There have been cases where highly experienced and trained workers with impeccable safety records have died at work because they momentarily lost concentration or acted out of character. We asked Dr Tim Marsh what employers can do to prevent fatalities like this.

Catastrophic incidents happen to safety conscious people for the same reason that some children will be pulled alive from the wreckage of a collapsed building. It is the law of probability.

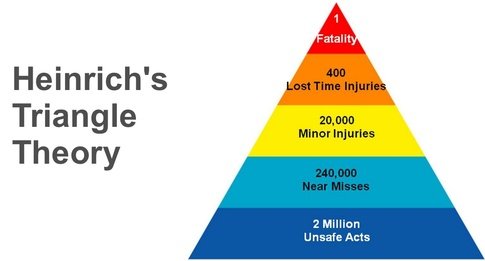

On any given day, in any given situation, some people will be lucky and some will not. However, while we can’t ensure good luck, we can significantly impact on how much luck we need. This requires a consideration of the nature of risk, risk literacy and a defence of the underlying principle of Heinrich’s accident triangle.

Heinrich’s Accident Triangle

Heinrich’s accident triangle has received some criticism recently but the basic principle that underpins it remains sound. Gary Player famously quipped: “Isn’t it funny how the harder I practise the luckier I seem to get?” which is the main point of every inspirational ‘maximise your potential’ speaker you’ll ever hear.

Let’s say that the odds of falling for a person that is working at height (and is momentarily distracted while not clipped on) are 100,000 to 1. If this applies to 10,000 workers once a week, then we will lose five workers every year — give or take. The wider the bottom of the triangle is, the wider the sharp, top part is.

Conversely, it’s also true that the narrower the bottom of the triangle, the narrower the top will be. Either way, it’s far easier to predict numbers than names.

If we do lose five workers in this way, then over a 10-year-period, the majority will most probably come from those who take the most chances, but two or three will be those who took very few.

Working at height is really dangerous and always will be. With ‘line of fire’ incidents the principle is much the same. Sooner or later something will fail, shift or drop.

Heinrich’s Accident Triangle: Safety Talk by Tim Marsh

Health and safety hierarchy

In one respect, experience doesn’t necessarily help either. Fear provides adrenaline and alertness, directs attention and focuses the mind. However, years of working in an environment (as the job becomes second nature) will reduce the sense of fear.

Although we can, and should, encourage employees to always be on their guard, this has an upper limit because of the limitations on concentration. It varies depending on the task at hand, but on average we can concentrate for around 55 minutes an hour when rested and well.

Tired, off colour, stressed, hungover or just a little over-confident and it’s likely to be worse. If we return to our population of 10,000 workers at height (those who interact with dangerous plant or equipment) for an hour a week each, then that zombie time adds up to around 480,000 hours a year.

Some will argue that training these people in what’s known as ‘situational awareness’ skills will help. Alternatively, we may give them some inspirational and/or high impact person-focused input — sometimes claimed to be ‘advanced behavioural safety’ — where we seek to embed a key motivational image like our children at our funeral. These can be helpful for average workers (ideally as part of a holistic package and to supplement an analysis focus) but are really of little use to those who are already experienced, conscientious and motivated.

A much better strategy is to constantly try and move the task up the safety hierarchy by designing out the risk. This might involve foolproof fall arrest technology that never needs unclipping. It might mean replacing all windows at height with the self-cleaning kind. Instead of reminding workers to “be careful not to stand there” whenever possible, we must make it impossible to stand in a dangerous position.

In some cases a design solution is not possible but we should always be looking for one and never allow ourselves to get comfortable with a ‘standard risk’. The mindset that it’s just the nature of the beast is the enemy of the creative design that underpins continuous improvement.

An excellent example of this comes from Formula One where the received wisdom was that the occasional death went with the territory. Forty-seven drivers had been killed in 44 years until San Marino in 1994 when both Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna died on consecutive days. Rubens Barrichello very nearly died the day before.

When a traumatised Max Mosley announced: “This simply cannot happen again”, many in the industry were sceptical about such a bold statement. But by insisting that teams apply their skill and ingenuity to safety as much as to speed (and then share innovations) a massive shift in safety culture was achieved. As the 2013 season came to an end, no deaths were reported.

