The tragic events depicted in the film Everest serve as a reminder of the vulnerability of humans in the pursuit of high achievement. Paul Norton draws on some of the lessons learned.

The tragic events depicted in the film Everest serve as a reminder of the vulnerability of humans in the pursuit of high achievement. Paul Norton draws on some of the lessons learned.

I wasn’t sure what to expect before watching the blockbuster Everest – a $55m production brilliantly shot in IMAX 3D. I didn’t expect a captivating case study in risk management.

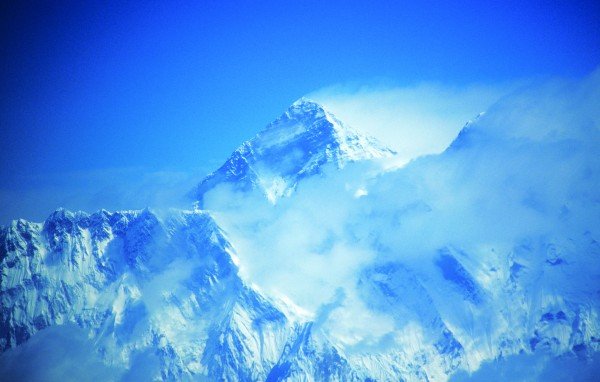

The film recounts the events of 10-11 May 1996 when eight people perished on the world’s highest mountain. A further four people died that year which, excluding recent avalanches in 2014 and 2015, is the biggest annual death toll on the mountain.

Everest has claimed the lives of 282 people since the first summit attempt in 1922. It is thought that the bodies of over 200 still remain on the famous mountain. No other mountain has captured the imagination quite like Everest.

While you can’t really compare the circumstances of Everest with most occupational scenarios, the disaster serves as a powerful reminder of the vulnerability of humans in the pursuit of high achievement and the risks involved. That includes even those at the very top of their game.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be too critical of some decisions made in the ‘death zone’ (above 8,000m) in extreme conditions while deprived of rest, oxygen and nourishment. These decisions played a part in the fate of those that didn’t return home to their families.

This story has been well documented and the subject of many other films, TV documentaries, books and articles. Much contention still exists about the actual circumstances leading to this disaster and the broader commercialisation of Everest expeditions.

The full story is best told by those who left Camp IV for the summit shortly after midnight on 10 May 1996, many of whom have written their own accounts in bestselling books.

What this article does not attempt to do is discuss the many causal factors in detail but instead makes the point that all disasters share common properties and this is no exception. The key parts will always be the role and failures of the people involved, often called the human factors.

At the root is the human desire and motivation to conquer Everest and the risk appetite that is required. Many of the fee-paying clients in this case had no experience of climbing above 8,000m, the altitude at which high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) becomes a significant risk. Supplementary bottled oxygen or ‘O’ was used to mitigate this risk. The use of ‘O’ with commercial guides and sherpas to accompany clients is particular controversial among some climbers. Having those leaders who take care of all path making, navigation, equipment, and make crucial decisions arguably allows otherwise unqualified climbers to attempt to summit in exchange for large fees.

At the best of times there is a limited window of time to summit Everest and return to Camp IV before nightfall. The latest safe summit time from the South Col is 2pm. The expedition encountered serious delays because climbing sherpas had not set fixed ropes as planned at the Balcony (8,350m) and later at Hilary Step (8,760m). The exact cause of this failure is still unknown as sadly both expedition leaders perished. This and the resultant ‘bottleneck’ of 33 climbers caused a delay of some two hours. Three climbers, who were concerned about reducing ‘O’ levels because of the delay, astutely decided to turn back to Camp IV. The rest carried on up. Many did not reach the summit before 2pm as planned.

Scott Fisher (the lead guide from the Mountain Madness expedition) did not summit until 3.45pm. Rob Hall (leader from Adventure Consultants expedition) got to the summit after this while helping client Doug Hansen to summit at his third attempt. Doug was adamant that he wasn’t being turned around again (even with limited ‘O’) and Rob went up with him. Scott, Rob and Doug never made it back to Camp IV.

The extreme blizzard on the late descent reduced visibility, buried fixed ropes and covered the trail back. Early warnings of the approaching storm were given from the control room at base camp but climbers continued to plough on upwards. The competition between individuals and expedition teams and the presence of journalists probably all added pressure to summit. However, the pressure from within to succeed was probably the overriding one, perhaps distorting all perspective.

Away from Everest the whole psychology of accepting known risks as a way of achieving success, reward and achievement continues to fascinate me wherever it may be – either in the workplace or as a sporting and/or recreational pursuit. Balancing risk and reward is the desideratum of risk management. It is certainly the risk that often forms part of the appeal to individuals. It is not necessarily the risk-taking itself that provides the real motive or reward; this is often a means to the end. Ultimately, the rewards come from the expected esteem, satisfaction, gratification, kudos, status and recognition to be gained from the achievement.

Paul Norton is a chartered safety practitioner employed in the sports media sector.

The Safety Conversation Podcast: Listen now!

The Safety Conversation with SHP (previously the Safety and Health Podcast) aims to bring you the latest news, insights and legislation updates in the form of interviews, discussions and panel debates from leading figures within the profession.

Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts, subscribe and join the conversation today!

I’d also recommend watching the documentary film ‘The Summit’ that focusses on a very similar set of circumstances (including late start for the summit, equipment (ropes again) not in place, poor multi-organisational planning, a determineation to carry on regardless…) on K2 in 2008. I watched Everest and The Summit within a week of each other and was amazed with what appeared to be some very basic Safety practices being cast aside. The risk perception of those involved was severly overshadowed by their ‘summit fever’, needing to complete the task beyond all rational decisions. It was also interesting that in both… Read more »