Workers In Coal Fired Power Station

Jerome Hart, market leader UK for DuPont Sustainable Solutions explains the psychology behind so-called “intuitive” decisions that affect work safety.

Faced with a critical, complex situation that requires a split-second reaction, how likely is it that two people will make the same decision?

This is a situation many industrial companies have to plan for. Their employees do not work in a consistent, unchanging environment performing entirely predictable tasks at all times. Nor do they always make rational decisions or even the same ones under the same conditions.

As technical barriers to accidents and safety guidelines are only as effective as the people who use them, industry must therefore be prepared for employees to not always make the right, safe decision when installing, operating or maintaining equipment and has to know how to counteract that.

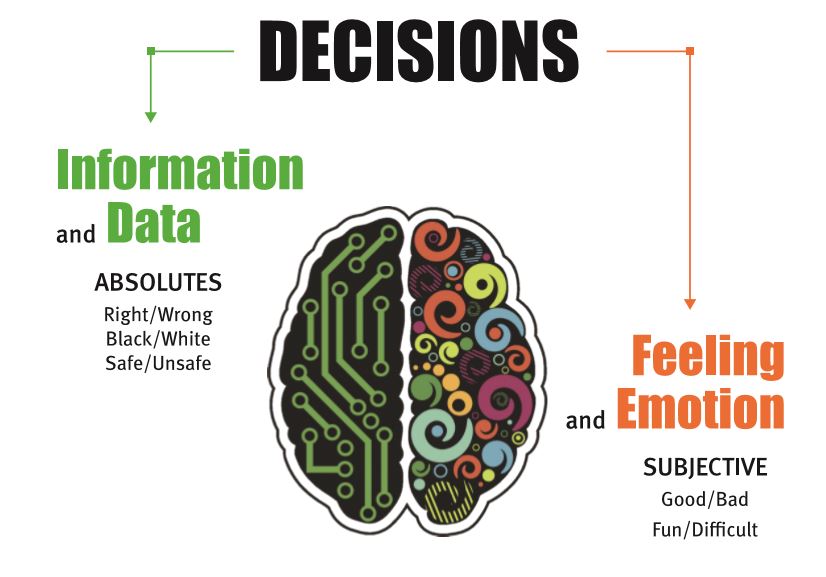

The decisions people make are not always based on information and data, but are influenced by feelings and emotions (Figure 1). Their responses to situations can therefore vary widely.

Figure 1

In order to manage circumstances that are outside of standardised processes, DuPont believes it is important to move beyond mere behaviour-based safety management and to consider how decisions are selected and acted upon.

We have therefore developed an approach to safety that uses neuroscience and affective psychology. This links decision-making, conscious and sub-conscious functioning and affective behaviour, in other words behaviour determined by feelings and emotions.

Chance variability of judgments

As Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, and co-authors Andrew M. Rosenfield, Linnea Ghandhi and Tom Blaser pointed out in the October 2016 issue of the Harvard Business Review (HBR) , inconsistent decision making has a high cost for businesses.

This is particularly serious when those decisions affect safety. Recognised for his work on cognitive biases Kahneman and his co-authors draw attention to the fact that people’s “judgments are strongly influenced by irrelevant factors, such as their current mood, the time since their last meal, and the weather. We call the chance variability of judgments noise. It is an invisible tax on the bottom line of many companies.”

In the article Kahneman et al explain the difference between two types of influences on judgment and decision making. They distinguish between social and cognitive biases, and noise.

We are all familiar with social biases such as racial prejudices, but perhaps less so with cognitive biases. These are biases formed by our experiences, perceptions and emotions, and they can prompt us to take mental shortcuts. Some of the cognitive biases that are most relevant to industrial safety management are:

- the availability bias – overestimating the value of information that is readily available. If you witness someone trapping their hand in a machine, you are more likely to overestimate the risk of that happening to you than someone who hasn’t recently witnessed the incident. The same also applies in reverse. If you have seen someone take a risk and get away with it, you are likely to assume you can take the same risk and stay safe.

- the outcome bias – a focus on the outcome rather than on the decisions that led to it. For example, if you can quickly clean equipment without locking out and have not had any accidents doing so, the perceived risk of that decision and action is low.

