Safety performance can reach a point where it levels out and is unable to carry on to the next step. Colm Murphy from Diageo explains the four categories of performance plateau and how to avoid the formation of one.As the term suggests, a performance plateau is the levelling off of performance achievement. For safety this usually means that a reduction in the number of accidents in an organisation has been achieved and sustained but it is unable to go beyond this point and realise the next improvement step, often over multiple years.

Safety performance can reach a point where it levels out and is unable to carry on to the next step. Colm Murphy from Diageo explains the four categories of performance plateau and how to avoid the formation of one.As the term suggests, a performance plateau is the levelling off of performance achievement. For safety this usually means that a reduction in the number of accidents in an organisation has been achieved and sustained but it is unable to go beyond this point and realise the next improvement step, often over multiple years.For many organisations with mature safety systems, the performance plateau is a common challenge. Unfortunately, breakthrough strategies are often ineffective or short-lived. This article outlines the drinks business Diageo’s experience of unbroken safety improvement since 2006 and presents a framework for tackling a safety performance plateau or proactively anticipating and avoiding the formation of one.

In order to effectively respond to the formation of a performance plateau, one must first understand the characteristics of typical plateaux. We present our experience in four categories:

- a positive plateau: one which is sustaining zero or world class safety performance;

- a false plateau: one where the plateau is due to merger and acquisition activities, i.e. new businesses are adding lost time accidents (LTAs) but ‘organic’ improvement is still observed;

- a true plateau: one where performance is levelling off over a sustained period but, unlike a positive plateau, at an undesirable/non-benchmark level; and

- a hidden plateau: one where the primary safety performance measure may be improving but other measures indicate a problem.

Of course, a positive plateau is not an issue unless it drives poor leadership behaviour, complacency or otherwise deprioritises safety. A positive plateau therefore raises the question of sustainability; how can we drive continuous improvement when the primary safety measure (e.g. LTA) already suggests excellence. The best way to address the pitfall of a positive plateau is to change the measure and move to a more supportive performance indicator; for example, many multinational organisations have already moved away from the industry standard ‘LTA rate’ to a total ‘recordable’ incident measure. This provides more data points to measure improvement and the trending of issues for continuous improvement. The use of leading indicators is also beneficial where they drive value-added behaviours and are themselves continuously substituted once a positive plateau emerges.

A false plateau had emerged in Diageo’s global LTA performance in the past two years, driven entirely by acquisitions in developing markets where higher LTA rates have a negative impact on overall performance. Rather than dismissing the plateau as a consequence of acquisition and adjust long-term targets, it is important to use the experience to accelerate performance improvement within the new businesses. Recent Diageo acquisitions have seen a 60 per cent improvement1 in incident rates allowing the business to maintain trajectory to our original 2015 targets.

The hidden plateau highlights the limitations of lost time as a measure of safety performance. To identify and tackle hidden plateaux, safety improvement should be measured across a range of measures. The best example for Diageo was with one of our businesses in emerging markets, which had seen significant LTA improvement in previous years. However, when examining ‘total LTAs’ (including independent contractors), a plateau was obvious.

Such hidden plateaux may manifest in organisations due to a number of factors; perhaps risk has been outsourced rather than mitigated or a myopic key performance indicator (KPI) focus may push resources and leadership priority toward a primary indicator to the detriment of safety for other groups. Understanding the issue more completely allowed our business to intervene and deliver true performance improvement.

