4. Why was there an apparent deficiency in firefighting equipment?

While initial analysis in the wake of the fire focused on cladding, firefighting equipment has come under the spotlight in recent days. A BBC Newsnight investigation uncovered multiple deficiencies, including that a high ladder did not arrive for more than 30 minutes.

Also known as an ‘aerial’, the ladder would have given firefighters a better chance of extinguishing the blaze had it arrived earlier, a fire expert told the BBC.

Are cuts to the fire service to blame for the shortcomings in firefighting equipment? Or is the problem more organisational and procedural?

Matt Wrack, general secretary of the Fire Brigades Union, said: “I have spoken to aerial appliance operators in London […] who attended that incident, who think that having that on the first attendance might have made a difference, because it allows you to operate a very powerful water tower from outside the building onto the building.”

Low water pressure was also said to hamper efforts to quell the flames, while firefighters reported radio problems.

Are cuts to the fire service to blame for the shortcomings in firefighting equipment? Or is the problem more organisational and procedural? Perhaps the UK’s comparatively – and deceptively – strong fire safety record had simply bred complacency in making sure enough equipment was available.

Find out more on the BBC.

5. Should COBRA have been convened in the wake of the fire – as it is following terror attacks?

Stephen Mackenzie, a fire risk consultant who has spoken out on the Grenfell fire regularly in the media, believes the UK’s worst-ever tower block fire warranted the most serious government response. “I think we’ve seen a comparison between the Grenfell fire and Finsbury Park terrorist attack,” he notes. “Immediately following the Finsbury Park attack, Theresa May convened COBRA.

“That should have been the case on Thursday [the day after the fire], [or] the latter hours of Wednesday. Convene COBRA, get emergency personnel leads in, coordinate with local authority responders, and have a better response and management of media, and [to] the families’ and residents’ concerns.

“I feel it could have been sharper, more effective, and then the central government may not have received some of the criticism it has.”

He adds that “there are a number of professional bodies in the UK that can facilitate” the transition “from the emergency services response into the softer response by local authorities and the government. So it might be another line of enquiry for the coroner report, and also the public inquiry.”

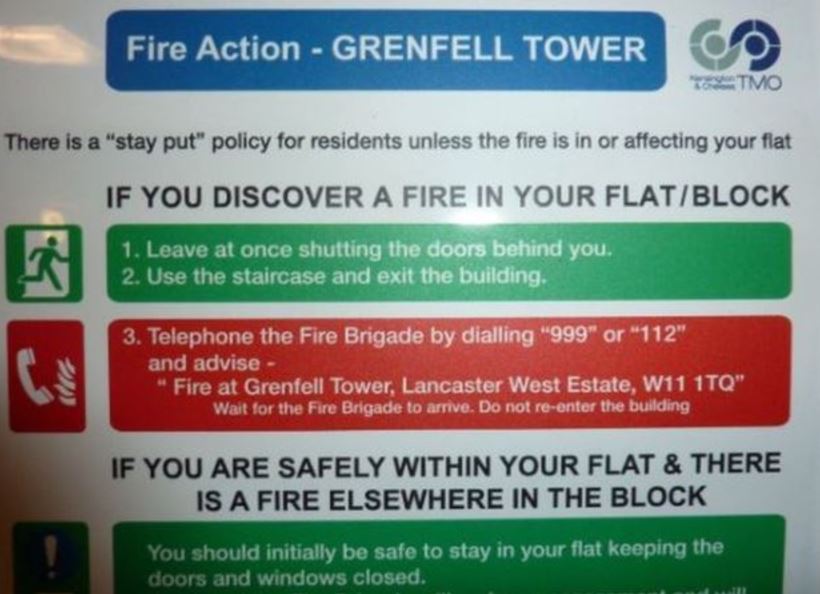

6. Why was the advice to “stay put” given for the first two hours of the fire?

Advice given by the fire service to “stay put” inside Grenfell Tower as the fire spread was only changed after nearly two hours, the BBC has reported.

The policy was only changed at 2:47am, one hour and 53 minutes after the first emergency call.

Based on the ill-founded assumption that the fire can be contained – as it should be if suitable passive fire protection is in place – the advice was potentially fatal to anyone who followed it once the fire had spread rapidly from the room of origin.

With the death toll now estimated at around 80, the ‘stay put’ policy is now under serious scrutiny.

Fire safety notice in Grenfell Tower

7. Why have calls to retrofit 4,000 tower blocks across the country gone unheeded?

Coroners, fire safety professionals and organisations and fire and rescue services have repeatedly urged the government to legislate for the mandatory installation of sprinklers in social housing, over many years.

In February 2013, following a 2010 blaze at a 15-storey block in Southampton, coroner Keith Wiseman recommended to Eric Pickles, then communities and local government secretary, and Sir Ken Knight, then the government’s chief fire and rescue adviser, that sprinklers be fitted to all buildings higher than 30 metres (98 ft).

The following month, Lakanal coroner Judge Frances Kirkham submitted similar recommendation to Pickles.

“In our commitment to be the first government to reduce regulation, we have introduced the one in, two out rule for regulation […] Under that rule, when the Government introduce a regulation, we will identify two existing ones to be removed.” Then housing minister Brandon Lewis rejects calls to force construction companies to fit sprinklers in 2014

In a previous report into the Lakanal House fire, Ken Knight had said that the retrofitting of sprinklers in high-rise blocks was not considered “practical or economically viable”.

However, the evidence Kirkham heard at the inquest prompted her to suggest that doing so “might now be possible at lower cost than had previously been thought to be the case, and with modest disruption to residents”.

