Managing process safety risks

“It would have been a brave engineer who spoke up about the potential consequences of a tsunami hitting a nuclear reactor on the coast of Japan.” Trevor Hughes . Giovanni Verlini / IAEA

Trevor Hughes, a risk engineer in Marsh’s Energy Practice in London, examines ways in which process safety differs from workplace safety, with some consequences for the management of high hazard processes.

Equating workplace safety with process safety is a seductive philosophy, with parallels to the idiom “look after the pennies, and the pounds will look after themselves”.

So why is this not a valid conclusion? This article focuses, not on the technical content of process safety management (PSM) implementation, but on the different cognitive challenges of PSM as a possible explanation.

Process safety focuses on the prevention of fires, explosions, and chemical releases that can result in substantial financial loss, multiple fatalities, and long-term damage to the business. By contrast, workplace safety is focused on injuries to employees resulting from accidents such as falls, chemical splashes, or limbs getting trapped in machinery.

In insurance, we consider the potential causes of significant financial loss, and their mitigation. The attention here is focused on process safety issues.

Historically, success in workplace safety was considered a good indicator of process safety. There are sound reasons to view both as interlinked, with their overlaps and common tools. Both workplace safety and process safety require some common features, such as strong operational discipline, clearly demonstrated management commitment, and learning from incidents and near misses.

In the past 20 years, a number of incidents have highlighted that good process safety does not necessarily follow from excellent workplace safety. Some striking examples include the following:

- Exxon Longford (1998) – two workers died in a gas plant explosion. Exxon was considered to have a strong safety management system, well implemented throughout its facilities.

- BP Texas City (2005) and Deepwater Horizon (2010) – 26 fatalities in total. Many with experience of BP would support the view that the company has had excellent commitment and achievement in workplace safety; however, tragically, that performance has not extended to process safety.

- Du Pont Belle Plant (2010) – although the company is admired for its safety culture and practices, a process safety-related incident at this plant resulted in one fatality.

Cognitive differences and their consequences

Process safety is concerned with reducing the risk of low probability, high impact events. By contrast, workplace safety is concerned with reducing the likelihood of lower impact, higher frequency events.

This key difference has consequences in terms of management approach, such as injuries cause pain and emotional impact. As a trailing indicator, employees pay attention to injury performance. An absence of catastrophic events says nothing about their potential. Here, the use of leading indicators is appropriate, but employee impact is less.

Visibility of actions

Good or poor workplace safety is generally visible, at least to organisations and individuals with developed risk awareness skills. Safe and unsafe acts are identifiable during safety observations, audits, and management walkarounds. Observing process safety is difficult since risky behaviour is seldom visible.

Complexity

Process safety situations are generally highly complex; hence distinguishing right from wrong in these situations can be difficult.

Consider a management walkaround where a control room operator is observed acknowledging an alarm. The observer has little opportunity to evaluate and understand whether the operator takes the right action or whether the alarm level is correct.

Even during a formal audit, we have the same problem of complexity. We can audit to see that a process hazard analysis (PHA) has been done; we can even review the methodology. But can we tell if it is a good PHA or a poor one?

Competence

Process safety requires high levels of education, training, and competence to understand complex problems. It also requires soft skills to work in teams with diverse membership.

Diffuse responsibility

PSM can suffer from diffuse responsibility. PSM responsibility is an amalgamation of inputs from design engineers, process engineers, operators, safety specialists, managers, contractors, and construction workers. Safety is seen as a line management responsibility.

However, the line manager may not have the competence, resources, or time to fully integrate the PSM task; hence there is dependence on support departments.

Vulnerability to confirmation bias and groupthink

With “diffuse responsibility” comes a danger of “confirmation bias” and”groupthink”. Confirmation bias is the tendency to interpret ambiguous evidence as supporting an existing position. Groupthink can arise from a desire for harmony or conformity in a group, resulting in an irrational outcome.

Individual creativity, independent thinking, and uniqueness are diminished. Process safety issues are highly dependent on the work of diverse teams of professionals with a desire for projects to be successful; hence the vulnerability to these psychological consequences.

