When the most dangerous thing associated with a programme employing 12,000 staff and involving 80 million man hours over five years is a sandcastle, you know you’ve done a good job in terms of health and safety. While the 13 ft-by-6.5 ft sand sculpture on Weymouth beach – built to mark 100 days to go until the Games in April – had to be knocked down for health and safety reasons, the rest of the structures back in east London were standing firm. The London 2012 Olympics continue to be hailed as exemplar – the greenest, the fastest and, perhaps most importantly, the safest.

Over the 80 million hours worked on the big build, there has been an accident frequency rate (AFR) of just 0.15 and the AFR over the last 12 months has been 0.1 – the industry average is 3.4. And for the first time in Olympic construction history there has not been a fatality, a feat recognised last month by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (ROSPA), which presented the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) with an award for completing the big build without a single death.

I hope firms look at our reports and learn from them. I don’t want them to praise us blindly and not apply the lessons

Lawrence Waterman, ODA

These impressive statistics – particularly on a huge scheme spread over a 500-acre site and a five-year time period – are in stark contrast to the industry norm.

A Health and Safety Executive (HSE) report published in January 2012 said that 50 workers were killed in the construction industry over the 12 months from March 2011. This is the highest number of deaths across any industrial sector and an increase from 41 deaths in construction in the previous year.

It’s clear more needs to be done to protect the UK’s construction workers on site, and many are holding the Olympics up as a shining example of what can be achieved.

Lawrence Waterman, Head of Health and Safety at the ODA, said: “I hope this project will contribute to the next generation of development in construction by showing how we can be slicker, leaner and safer.”

Lawrence Waterman, Head of Health and Safety at the ODA, said: “I hope this project will contribute to the next generation of development in construction by showing how we can be slicker, leaner and safer.”

But there are questions over whether this is realistic or whether the “Olympic Effect” drove the impressive health and safety figures rather, than a repeatable system. The Olympics has been in the public eye more than any other scheme in the UK for decades and there have been commitments to be upheld to the government and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) which are likely to have resulted in more attention being paid to health and safety on this project than is usual.

Despite the strong evidence that this increased attention resulted in a glowing health and safety record, the concern is that the time and money might not always be readily given over by clients and contractors on future projects that have tighter budgets and less profile.

“I would hope that companies will look at our reports and actually learn from our success,” says Waterman. “I don’t want people to blindly praise us and not apply the lessons.”

But with the Construction Clients Group (CCG) already in talks with major firms – especially those in the nuclear sector who are most likely to be developing and building on a large scale soon – to ensure the lessons are not lost, the hope is that the Olympic record will live on and make a difference.

Here we consider just how the ODA and its delivery partner CLM ensured that the London 2012 big build was the safest in Olympic history, and whether the rest of the industry is ready to meet the new, high bar that has been set.

Success story

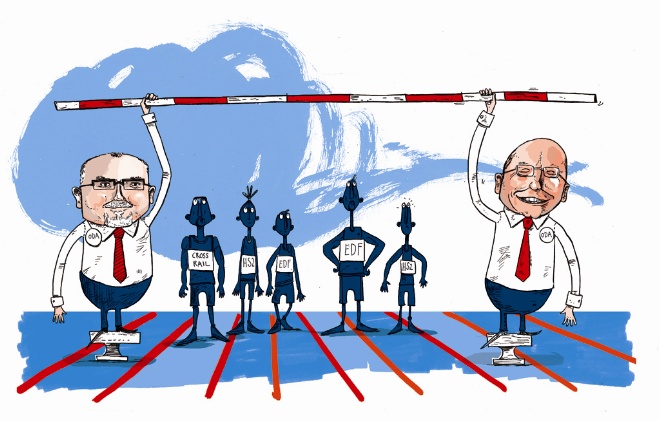

The Olympic big build has topped existing health and safety records. While similarly large schemes such as Heathrow and Crossrail have delivered impressive scores – 0.19 and 0.099 respectively* – the ODA’s efforts are ahead of most and on a par with some of the safest ever projects in the UK.

The trick has been empowering workers and companies involved on the site to, rather than simply dictated to them. Jason Millett, CLM’s CEO and programme director, says: “Right from the outset, the ODA and CLM were clear on what was required out of health and safety. From Sir John Armitt down to the individual firms.

