At its heart, health and safety is about the prevention of pain and suffering. Sam Alexander and Chris Lea discuss why laboratory-based scientists should be concerned with the prevention of musculoskeletal injuries just as much as chemical and biological hazards.

One of the main health and safety challenges faced by scientists working in laboratories is the long standing issue of ergonomics; laboratory activities are almost entirely designed to be process-centred as opposed to user-centred. The difference with this type of environment and many others is that the design of equipment is commonly up to 30-40 years old. A microscope is perhaps the best example of this; designed for accuracy and scientific validity, it has advanced considerably since its origin. However, user comfort and adjustability has lagged behind.

High priority, chronic risk

When benchmarking across pharmaceutical industries, it is disappointing to see that more than 60 per cent of reported occupational injuries are musculoskeletal related. [1] UCB is a global biopharmaceutical company focusing on severe diseases in immunology and central nervous systems housing approximately 300 laboratory-based employees. Musculoskeletal risk is one of the high priority, chronic risks UCB is committed to resolving.

We all recognise that ergonomic design and application may not only reduce the number of musculoskeletal injuries but also have very positive effects on the reduction of system or task errors that lead to other types of injury.

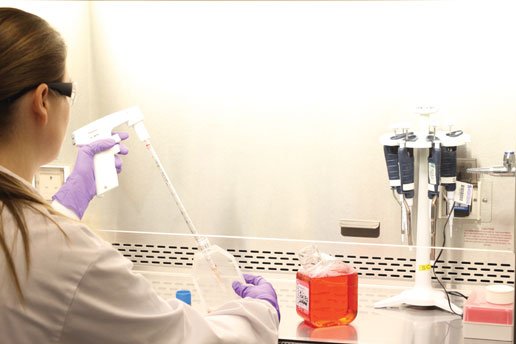

The variety of awkward postures scientists assume within a typical laboratory range from simple lifts, to static postures and miniscule, precise but repeated movements.

Risk descriptors: Laboratory tasks The pinch! Manual activities requiring dexterity and precision often requires a pinch grip, e.g. when handling tweezers and opening vials or chemical bottles. Posture Many tools and instruments encourage bending and twisting of the wrist while working with the elbow held at an elevated position away from the body. Close visual monitoring results in the neck bent forward or to the side. Duration Long static postures, working around equipment e.g. pipetting in safety cabinets or fume hoods. |

Key injury areas are associated with the motion and repetition of the hands, forearm and thumb, or fingers. [2]

Adding to the challenge, design and process changes are subject to regulatory approval for many organisations. This creates some laboratory environments that are very hard to manipulate for multiple users.

In addition, the inherently harmful nature of some materials being handled in laboratory processes demands segregation and protection which must not be compromised for user comfort alone. Ergonomic improvements must balance all risks rather than attempt to order them according to hierarchy.

Just part of the job?

When factoring in the cultural attitudes that were still prevalent, ergonomic hazards and some degree of musculoskeletal injury had widely been accepted as ‘just part of the job’. Changing perceptions and behaviours can be difficult — employees may perceive that changes (to equipment, style or conditions) will result in poor performance, subsequently reducing employee confidence and increasing resistance. Reaching user-centred design has at times seemed a distant dream and subsequently user vigilance for problem points and engagement needed to be nurtured and carefully cultivated.

A summary of what we found at UCB when modelling our results

Good Culture | Have linked MSD to possible work-related cause and reported it. (reacted to symptoms; likely to seek intervention) | Understand MSD symptoms and causes. Strong health belief that it will not happen to them. (failure to identify risks leading to MSD) |

Bad Culture | Have MSD and health beliefs as part of their job. (no reaction to symptoms/ more severe symptoms likely; unlikely to seek intervention) | Have MSD, do not link it to workplace. (no reaction to symptoms/ more severe symptoms likely; unlikely to seek intervention at work) |

| Applied knowledge | Not applied knowledge |

UCB recognised that musculoskeletal disorder (MSD) awareness as a problem was influenced significantly by individual perceptions. Therefore, engagement of employees was the main tool to be used. Health beliefs and cultural behaviours can undermine simple physical adaptations to tasks and activities. It is through continued injury education, leading by example [3], and challenging negative cultural norms, that employees are most likely to adopt better working practices when given the opportunity. This formed the foundation of our strategy.