This is apparently backed up by a successful retrofit at a Sheffield Tower block in 2012. A report on the installation demonstrated that it is possible to retrofit sprinklers into occupied, high-rise, social housing without evacuating residents and that these installations can be fast-tracked.

8. Are green targets, red tape reduction or austerity to blame?

Inevitably, the media’s focus has varied depending on the political leanings of the publication in question. While the Daily Mail predictably highlighted the prioritisation of green targets as a potential factor, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn even more predictably blamed austerity.

Back in 2015, when the FSF called for a review of Approved Document B, then Conservative MP for Canterbury and Whitstable Julian Brazier said: “My concern is that, at a time when building regulations are more prescriptive than ever on issues like energy saving, the basic requirement to make the building resilient to fire appears to have been lost sight of.”

The fact that Grenfell had just undergone £10m worth of refurbishment to “enhance the energy efficiency of the building” lends credence to these fears.

Artist and writer Akala, however, asserted that “they put panels, pretty panels on the outside so the rich people who lived opposite wouldn’t have to look at a horrendous block.” Whether you agree with this sentiment, that the fire alarms still didn’t work following a £10m refurbishment is appalling.

Another strand picked up was the Conservative Party’s (and to some extent New Labour’s) long-held policy of slashing regulation – or red tape – to boost business.

George Monbiot wrote in the Guardian that: “In 2014, the then housing minister (who is now the immigration minister), Brandon Lewis, rejected calls to force construction companies to fit sprinklers in the homes they built on the following grounds:

“’In our commitment to be the first Government to reduce regulation, we have introduced the one in, two out rule for regulation … Under that rule, when the Government introduce a regulation, we will identify two existing ones to be removed’ […]

“In other words, though he accepted that sprinklers ‘are an effective way of controlling fires and of protecting lives and property’, to oblige builders to introduce them would conflict with the government’s deregulatory agenda. Instead, it would be left to the owners of buildings to decide how best to address the fire risk: ‘Those with responsibility for ensuring fire safety in their businesses, in their homes or as landlords, should and must make informed decisions on how best to manage the risks in their own properties,’ Lewis said.

“This calls to mind the Financial Times journalist Willem Buiter’s famous remark that “self-regulation stands in relation to regulation the way self-importance stands in relation to importance”. Case after case, across all sectors, demonstrates that self-regulation is no substitute for consistent rules laid down, monitored and enforced by government.

“Crucial public protections have long been derided in the billionaire press as “elf ’n’ safety gone mad”. It’s not hard to see how ruthless businesses can cut costs by cutting corners, and how this gives them an advantage over their more scrupulous competitors.”

9. Is the privatisation of fire-safety research a problem?

Stephen Mackenzie, a fire risk consultant who has spoken out on the Grenfell fire regularly in the media, appears to think so. “We’ve increasingly seen over the past decades, our fire research provision within the UK, which is internationally renowned, becoming increasingly privatised,” he told IFSEC Global during a recent interview. “Whether it’s a research establishment which is now a charitable trust, whether it’s a fire service college which is now under the major government support contracts, or the emergency planning college which is under another support service provider…”

10. Why must it take mass casualties to trigger serious change?

It is a fact of human nature that we do not intuit and respond emotionally to risk in an entirely rational way. So it is that 30% of us are, to some extent, nervous about flying, yet few of us worry about hurtling down the motorway at 80mph – despite the fact that you are vastly more likely to die in the latter scenario.

There was no shortage of plane crashes before 9/11, yet none of those crashes had been seared into people’s nightmares. The numbers of people avoiding flying duly soared in the wake of the disaster. This was despite the fact that security was tightened following 9/11, reducing the risk of further attacks.

In his 2008 book Risk: The Science and Politics of Fear, Dan Garder reflected that the thousands of people who eschewed flights in favour of driving in the wake of 9/11 actually increased their risk of dying. “By one estimate, it killed 1,500 people,” he wrote. “On their death certificates, it says they were killed by car crashes. But, really, the ultimate cause of death was misperceived risk.”

Fire disasters of the magnitude of Grenfell are – mercifully – rare. It had been eight years since Lakanal and few remembered it. People were still dying in fires but it rarely made the front pages. Instead, the media was devoting much of its time to the spate of terror attacks and before that, the countless terror attacks that were foiled.

Politicians, believe it or not, suffer from the same askew intuition over risk as ordinary people. Faced with an inbox full of warnings about myriad threats, the Prime Minister inevitably prioritised those that seemed most immediate, most viscerally terrifying and which the media and general public seemed most concerned about.

Fuelled by the decades-long trend of falling fire deaths, fire safety had fallen down the list of priorities. That is certainly no longer the case.

Undoubtedly, so horrific was the Grenfell fire that something will undoubtedly now be done. Whether enough is done, or whether the right things are done, is another matter.

But why must it take a tragedy of such proportions before the problems – which were flagged time and again by fire organisations – are taken seriously? The risk was always there.

While such fires are rare events, any sober analysis would have revealed that Lakanal could readily happen again and that casualties could be far, far worse. And yet it is only when the industry’s worst fears are realised that the momentum for change can truly build.

This article was originally published on SHPOnline sister site, IFSEC Global

An excellent and well researched article – makes a nice change from the usual snippits.

Having read this article I cant help think there is a part missing…. what was happening on the ground. Surely HASAWA places a general duty on the Council to ensure the health safety and welfare of persons within buildings that they own. Now I know before I get shouted at I might be attempting a double bite, perhaps pushing inadequate fire legislation to one side, deliberately so. I would like to know the day to day, week by week, month by month controls that were in place. I do not want to judge the enquiry but stories of no lighting,… Read more »

Brilliant article. I cannot wait to read the answers from the people responsible.