“We met every two-to-three months with the CEOs of our main contractors to talk through any issues or problems so they were shared and discussed to become things we could learn from. At the start, we had a supply chain all at different stages with their health and safety. We wanted to bring them all up to the same level.”

Millett explains that firms were encouraged to develop their own health and safety programmes, but under the umbrella of a park-wide set of standards, overseen by the safety, health, environment leadership team, which he describes as the “glue that held everything else together.”

Any incidents that occurred on site – particularly in the early stages, when people were settling down into their roles – were used as learning points to create a set of common Olympic site standards which were then converted into an image led guide so “it could be easily understood by every member of the 12,000-strong workforce.”

He admits that it wasn’t easy at the start: “Questions were initially raised over whether these park-wide safety standards should be enforced by the client or the developer, or whether it should be outside of standard contractual commitments. But it settled down fast and everyone wanted to work together. We used supervisors as contact points between us and the workforce because we found that any feedback came better from a supervisor than from someone in a suit.”

The success of the Olympic health and safety standards was also founded on research, monitoring and making sure that key trends were spotted. Don Ward, chief executive of the CCG, says one example was a study into the hour of the day when the most incidents occurred on site: “The research found that the most dangerous hour was the one just before lunch,” he says. “Energy levels were waning so mistakes were made. As a result cheap breakfast food, like porridge, was made available to workers to stop this happening and to keep their energy levels up. It was a very simple, but effective solution.”

And Waterman adds that the health and safety figures are a testament to the firms working on site: “everyone was working hard to achieve the standards that had been set. It wasn’t forced. And there was no sweeping under the carpet. A firm would happily say ‘we’ve had a near miss. It would have been much safer if …” and then we would deal with that. And rather than hearing people moan ‘that’s not how we would usually do it’ they would say ‘oh, OK. Let’s try it that way’.”

Learning legacy

The big question is whether the high standards will be remembered – both by the firms who worked on the scheme and by the rest of UK construction – or whether the industry will slip back into poor habits and cutting corners. There is no doubt that the Olympics prove it can be done. But will firms dedicate the necessary time and money to achieve the same standards on projects that are not so much in the public eye?

Atkins’ technical director Martyn Lass says that nothing can detract from the legacy that will be carried on by the workers themselves: “The people are the legacy. And that’s why I think we will absolutely see these standards replicated. Thousands of people have, and will continue to, move onto new projects with a different yardstick having worked on this scheme. They will all have a set of higher expectations of what they want to see on a site and on a project and if they move onto a scheme that’s obviously less safe, they’ll most likely say something.”

Millett adds: “I am absolutely convinced this is repeatable. We have raised the bar but nothing that we have done on the Olympic site has involved reinventing the wheel. Its stuff the industry knows about already. It’s just about an intensified focus. Companies that were working on the scheme have all now left having seen how it can be done. And that will be passed on. “

What worked so well was that it wasn’t about the ODA lecturing us. We were encouraged to take part and get involved

Kevin Underwood, Buckingham Group

And Millett and Lass’ thoughts are echoed by at least some of the contractors involved on the projects. Kevin Underwood is a partner of Buckingham Group, the main contractor on the handball arena. He confirms that his company is a better one for having worked on the Olympics and that the lessons learnt will not be forgotten – especially when it comes to something as important as health and safety: “We have seen how things can be done differently,” he says. “And the huge impact engagement and discussion can have. What worked so well on the Olympics was that it wasn’t about the ODA lecturing us. We were encouraged to take part and get involved.

“A requirement to even work on the park as that each company had a health and safety programme, so that pushed us to roll ours out faster which was a good thing and something we are continuing to focus on.”

Stuart Fraser from Balfour Beatty was project manager on the aquatics centre. He said: “We all shared the good and the bad on this project. All the contractors met regularly and we were encouraged to up levels of engagement. What we have done wasn’t new or different. It was just done well and there is no reason why that can’t be repeated on other construction schemes.”

But there are still stumbling blocks, such as encouraging smaller firms with limited budgets to invest in health and safety, as well as encouraging clients that it is worth the extra money. On the first point, Ward says there is an economy of scale issue. “The issue in my mind doesn’t involve the big contractors on big projects. The Olympics had to deliver to time and budget and accidents slow things down. So there was a real incentive there – as well as being in the public eye – as a significant accident rate would have delayed the programme. But the same principles should apply to every future project over £100m. There is no reason why they shouldn’t.

