Understanding Behavioural Drivers

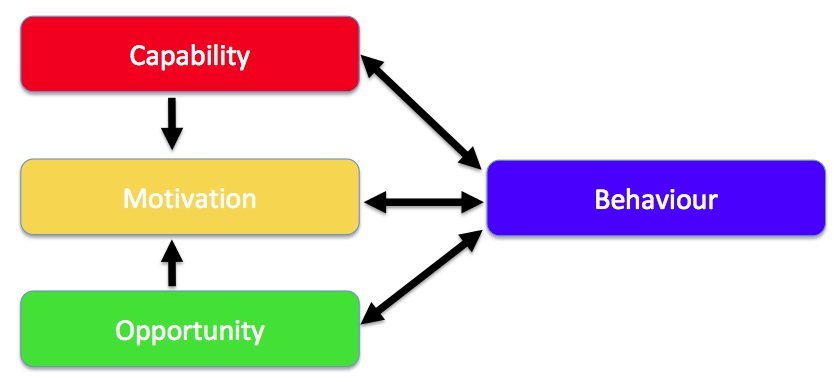

As described in the first article of this series (Safety Behaviour Change), the COM-B (Figure 1) posits that three things are required for a behaviour to take place: the capability (physical and/or psychological); the motivation (both reflective and automatic); and the opportunity (which might be physical and/or social) (Michie et al, 2011).

Figure 1: The COM-B Model (Michie et al , 2011)

Looking at these in more detail, physical capability includes things like having the physical skill, strength or stamina to behave in a certain way. For example, are we fit enough to continue handling well at the end of an eight hour shift? By contrast, psychological capability will include having the knowledge or psychological skills, strength or stamina to engage in the necessary mental processes to behave in a certain way. For example, can we keep all the steps of a vehicle de-coupling process in our heads? Typically, we can intervene to promote capability through training and design. We can ensure that our workers understand and are able to work safely, or at least are able to identify when they cannot work safely (a key component of being a competent person). We’ll cover more on interventions in article four.

Motivation can be a little more tricky to understand and is affected by both capability and opportunity (as indicated by the arrows on the model). Reflective motivation includes processes involving plans (self-conscious intentions) and evaluations (beliefs about what is good and bad). So this aspect of motivation will cover examples such as ’I don’t want to wear my safety glasses because they don’t look cool’ or ‘I intend to take the stairs instead of the lift this week’.

By contrast automatic motivation, as it’s name suggests, does not cover thought through, intentional processes but rather processes involving emotional reactions, desires (wants and needs), impulses, inhibitions, drive states and reflex responses. The uncomfortable feeling that we might be caught doing the wrong thing is an automatic motivator, in the same way that hunger might drive us to take a short cut so we can get to our break early. It also covers the reflex actions we might revert to under pressure – for example reaching for the lever that activates the windscreen wipers on the car we currently drive (say the left hand lever), because it activated the indicators on the car in which we learnt to drive, even though it’s on the right hand side in our current model.

Many safety behaviour programmes focus all their attention on motivation, starting with the assumption that we employ a few bad apples. We seek to identify workers who deliberately take shortcuts or who show a wilful disregard for their own safety or the safety of others. Even approaches such as root cause analysis or the five why’s seem to be about identifying the single reason why an accident happened or a poor behaviour occurred. This approach fails to recognise that motivation is not only multi-factorial, but often lies outside the conscious control of the individual.

Opportunity is the element of this model that resides most obviously outside the individual. The environment in which someone is working affords physical opportunity. This will include time, resources (money, equipment etc.), locations, cues and physical ‘affordance’ (for more on physical affordance see the interaction design foundation). Examples of how physical opportunity can drive behaviour, range from handles on doors being pulled (whether or not that’s the right action) to short-cuts being taken because time is too tight.

Social opportunity describes that which is afforded by interpersonal influences, social cues and cultural norms. These include the influence of our peers, society as a whole as well as our supervisors or managers. These can influence behaviours in positive and negative ways. There are a number of examples in current road safety campaigns, where photos of young children are used on road works signs, alongside a suitable exhortation such as ‘Slow down, my Mum works on this site’.

We have found the presentation of this model to senior teams, line managers and front-line operators has been incredibly powerful given people a way of framing discussions about workplace behaviours and safety; either upstream of issues occurring or following incidents. It helps moves the discussion out of the directly personal and provides a vocabulary to help understand the reality of work (work as lived rather than work as imagined, Hollnagel, 2011). It allows us to move our focus onto the system components other than just the individual and their behaviour – for example to the physical environment; the processes and procedures; the work organisation and supervision; and the raft of priorities with which the individual must deal. It also forces our hand to be participatory and seek out the stories of those ‘in the field’ (Eurocontrol, 2014).

We usually use the simple, three part capability, opportunity and motivation levels, rather than the six part model described above. Unpacking behaviour in this way helps us to avoid the simplistic attribution errors described in the previous article (people behave as they do because they’re ‘bad’ in some way) and encourages us to look at whole system influences on individuals at work.

When we have worked with organisations who adopt a COM-B framework for safety, it promotes richer safety conversations looking at a wider range of factors that might contribute to safe performance. It also helps us design our interventions, which will be the focus of the next article.

Dr Claire Williams is a senior consultant at Human Applications and a Visiting Fellow in Human Factors and Behaviour Change at the University of Derby. She was the Principal Investigator on the IOSH funded project ‘Measuring the impact of behaviour change techniques on break taking behaviour at work’.

Dr Claire Williams is a senior consultant at Human Applications and a Visiting Fellow in Human Factors and Behaviour Change at the University of Derby. She was the Principal Investigator on the IOSH funded project ‘Measuring the impact of behaviour change techniques on break taking behaviour at work’.

In her role at Human Applications she provides consultancy and training to industry and government organisations in behavior change, human factors and risk management.

This blog is the third in a series of four to be published on SHP online. Read the first article on Safety Behaviour Change and the second on Understanding and Identifying Safe Performance.

References for Article 3

Michie, S et al (2011): ‘The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions’, in Implementation Science 2011, 6:42

Hollnagel, E. (2011) Understanding Accidents, or How (Not) to Learn from the Past

The ETTO Principle – Efficiency-Thoroughness Trade-Off Or Why Things That Go Right, Sometimes Go Wrong

Eurocontrol (2014) Systems thinking for safety.

Understanding Behavioural Drivers

As described in the first article of this series (Safety Behaviour Change), the COM-B (Figure 1) posits that three things are

Safety & Health Practitioner

SHP - Health and Safety News, Legislation, PPE, CPD and Resources Related Topics

Workers facing uncertain future coupled with health and safety risks, new IOSH report says

The London Health & Safety Group – over 80 years old and still going strong

New IOSH study centre aims to support Level 6 Diploma