This leads to Heinrich’s principle (not his data) and the need to defend two criticisms of his triangle.

Heinrich, behaviour and the unions

Pro-actively working the bottom of Heinrich’s triangle means behaviour (traditionally workforce behaviour). We all know that a conversation that starts: “Can I talk to you about your behaviour?” rarely ends well. Somehow this negativity by association has morphed into a general (and, at times, bizarre) attack on Heinrich.

Simplistic ‘culture’ programmes work from the principle that, since our culture is in essence “the way we do things around here”, then a focus on behaviour is a culture change programme.

However, we shouldn’t just focus on PPE, trip and fall hazards and line of fire issues. We should also cover supervisor behaviours such as toolbox talks (are they a mumbled nonsense that neither teaches nor inspires?) and board level strategy meetings.

Previous articles on Reason’s Cheese model and Just Culture have stressed that a behavioural approach must be based on these high-level decisions and behaviours first and foremost.1 Many are not, however, and even the most well-meaning observation and intervention-based behavioural programmes can irk workforce representatives.

The famous ‘one minute manager’ stresses how we must get out and about and ‘catch a person doing something right’ to give praise, reinforce and embed the behaviour at hand. That’s great as part of a holistic approach, systemically involving analysis, involvement, facilitation, design and coaching before we focus on the person.

However, if used as a standalone and we get the tone slightly wrong, it’s not hard to recall that the roots of classical conditioning start with Pavlov and his dogs — “sit, wait, roll-over€ᆭ good boy”.

The reasonable response to this is: “I can see you have my best interests at heart” but it’s a little patronising at times. The more robust response is to accuse management of manipulation and ‘mind games’. Add the entirely person-focused ‘hot-coal’ merchants to these approaches and it’s very easy to see why a head of indignation has built up.

However, it is not uncommon to hear the expression “roots in fascism” used as an attack on behavioural safety. It perhaps refers to the fact that Heinrich was rather right wing in his day.

Regardless of his politics, it is clear that Heinrich did know his safety hierarchy, as demonstrated by this quote: “No matter how strongly the statistical records emphasise personal faults or how imperatively the need for educational activity is shown, no safety procedure is complete or satisfactory that does not provide for the€ᆭ correction or elimination of€ᆭ physical hazards”. Indeed, emphasising this aspect of workplace safety, Heinrich devoted 100 pages of his classic work to the subject of machine guarding.

As unions often say, a key reason even conscientious, safety conscious and experienced workers come to harm is because they work in a culture where management focus only on workforce behaviour and spend their efforts encouraging the workforce to ‘be careful’ rather than analyse the cause of the behaviour so they can design out the risk.

Heinrich’s Accident Triangle and process safety

A number of articles have been critical of Heinrich, especially in relation to process safety. Lynn Dunlop in ‘Beyond the Safety Triangle’ quotes Andrew Hale as saying, “We are not going to get very far in preventing chemical industry disasters by encouraging people to hold the handrail when walking down the stairs”.2 It’s a great quip but whoever suggested we would?

We are never going to get close to being lost time injury (LTI)-free either without a focus on handrail holding, as typically a third of accidents (or more) at any site are falls. BP at Texas City didn’t have an active strategy to keep process safety under control through a low LTI rate; they simply sleep walked into a vulnerable position because they took undue reassurance from strong personal safety scores. That’s just a lack of holistic risk literacy.

Again quoting Hale: “A large release of flammable chemicals will€ᆭ produce more fatalities than objects dropped from scaffolding€ᆭ at this level of cause there is only a very limited overlap between major and minor injuries.” The implication of this line of reasoning is far too black and white and is focused on the wrong level of cause.

Perhaps the major cause of Piper Alpha was that the permits were signed off blindly. However, offshore permits ask for confirmation that housekeeping be acceptable before they can be submitted, so any analysis of the (notoriously poor) housekeeping would have taken investigators straight to a weakness in the permit system. A weak or patchy safety culture is a weak or patchy safety culture and all the various ways it manifests itself come from the same primary source.