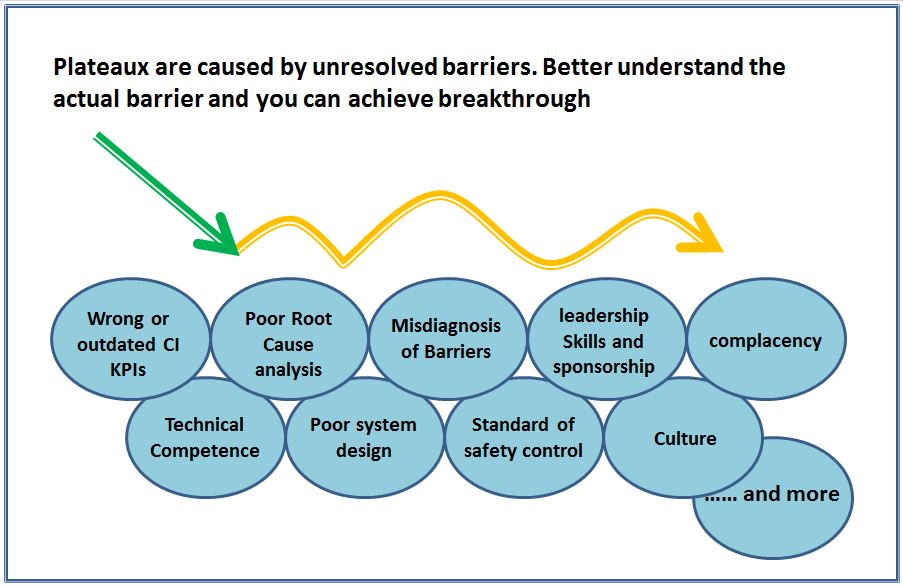

True plateaux are by their nature difficult to understand; they can be driven by a culture of complacency or an organisation reaching a structural capacity (e.g. standard of safety infrastructure) or the limits of leadership and/or technical capability. Performance will, after all, reflect an organisation’s system effectiveness, standard of equipment, layouts, employee capability and engagement levels, leadership sponsorship and safety resource competence.

Unfortunately, it is all too easy to see the emergence of a plateau as confirmation that individual behaviour is at the root of the issue. The problems with such a simplistic assessment are numerous. At the very least, given our understanding of human factors and behavioural science, it is difficult to see behaviour as a root cause in most situations. An understanding of true root cause, ‘just culture’2 and the role of leadership is the only effective means of breaking through the true plateau.

Avoiding the plateau at DiageoIn 2010, the Diageo health and safety leadership team anticipated a global performance plateau within two years. Two thirds of manufacturing sites were already achieving zero LTAs, with 85 per cent of manufacturing sites at one LTA or less performance levels. At these levels, global safety performance was becoming much more vulnerable to single incidents at a site level. The opportunity to drive improvement at a global level with common programmes was narrowing. Site specific interventions focusing on site needs and values were therefore necessary to sustain improvement trajectory.

Early identification of business unit and site-level plateaux were also warning signs of a future corporate level plateau. Global analysis also highlighted the extent of the opportunity; seven sites represented 46 per cent of ‘total’ global LTAs (i.e. including independent on-site contractors). These opportunity sites were subject to increased scrutiny and support with regular leadership level review. These ‘opportunity sites’ delivered almost 50 per cent improvement in the first 12 months of focus.

The Peter Principle

Most people have heard of the Peter Principle,3 which states that people rise in an organisation until they reach their level of incompetence. A humorous cliché in many ways but I contend that it contains a lesson for our profession. Perhaps safety performance improves to the limits of our competence, creativity and influencing skills as professionals and leaders. A difficult challenge for anyone but worthy of consideration in the context of effective continuing professional development.

Although Diageo has developed very successful approaches for avoiding a true plateau to date, the business still has incidents and we remain eager to learn and incorporate best practice from others. Our belief remains resolute that zero harm is achievable.

In closing, I leave you with the following considerations aimed to improve an organisation’s approach to continuous improvement.

Are you measuring the right things to drive continuous improvement?

It is essential to understand the true root cause driving the barriers to continuous improvement.

Cookie cutter or ‘drag and drop’ programmes will only get you so far and can waste considerable resource if not addressing actual problems. All too often we start by discovering a great solution and then go looking for a problem to solve. As safety professionals, we have to be driven by robust analysis and true root cause data.

In mature organisations, corporate level trends and analysis can offer little value to site-level issues.

Consider complacency and lack of insight/innovation as barriers.

References

1.Diageo Sustainability & Responsibility Report 2013 http://srreport2013.diageoreports.com/top-stories/new-acquisitions-achieve-over-60perc-reduction-in-lost-time-accidents-in-just-one-year.aspx

2.Reason, James (1997). Managing the risks of organizational accidents. Aldershot: Ashgate.

3.Peter, Laurence J; Hull, Raymond (1969). The Peter Principle: Why Things Always Go Wrong. New York: William Morrow and Company

Colm Murphy is global safety manager at Diageo

The Safety Conversation Podcast: Listen now!

The Safety Conversation with SHP (previously the Safety and Health Podcast) aims to bring you the latest news, insights and legislation updates in the form of interviews, discussions and panel debates from leading figures within the profession.

Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts, subscribe and join the conversation today!

Safety performance can reach a point where it levels out and is unable to carry on to the next step. Colm Murphy from Diageo explains the four categories of performance plateau and how to avoid the formation of one.

Safety performance can reach a point where it levels out and is unable to carry on to the next step. Colm Murphy from Diageo explains the four categories of performance plateau and how to avoid the formation of one.