We began with a strategy of subtle engagement with employees — no announcements, no big posters but instead utilising the classic corridor conversation between an ‘MSD champion’ and employees exposed to laboratory-based musculoskeletal risks. Our ultimate aim is for all employees to be self-aware of MSD, have the ability to risk assess and successfully mitigate the risks and then onward communicate these practices to their colleagues i.e. ‘go viral’!

Strategy summary

1. Address our philosophy

2. Appoint MSD champions

3. Change the risk assessment system

4. Have MSD awareness conversations

5. Hold an MSD forum

A change in philosophy

We knew that very few MSD referrals to our occupational health team were classed as definitively ’caused by work’. We took to changing the philosophy and removed this question altogether. Irrespective of the cause, any MSD may be exacerbated by work, so we felt it was less relevant to consider whether work or home was the source of the problem and shifted the focus to making the person aware of potential causal factors and relevant adjustments that may benefit them.

It was important that the MSD champions were volunteers rather than management-picked to engender trust in the programme.

To find the volunteers we asked our occupational health team to approach employees who had suffered personally with MSD issues as we felt they may be enthusiastic advocates of an MSD programme. It also lent the programme greater credibility to have those that have experienced MSD-related pain, as they could give personal insight into the consequences.

Champions were carefully trained by an external ergonomist on the principles of MSDs. Training was also given by supplier of ergonomic laboratory equipment. The former gave the MSD champion knowledge and credibility, the latter an understanding of industry-specific knowledge and a link to potential innovations that continue to enter the market.

Emotions help to guide risk responses

Much of the training was spent performing movements and understanding the injury outcomes that would be associated with these. To increase the visual content of the training, video footage of common workplace tasks and activities were reviewed to associate movements and injury outcomes with real UCB tasks.

Studies have shown that training that uses high visual and practical involvement increases the vividness of users mental representations of injury and risk [4], the associated emotions help to guide risk responses and may even contribute to conditioning ergonomic behaviours and communications with our MSD champions. Using this approach with the training and then allowing peer-to-peer feedback methods also emphasised the user-centred approach from the outset.

Removing the disproportionate

Our MSD champions became our competent assessors, although expectations were set out clearly that they were not expected to be MSD experts. Our existing risk assessment placed a strong emphasis on lifting and carrying and very little focus on other MSD risks so we designed a simple risk assessment system to identify and filter out risks which could be managed internally and those which a skilled ergonomist would be involved in managing.

Any user-centred task improvement, without proper management carries the potential for users to disappear into a jumble of wish list items. The wish list can be a great place for the skilled ergonomist to start dialogue so that users begin to visualise better ways of working, but a good ergonomist should facilitate a prioritisation process that removes the unreasonably impracticable.

Our ergonomic risk assessments are based on a simple scoring system for three risk areas:

1. Frequency and repetition

2. Force

3. Posture.

Local task or equipment specific information could also be added where needed.

The strategy is that MSD champions undertake the local risk assessments for their department; this allows the assessment to be undertaken by a competent person but also for the local risks (and solutions) to be part of the face-to-face contact.

The ‘conversation’

The ‘conversation’ Following a loose “script” on: MSD facts: MSD symptoms and longevity and impact on home lives and careers. The history and stats for the UK and also UCB MSD cases. UCB changing strategy and proactive approach. MSD primary risks High repetition (high = less than 30 seconds of movement repetition) Forceful exertions (heavy loads/ forces on limbs, fingers, etc) Awkward postures (away from the neutral position) Local risks Taking the key points from the department risk assessments that are local and discovered by the MSD Champion and their solutions. Feedback Feedback from the ‘contact’ to the MSD forum. |

This part is relatively simple; the champions have a list of laboratory-based employees and will engage in a one to one for both newcomers (as part of a mandatory induction) and existing lab-based colleagues (subtly as part of day-to-day dialogue).