- the bandwagon effect – if an influential person in a group expresses a certain opinion about a risk involved in a certain activity, the number of people in that group holding that belief is likely to increase.

Kahneman and his team explain that many errors arise from a combination of bias and noise. Accurate decision making is influenced by neither. However, when bias is present, decision making is likely to be off target even if it falls within similar parameters every time.

Moving beyond behaviour-based safety

So how can companies mitigate the influence of noise and biases on safe and consistent decision-making by employees?

Risk management strategies have long used psychology to study, understand and influence the behaviour of employees. As professionals in safety, we have worked with companies around the world in a wide range of industries and have seen what changes a consistent behaviour-based approach to safety and an integrated process safety management system can achieve.

However, behavioural safety has its limitations. Perhaps that is why statistics by the HSE show many UK companies to be reaching a plateau in safety performance.

In the organisation’s latest statistical report the HSE recorded, “There has been a long-term downward trend in the rate of fatal injury, although in recent years this shows signs of levelling off.”

One solution Kahneman proposes is to “adopt procedures that promote consistency by ensuring employees in the same role use similar methods to seek information, integrate it into a view of the case, and translate that view into a decision”.

He suggests that “professionals should be offered user-friendly tools, such as checklists and carefully formulated questions, to guide them as they collect information (…)”.

Using the risk – reward balance to increase safety

People almost instinctively balance risk versus reward when making decisions. Given our past experiences, most of us tend to underestimate risks and overestimate the reward. That often leads to the wrong, unsafe decision.

In a work environment, perceived rewards are everywhere.

- Production pressure will lead to a perceived reward. If you can quickly fix something without locking out, you can continue producing. When you save time, you can also continue with your next task, or take a break, or go home earlier.

- Being embarrassed, or not wanting to disappoint your shift or leader – because it will be your shift who was not able to complete the task.

- Your personal passion is a strong emotional reward. Typically, maintenance mechanics love fixing things. That’s why they are in maintenance. Waiting for the work permit to be signed, for the equipment to be locked out, for the right oil, etc. does not offer a reward.

- Social connectivity is also a powerful emotional reward – why do we text/phone when driving?

DuPont has been looking at how we can change environments to prompt correct choices for some time. There are several methodologies to support organisations.

One is the Nudge Theory: a simple example of a nudge is a walkway in a factory, with feet painted on it to nudge people to use it as a path. A colour coded lock-out situation will nudge people to connect the lock to the right lock out point.

Another approach is what we call ‘Lean Thinking in the area of risk and safety’. This looks at the flow of operations or activities from a risk/reward perspective. If a walkway results in a 10-minute detour several times a day, the perceived reward of taking a shortcut is very high, versus the risk of not using the walkway. The idea is to improve workflow so that people are not tempted to take shortcuts.

Automated behaviour starts with a cue. Routines trigger behaviours and perceived rewards. To change a habit, we need to change the cue, the perceived reward, forming and maintaining new habits through repetition and reinforcement.

The new operational risk approach

DuPont now focuses on building capabilities that engage people at an emotional level and influence their intuitive decision-making, first acknowledging and then eliminating noise and neutralising biases.

We do so by making people more aware and conscious of their biases so they can anticipate potential risk-based decisions and can take preventative action.

We use assessments, behavioural interview techniques, check lists and focus group discussions, and also make sure senior leaders and supervisors understand their critical role in shaping the decision-making process of their staff.

Working with customers across a variety of industries around the world, we have proved that this approach works effectively even for a widely distributed workforce.

If organisations do not understand how decisions are made by the different people that make up their workforce, they are unlikely to be able to achieve sustainable safety improvements.

They need to know how workers will react in scenarios that fall outside normal rules, procedures and predictable environments.

Will they let their subconscious decision-making take over or will affective risk management psychology and training kick in, so that even unexpected risks are met by deliberate, conscious actions?

Jerome Hart is market leader UK for DuPont Sustainable Solutions

To find out more about risk mitigation in decision-making, click here.

The Safety Conversation Podcast: Listen now!

The Safety Conversation with SHP (previously the Safety and Health Podcast) aims to bring you the latest news, insights and legislation updates in the form of interviews, discussions and panel debates from leading figures within the profession.

Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts, subscribe and join the conversation today!