In his study of Texas City, Andrew Hopkins described a culture in which only good news is allowed to travel up.3 Cuts were forced through and assurance was taken from the fact that LTI rates remained low even as the infrastructure crumbled and degraded around them.

The behavioural safety team at Texas City didn’t cause the explosion — the culture of aggressive cost cutting, sloppy thinking and poor listening did. That came from the very top.

Only the day before the Macondo explosion in the Gulf of Mexico, there was an infamous VIP walk around the site that covered a fall from height issue thoroughly. Again, this conversation didn’t cause the explosion, it was that the VIPs skipped straight past the critical process safety issues about pressure readings with an “Everything OK?” question that allowed for a “Yes, boss” response.

The safety culture was extremely strong in many respects, but there was a blind spot regarding process safety caused by an absence of incentive levers (present for production and personal safety). The mindset was that robust questions about process issues suggested a lack of trust (it ‘just wasn’t done’ — which is the very definition of a culture).

Hopkins goes on to suggest that it makes no sense for experienced managers to chat only about personal safety issues and not take the opportunity to ‘deep dive’ into process safety issues while out there.4

The basic Heinrich (or Gary Player) principle still holds. Halving the number of poor handovers, weak communications, simplistic decisions or mindless ‘tick box and file’ audits will reduce the number of process safety incidents, big and small. In-depth, analytic conversations are much harder than hardhat head counts and that’s why they happen less often. It takes more effort.

Anyone that suggests their data doesn’t support the above position is collecting the wrong data and/or collecting inaccurate data.

Drilling ‘kicks’ are a good example: on the Deepwater incident, though personal safety was very well monitored, nobody was really monitoring the likelihood of a blow out. No one even reacted effectively when it started to actually happen.5

Again, in ‘Mysterious Ways’ (SHP August 2013), I stressed that perhaps the very definition of a strong safety culture is the speed with which it reacts to contain the risk or rectify the problem when something goes wrong.

In hindsight, it’s alarming that few oil companies collected data either about the number of ‘kicks’ they experienced or the speed with which they are spotted.

Personal safety is hugely important, but of course we shouldn’t be counting hard hats in preference to monitoring kicks, so again this isn’t a case of Heinrich and behavioural safety or process safety. The basic underpinning principles (with Heinrich’s principle to the fore) remain the same. Analyse and act.

References

Marsh, T. (2013) “Mysterious Ways”. SHP August.

Dunlop, L., (2013) “Beyond the Safety Triangle”. SHP October.

Hopkins, A. (2008). “Failure to Learn”. CCH Australia.

Hopkins, A. (2012). “Disastrous Decisions”. CCH Australia.

Marsh, T. (2013) “Mysterious Ways”. SHP August.

Dr Tim Marsh is managing director of Ryder-Marsh Safety Ltd

Heinrich’s Accident Triangle CPD Quiz

Continuing professional development is the process by which OSH practitioners maintain, develop and improve their skills and knowledge. IOSH CPD is very flexible in its approach to the ways in which CPD can be accrued, and one way is by reflecting on what you have learnt from the information you receive in your professional magazine. By answering the questions below, practitioners can award themselves credits. One, two or three credits can be awarded, depending on what has been learnt — exactly how many you award yourself is up to you, once you have reflected and taken part in the quiz.

There are ten questions in all, and the answers can be found at the end of this article. Learn more about

CPD and the IOSH approach.

QUESTIONS

1 A reason that some safety conscious people still suffer accidents is because:

a) They don’t follow safety rules

b) They are too preoccupied with safety

c) Luck — the law of probability

d) They have variable levels of experience

2 If the chance of a fatality from a fall from height is say 1 in 100,000, then among 10,000 people working at height every week, statistically the number of fatalities per year would be in the order of:

a) 1

b) 5

c) 1,000

d) 500

3 On average, a person in good health and composure can concentrate for:

a) 10 minutes in every hour

b) 30 minutes in every hour

c) 8 hours in every 24 hours

d) 55 minutes in every hour

4 An effective way of making a task safer is:

a) Reminding people to work safely more often

b) Disciplining people who do not work safely

c) Re-designing the task or equipment to remove or reduce the risk

d) Giving the task to contractors to carry out

5 An effective culture improvement programme would include the following two factors:

a) Focuses solely on hazards and protective measures

b) Includes the behaviour of supervisors

c) Includes constantly confronting people about their behaviour

d) Includes behaviour at senior management level

6 Andrew Hopkins has ascribed the following two factors as causes for the Texas City disaster:

a) A high rate of lost time injuries

b) Poor personal safety scores

c) Aggressive cost-cutting

d) Senior management’s failure to listen effectively to the workforce

7 Hopkins also concluded that the missing area of scrutiny in the case of the Macondo explosion was:

a) Production issues

b) Personal safety among operators

c) Lost time accidents

d) Process safety

8 The definition of a strong safety culture could be said to be:

a) An abundance of safety rules

b) The amount of experience that people have

c) The speed at which it reacts to contain or rectify risks

d) Where a high number of inspections are carried out

9 A major cause of the Piper Alpha disaster could be said to be:

a) Permits were signed off blindly

b) Permits did not consider housekeeping issues

c) No permits were issued

d) Permits got lost

10 A higher number of events on the base of the Heinrich triangle will result in:

a) A smaller number of serious accidents

b) A higher number of serious accidents

c) No effect on the number of serious accidents

d) A need to reduce the amount of data collected

Answers

1) c

2) b

3) d

4) c

5) b, d

6) c, d

7) d

8) c

9) a

10) b

Advance your career in health and safety

Browse hundreds of jobs in health and safety, brought to you by SHP4Jobs, and take your next steps as a consultant, health and safety officer, environmental advisor, health and wellbeing manager and more.

Or, if you’re a recruiter, post jobs and use our database to discover the most qualified candidates.

Continuing professional development is the process by which OSH practitioners maintain, develop and improve their skills and knowledge. IOSH CPD is very flexible in its approach to the ways in which CPD can be accrued, and one way is by reflecting on what you have learnt from the information you receive in your professional magazine. By answering the questions below, practitioners can award themselves credits. One, two or three credits can be awarded, depending on what has been learnt — exactly how many you award yourself is up to you, once you have reflected and taken part in the quiz.

Continuing professional development is the process by which OSH practitioners maintain, develop and improve their skills and knowledge. IOSH CPD is very flexible in its approach to the ways in which CPD can be accrued, and one way is by reflecting on what you have learnt from the information you receive in your professional magazine. By answering the questions below, practitioners can award themselves credits. One, two or three credits can be awarded, depending on what has been learnt — exactly how many you award yourself is up to you, once you have reflected and taken part in the quiz.

Excellent piece and some great research work for the article. Really helpful and thought provoking.

Very useful and thought provoking.

Agree, very good article. I have just finished reading Dr Marsh’s book ‘Talking Safety’ and really like his clarity of expression.

As always, Tim Marsh is thought provoking, informative and right.

Good Article, outlines some good points and gives support to the triangle theory.

The article was excellent and I very much enjoyed reading it as it covers areas of my past research. I believe the key thing about Heinrich’s accident triangle is that it applies to apples and it applies to pears but the data should not be automatically used to mutually inform. The research was conducted for the UK nuclear power industry via DNV with a colleague.It addressed the question of whether occupational H&S and plant safety were related? Email me iandalling@a b.com for report.

Excellent ,well informatrive and a very useful article . I impressed myself 10 out of 10

Very informative and certainly got me thinking . I certainly will be getting the talking safely book .

Tim Marsh strikes again. Well written, concise and makes an awful lot of sense.

Very good article and CPD quiz.

I enjoyed the aticle and found it to be interesting and thought provoking.

A very good article which does get you thinking

Excellent article!

This article was very interesting and very informative. Great

I found this article very insightful and very interesting

A well balanced & informative article. I actually got 3 of the questions wrong so had to read again!..

[…] For every near miss that’s not investigated or reported, it’s more likely there’ll be an accident. For every minor accident that’s not reported or investigated, it’s more likely there’ll be a major accident, and so on and so forth. This principle is commonly referred to as Heinrich’s Accident Triangle, which you can find out more about in an interesting article from SHP. […]

simply the best so far