Concern about giving rise to more work and expense

Typically, a PHA will result in the need for additional precautions, instrumentation, and/or equipment. These ultimately incur cost. Initial reaction to such well-meaning recommendations may not be welcoming. A PHA may call into question the basic philosophy of the process.

Speaking out and being heard when fundamentals are being questioned, requires confidence. For example, it would have been a brave engineer who spoke up about the potential consequences of a tsunami hitting a nuclear reactor on the coast of Japan.

Managerial actions to address these consequences process safety performance indicators (PSPIs)

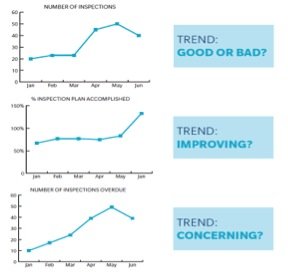

PSPIs can be effective at bringing responsible parties together to drive improvement. PSPIs must be carefully selected to focus where the organisation needs to improve: Good or bad trends should be identified and interpreted early. Consider the following graphs representing inspection activity. The first graph of an increasing number of inspections could be viewed as a good or bad trend. This is clearer in the second graph showing the percentage of plan accomplished. In this hypothetical example, a unit turnaround doubled the number of inspections planned for April/May. At first sight, the trend is improving. In the final graph, the number of overdue inspections reveals a concerning trend.

Communication

More than just promoting the importance of process safety, it is far better is to educate the plant community in understanding PSM basics, goals, and achievements. This would drive plant-wide awareness of major PHA recommendations.

Include process safety considerations in behavioural audit and management walkarounds

Although requiring advance thought and preparation, PSM considerations can form safety conversations, especially in control room situations.

Be prepared to “stop the job”

“Stop the job” is an admirable philosophy, often applied in personal danger situations. “Stop the job” in these circumstances rarely has significant financial considerations. Are you prepared to “stop the job” when process safety issues are at stake? Do your people genuinely display this sort of commitment?

Modify organizational structure

A review of organisational structure may be appropriate; however, there is no “one size fits all solution”. The optimum solution depends on the complexity of PSM challenges for the organisation, its current structure, and the background and competencies of the management. Organisational changes should recognise that PSM can be harmed if responsibilities become too diffuse. Accountability for PSM should be clear, well recognised, and appropriately resourced.

Develop a high reliability culture

The organisation should feel that efforts to identify and highlight process safety issues are valued at all levels of management. Much has been written about high reliability cultures and their key attributes, including, for example, a pre-occupation with avoiding failure, a reluctance to simplify, and respect for expertise. The philosophy of “challenging the green and embracing the red” may not be an easy transition for management.

Single person accountable

Assigning a single person accountable (SPA) is an important step, especially for the management of change issues. The assigned SPA will solicit expertise from those having their own responsibilities. The SPA must gather these contributions and is ultimately responsible for the combined efforts.

The level of the SPA needs to be carefully considered. Too high, and the issue will not get the attention intended; the higher level manager is already surrounded by many other accountabilities. Too low, and the individual may not have the soft and hard skills to fulfil the task.

Assignment of a sponsor for the SPA can help overcome this.

In summary

Good process safety is not a natural consequence of good workplace safety. It requires special attention and additional tools beyond those of workplace safety. However, it does not follow that good process safety can be achieved without a foundation in workplace safety. There are strong common foundations in management commitment, operational discipline, and safety culture.

Trevor Hughes is a risk engineer in Marsh’s Energy Practice in London.

Managing process safety risks

Trevor Hughes, a risk engineer in Marsh’s Energy Practice in London, examines ways in which process safety differs from workplace

Safety & Health Practitioner

SHP - Health and Safety News, Legislation, PPE, CPD and Resources Related Topics

Future-proofing safety: Five trends shaping the PPE landscape of tomorrow

Workers facing uncertain future coupled with health and safety risks, new IOSH report says

Arco backs SHP campaign for PPE inclusivity