“It’s the next level down and below where this becomes tougher, where the ownership of health and safety standards might get confused and there might not be enough budget for large scale training and investment. Sometimes you can’t repeat something exactly, but that doesn’t mean you can’t raise the bar by taking elements that worked for you and applying them.”

And Fraser adds that not everything required to raise health and safety standards costs money: “I don’t think the Olympics has set standards that can’t be met by others, even smaller firms. It doesn’t cost anything to engage, talk and communicate. This isn’t about taking on more workers, it’s about having better trained ones to start with.”

On the issue of continued investment from clients, Buckingham Group’s Underwood is not convinced: “On the Olympic Park things were really driven by the ODA and CLM and there was a big investment. I am not seeing other clients necessarily being prepared to invest that sort of time or money for things like directors’ workshops and training sessions. I think so many developers and clients want safe sites and no accidents, but they are not prepared to pay for it.”

He adds that he is hopeful, however, that this will change as more firms roll out health and safety programmes. Plus, there are other moves afoot to ensure that the most is made out of what has been achieved.

The future

CCG’s Ward says that one of the group’s key focuses at the moment is to pass some of the knowledge on to other construction firms and clients, particularly in the nuclear sector: “We are talking a lot to the nuclear sector about what can be learnt from the Olympics in terms of looking after staff to up productivity. It’s about health and safety and also culture – things like onsite healthcare that make the workforce feel safe and respected.

“Nuclear is where the next chunk of work is likely to come from and they need to be aware of the benefits of bringing everyone on side and doing what the Olympics did – getting the workforce to work with you. It is proof it can be done, with exceptional results.”

And Millett adds that, through the Construction Strategy, government is being quizzed on what it is doing to make hitting health and safety targets easier through offering support – especially to smaller contactors. But, he says, the key to a lasting health and safety legacy will be people actively wanting to see it implemented: “Once people have seen the benefits of good health and safety practice, the hope is that they will strive to replicate it. Don’t get me wrong, this hasn’t been an easy process. What we have achieved on the Olympic park took the commitments of tens of hundreds of people, if not more, and there were ups and downs – but it worked. That’s why people in this industry shouldn’t be afraid to watch, learn and make a change.”

HSE: The pressure is on other projects

Philip White, Health and Safety Executive chief inspector on construction, says that the Olympic big build safety success can, and should, be replicated. He will be applying pressure to make sure clients and contractors live up to the new, raised bar.

“The fantastic health and safety results on the Olympic big build have been built on previous major projects such as Heathrow Terminal 5, the Jubilee Line Extension, and Canary Wharf – all projects where a lot has been learnt. And the bar has been raised once again with an exceptionally low accident frequency rate on the project. It shows you can make an inherently dangerous industry safe through a mix of strong leadership and supply chain engagement. This can be repeated on major projects and we are already seeing it happen on Crossrail. And we’ll see the same on nuclear projects and HS2. We [the HSE] will certainly be challenging these clients in the same way we challenged the ODA to hit the highest targets.

“On smaller to medium sized schemes there is a bigger challenge, I admit. But we have published reports following the Olympic big build, including some on how SMEs can learn from the Olympic health and safety strategy. Daily safety briefings, for example, is the sort of thing that can be done whether you have two or 200 people on site. We have another report on safely installing seating in the basketball arena – a small job and one that could be relevant to learn from for smaller firms.”

This article has been published with the kind permission of www.building.co.uk. It first appeared on 01 June 2012 and is available to view here.

*Statistics correct at time of original publication (01 June 2012)

Lawrence Waterman, Head of Health and Safety at the ODA, said: “I hope this project will contribute to the next generation of development in construction by showing how we can be slicker, leaner and safer.”

Lawrence Waterman, Head of Health and Safety at the ODA, said: “I hope this project will contribute to the next generation of development in construction by showing how we can be slicker, leaner and safer.”

[…] Emily Wright looks at how those involved delivered with one of the cleanest records ever – and what lessons can be learnt for the futurehttps://www.shponline.co.uk/47245-2/ […]