Using recognised and tested ergonomic principles with employees reduces the risk of unnecessary costs though poor interventions, cementing the idea that there is a high level of ownership of the problems and the solutions.

Care must be taken when engaging and empowering groups so as not to create a situation where groups feel ‘out on a limb’ (pardon the pun), the aim is to create a degree of self-sufficiency with easy access to skilled support and advice as where they need it, with this in mind the intended approach was less ‘bold stroke’ and more ‘long march’.[5]

Finally, we created a governance team just for MSDs as part of the overall company HS&E strategy. It gives entire credence to the strategy and the adoption of the recommendations from the MSD champions. Identifying existing organisational routes for information sharing and utilising these for the initiative ensures that a learning legacy is grown and shared so that the organisational memory is nourished and, in time, perpetuates user-driven solutions based on sound evidence from within the business.

The forum provides a platform for further dialogue and understanding of the factors that perpetuate the musculoskeletal risk behaviours (tools, design, organisational factors or cultural and personal behaviours) [6]. Inevitably the more dialogue and better the understanding, the greater the quality and effectiveness of solutions.

With any injury prevention strategy and the associated communications, there are a number of success factors at play. Ideally, we want all our colleagues to have the means and tools to reduce risks for themselves, the opportunity to execute adjustments and communicate their successes to the organisation.

In future audits, indicators of the early signs of improving awareness and changing health beliefs as employees acknowledge ‘it could be me’, should begin to materialise.

Current status

This strategy is not likely to see the numbers of MSD referrals reduce immediately and it would be arrogant to assume that all injuries would be prevented with the introduction of the MSD champions and access to ergonomic improvements. We actually expect an increase in numbers of employees seeking early intervention for self-reported MSD symptoms to rise (due to the awareness).

Broadly speaking we expect this to be a 36-month plan of continued awareness conversations refreshed with different risk topics (as determined by the MSD forum). We are also becoming more aware of suppliers of laboratory equipment that are now exploring and marketing improved ergonomic equipment. Holding a musculoskeletal ehibition for proactive equipment suppliers to show their equipment is to be undertaken in the near future.

Culturally, we have a long way to go in breaking down the reservations about seeking help so the campaign also sought to remove barriers to rehabilitation. However, through this strategy assistance is more likely to be sought early and the severity of the injury can be limited — we believe we are on the right road to tackling the HSE stats for the pharmaceutical industry.

References

1. HSE source http://www.hse.gov.uk/pharmaceuticals/

2. G. David, P. Buckle, “A questionnaire survey of the ergonomic problems associated with

pipettes and their usage with specific reference to work-related upper limb disorders,” Applied

Ergonomics, 28(4):257-62, 1997.

3. Health and Safety Executive. Reducing error and influencing behaviour (HSG48).HSE Books, 2003.

4. Risk As Feelings, Lowenstein, G.F. Psychol Bull. 2001 Mar;127(2):267-86.

5. Kanter RM,Stein, BA and Jick TD (1992)The Challenge of Organisational Change: How companies experience it and leaders guide it. New York: Free Press

6. Sulzer-Azaroff B. The modification of occupational safety behaviour. Journal of Occupational Accidents 1987; 9: 177—197.

Sam Alexander is director of AM Health & Safety and Chris Lea is senior group leader for HS&E at UCB

This article was original published in March 2014 in SHP Magazine.

What makes us susceptible to burnout?

In this episode of the Safety & Health Podcast, ‘Burnout, stress and being human’, Heather Beach is joined by Stacy Thomson to discuss burnout, perfectionism and how to deal with burnout as an individual, as management and as an organisation.

We provide an insight on how to tackle burnout and why mental health is such a taboo subject, particularly in the workplace.

Just a shame industry managed to block ratification of 2012 EU MSD Directive ……