, the Hub.

Approaches to managing the risks associated Musculoskeletal disorders

In this episode of the Safety & Health Podcast, we hear from Matt Birtles, Principal Ergonomics Consultant at HSE’s Science and Research Centre, about the different approaches to managing the risks associated with Musculoskeletal disorders.

Matt, an ergonomics and human factors expert, shares his thoughts on why MSDs are important, the various prevalent rates across the UK, what you can do within your own organisation and the Risk Management process surrounding MSD’s.

Mmm still, missing the point that SCREEN FATIGUE is the driver in the chain of causation of initially debilitating symptoms of over-exposure to a stressor that results, over time, in any RSI type injury. Human Beings natural survival systems will seek to make, reasonably well meaning, adaptations to build resilience to a physical and/or mental stressor lasting longer than 90 minutes (point of fatigue) and the cycle of coping, tolerance and adaptation will continue until the human organism runs out of adaptations yet, the individual will often persevere regardless, for whatever reason, choosing to ignore the warning signs, discomfort and/or… Read more »